SOUTH CAROLINA

“Just a little bit south of North Carolina

That’s where I long to be

In a little brown shack in South Carolina

Someone waits for me.”

—Dean Martin,

Just a Little Bit South of North Carolina

“From South Carolina

To San Francisco

I’m always waiting here

Outside of this door”

—Her Space Holiday, From South Carolina

SOUTH Carolina

Of all of the “southern” states the only one that contains the word “south” in its name is the smallest of them all, South Carolina. The word “south,” in our historical and geographical lexicon, is almost synonymous with the Civil War, slavery, Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement. “South” signifies the struggle of black people in America to overcome oppression, a battle that climaxed with the Civil War...which started in South Carolina.

While South Carolina does not have a monopoly on retaining its southern flavor, it does seem that a few southern states have tried hard to slough off their relationship to the Civil War era, to leave behind their connections to slavery and to the bitter conflict which that peculiar institution provoked. But South Carolina may never do so, nor may it ever want to. South Carolina uses its connection to the history of “The South” to frame its own reputation.

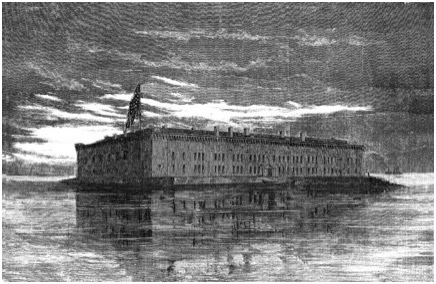

Of course, South Carolina’s relationship to the Civil War is not just philosophical or ethereal. It is tangible. It is full of dates, places and people—real history. On April 12, 1861 Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was seized by Confederate troops, marking the beginning of the Civil War. Sherman’s famous march to the sea burned a swath through South Carolina that branded it with the brutality of the war for posterity. And in the late 20th century the confederate flag took center stage in a controversy over whether its presence flying over the South Carolina statehouse was appropriate.

Writing in late 2009, the name South Carolina conveys other meanings besides its connections to southern heritage. In particular, those who follow politics closely are aware of the sordid scandals that seem to be plaguing the state’s politicians. First, Governor Mark Sanford gave new meaning (to the delight of late-night talk-show hosts) to the phrase “hiking the Old Appalachian Trail.” And as if the sex scandals are not enough, in the Fall of 2009 South Carolina Representative Joe Wilson was reprimanded by the U.S. House of Representatives for shouting “You lie!” at President Barack Obama, interrupting a speech to a joint session of Congress. For some, of course, Joe Wilson’s actions—rather than being a scandal—were simply another display of the state’s natural tendency to rebellion.

But besides a few unfortunate news stories, and besides its renown as a still-rebellious southern state, South Carolina is also distinguished by a famous native son, beloved by many late-night faux-news fans. Steven Colbert, talk-show host extraordinaire, has created such a perfectly sardonic persona, that his personal politics are the subject of dinner-table debate nationwide. Leave it to South Carolina to produce such an enigmatic-yet-still-lovable character.

King Charles II

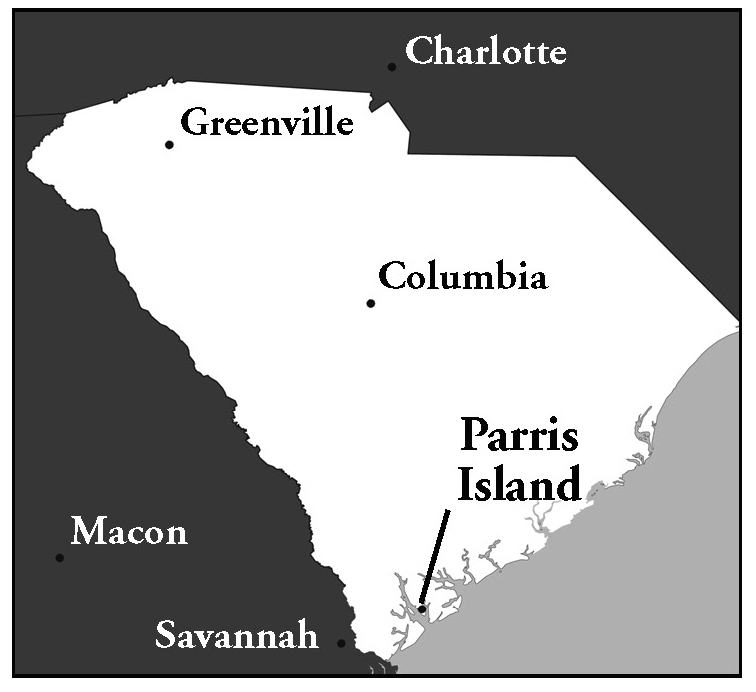

In 1566 the Spanish built a fort on Parris Island off the coast of what is now South Carolina. They named it, and the settlement that grew up around it, Santa Elena, and for twenty years it was the Spanish capital of La Florida. The settlers endured constant clashes with local natives, and in 1576 the fort was actually destroyed and rebuilt. With the encroachment of the English on the eastern seaboard, Spain finally abandoned Santa Elena in 1587 and moved their capital down the coast to St. Augustine.

For the next eight decades, the area of South Carolina saw no attempts at settlement by Europeans, but that changed when the Virginians began to push southward. Because South Carolina shares an intimate history, not to mention a name, with its northern neighbor, a lot of information about the name “Carolina” is contained in the chapter on North Carolina. But briefly, the name Carolina was bestowed on the colony by King Charles II in 1663, and he named it in honor of himself. Carolina is the feminine form of the Latin Caroluus. The word has its origins in the Germanic languages as “Churl” which referred to a common man, specifically not royalty. The name gained a higher status with the success and fame of Charlemagne, and became appropriate for naming princes and kings. When those kings then used their own name for land that they claimed, it was generally converted to the Latin feminine (as in Louisiana and America).

The use of the name by Charles II was not merely a matter of ego. King Charles, the rightful heir to the English throne, had been living in exile since his father’s execution in 1649. Many of his loyal subjects had worked tirelessly for years to see that the king was eventually restored to the throne in 1660 after the death of Oliver Cromwell and the weakening of Parliament. The eight people to whom he granted Carolina were among those who had given him back his kingdom, and this was his way of rewarding them.

But the eight proprietors were mostly absentee landlords (with the exception of William Berkeley, governor of Virginia) and had much difficulty colonizing their new province, especially in its southern region. It was almost immediately clear that the colony was too massive for one governor to manage, and until about 1670, when Charleston was firmly established (an earlier settlement at Charleston−or Charles Town−had failed in 1667 because of lack of support from England and troubles with the local natives) the northern section of Carolina−the region just south of the Virginia border−was the only European-populated area.

The Barbados Connection

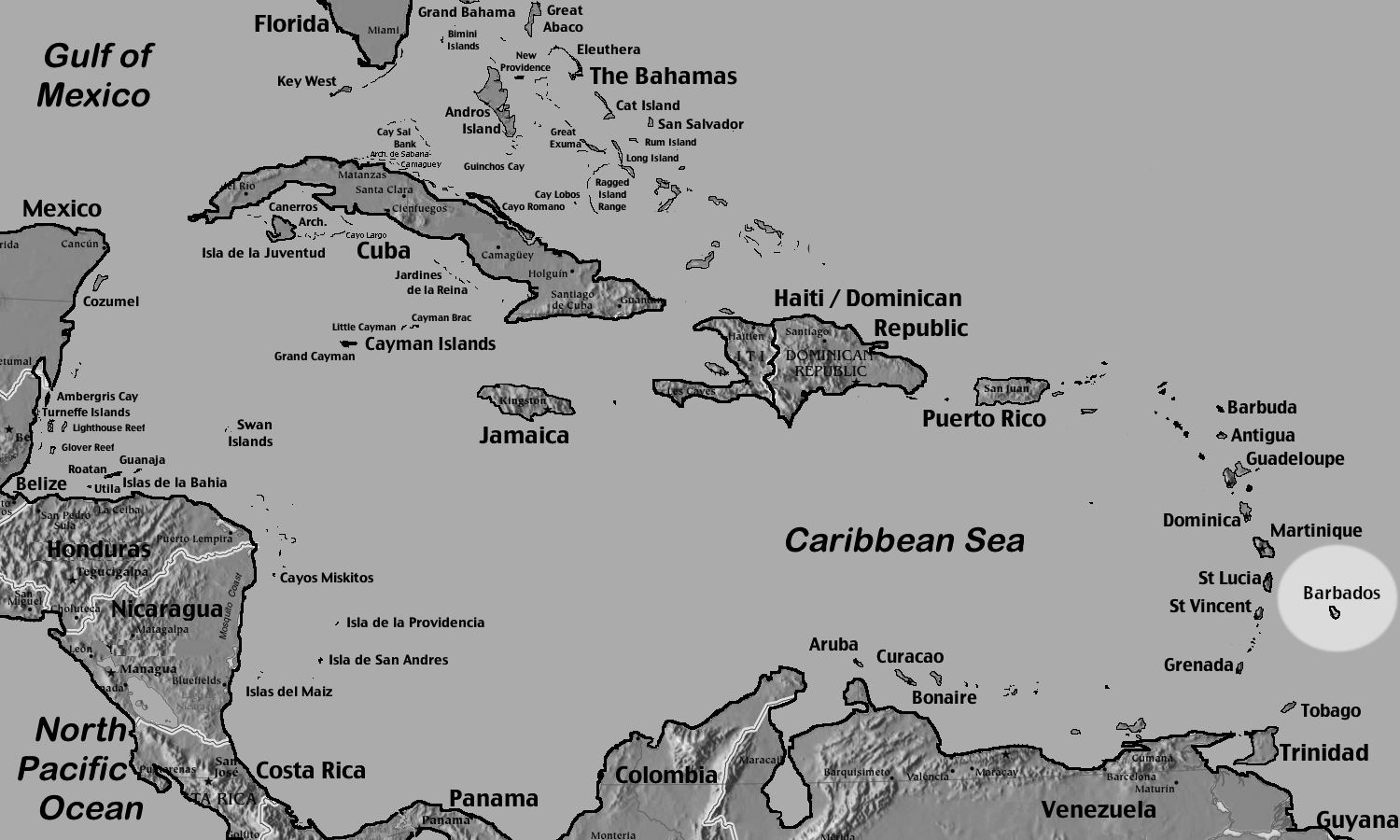

The island of Barbados in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies was England’s stronghold in the Caribbean Sea. Settled in 1627, it began to flourish with the introduction of sugar cane as a cash crop in the 1640s. Large plantations worked by African slaves coupled with a worldwide demand for sugar, rum and molasses made a handful of Englishmen massively wealthy.

One such man was Anthony Ashley Cooper, first Earl of Shaftesbury, and one of the eight proprietors of Carolina. Ashley convinced the proprietors to finance a colony of settlers who would be primarily immigrants from Barbados, and would export the island’s socio-economic structure—which is to say the plantation/slave system—to mainland North America.

1st Earl of Shaftesbury

The settlement that Ashley and the proprietors founded was Charles Town, later Charleston, also named after their king, and it flourished. Unlike the northern section of the colony, which was sparsely populated over a wide region, Charleston was a hub of economic activity and soon became a thriving city. The Barbadian influence was strong. Nine of the early parishes of South Carolina were named after regions of Barbados.

The hedonistic nature of the island society was also derived from the West Indies. The materialistic culture was driven by the wealthy plantation owners whose competitive quest for wealth differed from the gentleman farmers of Virginia. According to one historian, “Material success, not character or honor, was the measure of an individual’s worth. And how a person acquired wealth was not important.”1

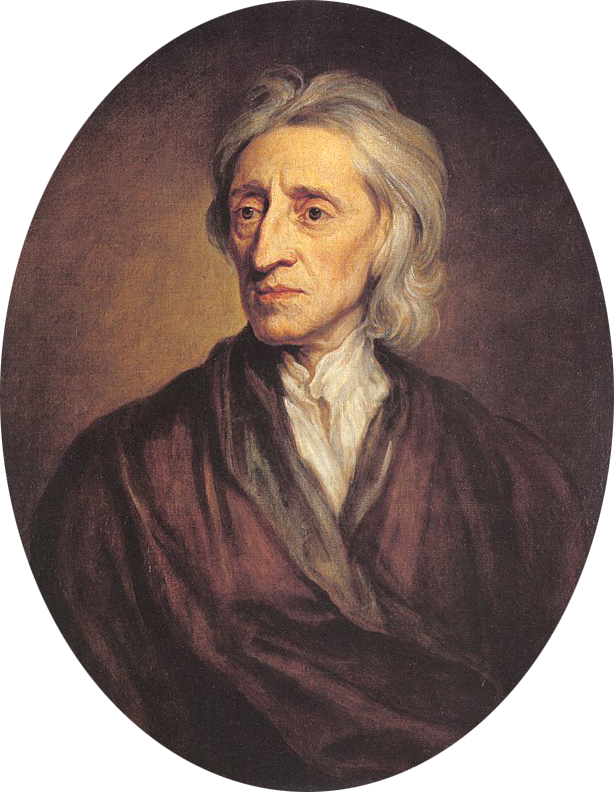

While the English maintained a slight plurality of the European population, immigrants from other countries were attracted to the Charleston region by virtue of the liberal laws set forth in Carolina’s Fundamental Constitution. This was a document written by John Locke, then a personal secretary to Ashley, which provided for religious freedom, naturalized citizenship for aliens, property rights and land grants, among other rights and privileges which were intended to attract settlers.

Not lost on the European population was the fact that the importation of African slaves was increasing the black population at an alarming rate. This was of some concern to leaders of the colony, not out of any regard for the African people, but out of concern for the safety of the white population in the event that the blacks could no longer be “controlled.” But the benefits of slavery to the plantation owners still outweighed their fears of slave revolt, and in 1720 the black population had officially grown larger than that of the whites. In some parts of the colony, the black population reached almost eighty percent.

Division

The division between North and South Carolina was surprisingly congenial and apolitical. In fact, the two colonies had greater border disputes with their opposite neighbors than with each other. This was largely because it was the proprietors themselves who divided the colony. In 1691 they changed the commission of Governor Philip Ludwell from “Governor of that part of Carolina that lies North and East of Cape feare (sic)” to “Governor of Carolina,” whose capital was in Charleston.2

Final division came in 1710 when it became clear that the northern residents of Carolina were too far from Charleston to participate in their own government. The proprietors appointed a new governor of North Carolina, “independent of the Governor of Carolina.” Clearly, it was the southern portion of the colony that retained the right to the name “Carolina,” but the division between north and south had been so natural and so gradual that the name “South Carolina” was also natural, and so it stuck.

All that was left was to draw a line between the two halves, and that was done fairly seamlessly in 1765, just in time for the beginning of the American Revolution movement. South Carolina can be said to have moved into independence on March 26, 1776. On that morning the last Provincial Congress was held in Charleston, and after adjourning, the same men returned that afternoon for the first legislative session of the South Carolina General Assembly. Official statehood would come after theAmerican Revolution and the drafting of theU.S. Constitution. South Carolina was the eighth state to ratify it, which they did on May 23, 1788.

Whatever happened to Carolana?

As noted in the chapter on North Carolina, a grant of land called “Carolana” was made in 1629 to Sir Robert Heath, attorney general to King Charles I. That grant was sold by Heath’s heirs to Daniel Coxe, physician to King Charles II. Coxe attempted to claim the land by sending his son to America in 1702. His son, also named Daniel, returned to England with a map of the explored region of his father’s claim. The grant included all of the land between 31 and 36 degrees latitude between the Atlantic Ocean and the “South Sea,” or Pacific Ocean, which by now included the already thriving colony of Carolina. One assumes that had Coxe successfully promoted his land, he would have had a boundary dispute on his hands, pitting his claim, which had originally come from Charles I, against the Carolina Proprietors whose land had been granted by Charles I’s son, Charles II.

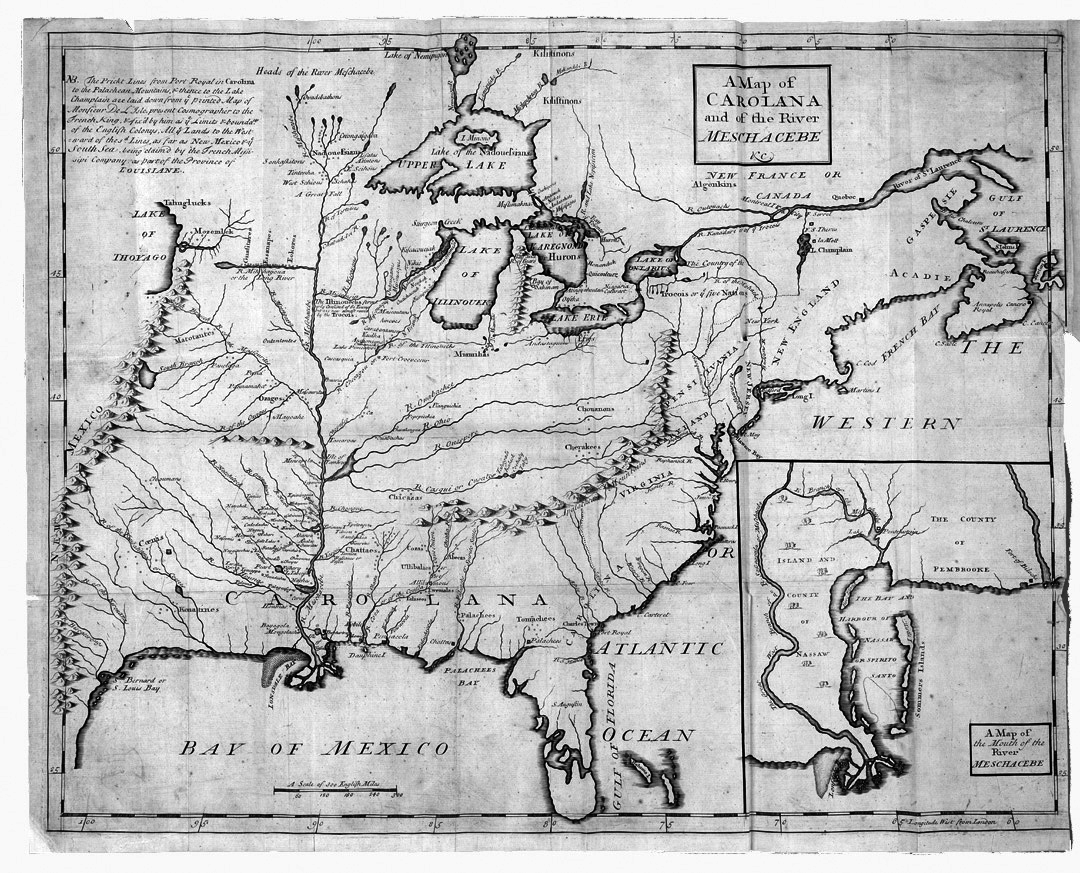

A map entitled “A Map of Carolana and of the River Meschacebe” was published in 1722 along with a promotional book inviting adventurers and settlers to the region, but Coxe was never able to colonize the vast grant. In 1769 his descendants exchanged “Carolana” for a portion of the Mohawk Valley in New York State. The map has remained of interest to this day because it is the first English map of the Mississippi Valley. Coxe used it to promote his notion of “symmetrical geography,” and it was used by Lewis and Clark in planning their expedition to the American Northwest.

End Notes

1. Edgar, Walter, South Carolina: A History, (Columbia, 1998), p. 37.

2. Edgar, p. 2.