GEORGIA

Georgia...Georgia...the whole day through

Just an old, sweet song keeps Georgia on my mind.

—Ray Charles, Georgia On My Mind

The devil went down to Georgia,

He was looking for a soul to steal.

—Charlie Daniels, The Devil Went Down to Georgia

The Heart of the South

We see cotton plantations, hear thick, drawling accents, and think of hot, humid summer days and nights and people who are accustomed to them. Georgia is the Gone With the Wind state. It’s the deep South, conveying images of peaches, peanuts, mint juleps, and the wide, winding staircase at Tara. Images of the Civil War are in general dirty, ugly, bloody and depressing, which is as it should be. But thanks to Margaret Mitchell and David O. Selznick we also have images of the Civil War in Georgia as a romantic drama, a majestic, epic adventure of human tragedy and triumph.

While the state of Georgia may be quintessentially southern, it also seems the most cosmopolitan of the southern states, due mainly to its largest city, Atlanta. When we’re not thinking of Atlanta burning, or Vivien Leigh walking through it as she tends to hundreds of wounded soldiers, we think of Atlanta with high-rises, the nation’s busiest International airport, the Braves’ baseball team, and CNN.

There is also, of course, another Georgia —the one in Eastern Europe. The Republic of Georgia is situated in between the Black and Caspian Seas, bordered on the south by Turkey and Armenia, on the west by Azerbaijan, and on the north by Russia. This Georgia, which has been so called since at least the 5th century A.D., is said to have taken its name from either Saint George, a martyr who is said to have been killed three times, only to be brought back to life each time by the power of God, or from the Greek word georgos which means “tiller of the soil.” The state, on the other hand, was definitely named for a British monarch.

The country of Georgia is about half the size of the American state but has approximately the same population. Interestingly, the Republic of Georgia straddles the Caucasus Mountains, from whence we get the name of the Caucasian race. This word, while technically referring to a tribe originating from this relatively small region, has historically come to refer to the entire world population of white-skinned people. How ironic, then, that the U.S. state of the same name is home to the largest U.S. population of African-Americans, which is to say black-skinned people, in the nation.

Guale and Mocama

Georgia was the last of the twelve original colonies to be formed by England and populated by immigrants coming directly from Europe. Chartered in 1732, one hundred and twenty-six years after the first charter of Virginia, the region that we now call Georgia had actually flirted with European colonization long before Jamestown was founded in 1608. But not by the English. In the late 1500s the French and Spanish were clashing on the coast of La Florida as far north as current South Carolina. By 1606 Spanish missionaries had built a series of missions on the coastal islands of Georgia with names more reminiscent of the coast of California than that of Georgia: Santa Catalina, San Buenaventura, San Jose, and San Pedro.

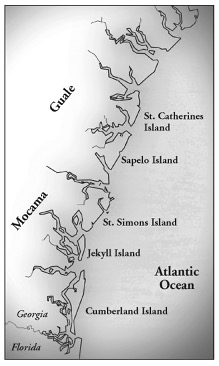

The Georgia coast was roughly divided into two districts by the Spanish. The northern section was called Guale , pronounced “WA-lee,” a name which was taken from the island the Spanish labeled Santa Catalina —Guale was the name of the most powerful chief on the island, and the Spanish also used it to refer to the tribe. The southern coast of Georgia was called by the Spanish Mocama after the dialect spoken by those natives.

In 1597 a disastrous uprising that resulted in the destruction of the missions, took the lives of several Franciscan missionaries in the Guale and Mocama districts. The revolt was termed the Juanillo uprising after its rebellious Indian leader. Spain retaliated by destroying native villages, and years of attacks and reprisals followed. Juanillo was eventually killed, and the Spanish authorities felt they had their revenge. They rebuilt, to some extent, the missions of the region, but this never led to Spanish colonization, and the region remained a contested but unsettled zone between the Spanish stronghold of St. Augustine in La Florida and the new English colony of Virginia.

Azilia and Georgina

In 1663 King Charles II created the colony of Carolina just south of Virginia. Initially the borders of the new colony were relatively modest, but two years later they were expanded. Now the southern border of Carolina, by the English definition, engulfed St. Augustine in La Florida. The Spanish were understandably alarmed, but the land was still unsettled, and while tensions mounted there were no open hostilities between the two colonies. In 1670 Charles Town (Charleston) was founded in southern Carolina and quickly began to flourish. Now the issue of settling the lands to the south in order to provide protection for Charles Town against both the Spanish and the Indians grew far more important.

Ideas for a separate colony began in earnest around 1700. Carolinians wanted a colony of “farmer-soldiers” who could both make a profit on the land and serve as protection for themselves. Needless to say, while land grants for colonization were coveted, the conditions and the region available were not considered prime, and technically the land was under the ownership and control of the Carolina proprietors (see North and South Carolina ). Still, there were interested parties.

The first person to offer a solution was a Scottish baron named Sir Robert Montgomery. In 1717 he proposed the establishment of a colony with himself as governor, but allowing the Carolina proprietors to keep their property rights. Montgomery wanted only the title of governor-for-life and the chance to engage colonists in cultivating silk, wine, olives, raisins, almonds and currants. Montgomery painted quite a rosy picture of the prospects for this new English colony, one which he would call the Margravate of Azilia .

A margravate is, by definition, a border colony or county, military in nature. The word is of German derivation, describing the lands held by a margrave, or nobleman in medieval Germany, who was appointed the task of defending his homeland’s borders. Azilia has been called both “a fanciful name of unknown origin” and “a Mesolithic European culture.” (While the real definition is elusive, the word is used today as a popular Internet directory.) Montgomery’s plans for Azilia were detailed but perhaps a bit too ambitious. Neither he nor the Carolina proprietors could afford the scheme, and the three-year time limit on the establishment of Azilia expired.

Another proposal, made by Jean Pierre Purry in 1724, also failed for lack of financing. A Swiss wine merchant, Purry hoped to develop exactly what the Carolinians wanted—a colony of Swiss farmers who would also act as soldiers to protect the border. He proposed the name Georgina in honor of George I, the Hanoverian King of England. While Georgina never materialized, Purry did succeed in establishing a small settlement in modern South Carolina, which he called Purrysburg. This colony eventually failed and disappeared from the map, but Purry is forever credited with his enthusiastic advertising of Carolina in his homeland of Switzerland, instigating what would become known as "Rabies Carolinae" or “Carolina Fever.”

The colony of Georgia would be created within the next decade, and would serve a purpose very different from those of these initial attempts.

Oglethorpe

The undisputed founder of Georgia was James Edward Oglethorpe, though under closer inspection the idea for the colony may have originated with any of a number of Oglethorpe’s colleagues. A member of the House of Commons, Oglethorpe had from 1724 led a fairly undistinguished parliamentary career. But he was moved to action when a dear friend, Robert Castell, died in 1728 in Fleet prison where he had been incarcerated as a debtor. Oglethorpe succeeded in instigating an investigation which led to the prosecution of some of the worst prison wardens, but that wasn’t enough for Oglethorpe. Working with a philanthropist named Dr. Thomas Bray, he and several associates applied for, and were granted, a colonial charter in 1732 which would be charitable in nature. The idea was to create a place where debtors could be sent, rather than to prison, in the hopes of starting a new life.

The history of this charter and of Oglethorpe’s motivations has led to an extremely defensive posture by many Georgia historians. The reputation of the colony as one that was begun by prisoners—thieves, murderers, etc.—has led author after author to deny the allegation unequivocally. They are, in fact, correct in their denials. By the time the charter was granted and colonization began, the focus had indeed changed somewhat. No longer would this be a place for incarcerated debtors; instead it would be home to the “deserving poor.” The colony’s Trustees chose carefully the first group of settlers who sailed for Georgia in November 1732, and there is no evidence (though evidence has indeed been sought) that there were any convicts among them.

Oglethorpe named his colony for his King. Britain was ruled by four Georges from 1714 to 1830, all known for their Hanoverian origins and for their seemingly hereditary penchant for passionately hating their respective fathers. The George that Georgia was named for was King George II who reigned from 1727 to 1760.

An accomplished soldier, George II was the last British monarch to lead troops into battle and later survived a threat to his power by Bonnie Prince Charlie, the last of the Stuarts to attempt to reclaim the British throne. George II’s eldest son Frederick (with whom he shared a mutual contempt) died without ever assuming the throne, and so in 1760 the monarchy passed to Frederick’s son, George III, perhaps the most famous of the Georges and the one who ruled the longest.

Pushing Southward

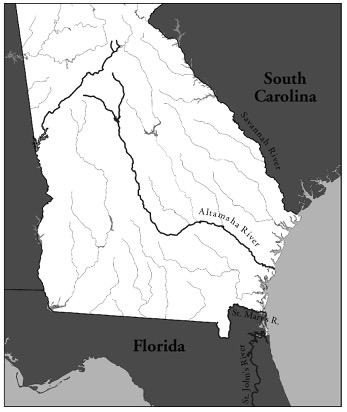

While Georgia’s northern border was, from the colony’s birth, the Savannah River, her southern border was always vague and changing and would not be firmly settled until after the American Revolution. By the time the colony’s initial charter was granted South Carolina had divided from the north, and become a Royal province under the control of the monarchy and no longer answerable to its now defunct proprietors. This made it easier for the king to determine borders and to simply slice off a chunk of South Carolina, call it Georgia , and bestow it on Oglethorpe. The original southern border of Georgia was the Altamaha River, though that limitation was virtually ignored by early Georgians who eagerly moved south, establishing trade with the Creek Indians and further threatening the Spanish in Florida.

In 1763, after the French and Indian War, East Florida was ceded to England, making Georgia’s southern boundary an internal government matter rather than an international one. The southern border of Georgia was placed at the St. John’s River near present-day Jacksonville, but after complaints from the new English governor of East Florida, it was moved north to the St. Mary’s River. Like virtually all of the other English colonies, Georgia’s western border extended all the way to the Mississippi River, even though King George III had forbidden trans-Appalachian settlement by a 1763 decree.

Georgia’s delegates to theContinental Congress in 1776 were eager signers of the Declaration of Independence. After the American Revolution, which saw some of its most brutal guerilla fighting in the three southernmost colonies, Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the Constitution, which it did on January 2, 1788. Four years later the state ceded her western lands to the federal government, firmly fixing her western border. Once and for all her borders were firmly settled.