NORTH CAROLINA

Her mom and dad went down to Charlotte

They’re not home to find us out…

—Ben Folds Five, Brick

In my mind I’m goin’ to Carolina…

—James Taylor, Carolina In My Mind

Tangling with my Carolina

You know the girl kept me up all night

—Blues Traveler, Carolina Blues

Standing Apart

Nerds think “Research Triangle.” Sports fans think “Tar Heels” or possibly “Duke.” North Carolina is perhaps the only southern state that doesn’t immediately make one think of slavery, the Civil War, and antebellum houses, though certainly all of those existed in North Carolina. Maybe it’s that word “North.” Or maybe it’s because, compared to its neighbors to the north and south, North Carolina seems unassuming, subdued, somehow less “southern.” In fact, in some quarters it has assumed the famous Ben Franklin quote that was originally meant to describe New Jersey: “a valley of humility between two mountains of conceit.” It is a state that has moved on from its past and emerged with a reputation as modern, new, fresh.

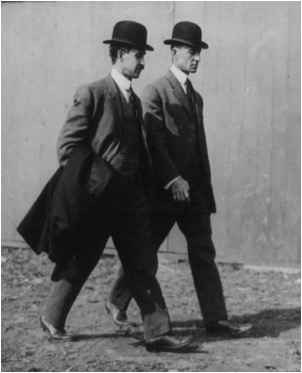

Indeed, one of North Carolina’s major sources of pride is its claim to the accomplishments of the Wright Brothers. “First in Flight” refers to them both—the Wright Brothers and the state of North Carolina. Kitty Hawk is one of those places in the United States that people know—they know why it’s famous, even if they don’t know exactly where it is. While Orville and Wilbur have undergone scrutiny and even some disparagement in recent years (modern scholars debating heatedly whether they were really the first to fly an aircraft), the state clings to them and their history, but it is a symbiotic relationship. They help each other—North Carolina props up the Wrights in their times of trouble, and the brothers link North Carolina indelibly to technological advances in aviation.

North Carolina has another important historical claim to fame. The very first attempt at English colonization in North America was the ill-fated Roanoke Island settlers in 1587, otherwise known as the “Lost Colony.” Sir Walter Raleigh, who held the patent for Virginia, sent the colonists not to Roanoke Island but to Chesapeake Bay, but his orders were countermanded by the Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, who was anxious to rid himself of the colonists and get back to raiding Spanish ships. Fernandes forced the group off at Roanoke Island, where they attempted to make a go of it. Their fate robbed North Carolina of the first English Colony, but gave it one of the most famous mysteries in American history. Of course, had the Roanoke colony succeeded, North Carolina might now be known as Virginia, Spain might never have gained such a foothold in Florida, and the whole eastern seaboard—indeed all of the Americas—could look a lot different on maps today.

Close, but no Cigar

Alas, the stand-alone name “Carolina” was simply not meant to be. It seemed destined for success when monarch after monarch was honored by it, but its history, and that of the two states which now share the name, is filled with near misses. Attempts at starting settlements failed, were driven back by storms and hurricanes, or were thrown off course and wound up in Virginia or Florida. Then, when it finally stuck as a place name in North America, the region it described was too big for it. So, just as the land was divided, so was the name.

The name Carolina was intended to remind us of King Charles— Caroluus being the Latin version of “Charles”, and Carolina being a feminine form of Caroluus. The question is...which King Charles? Three monarchs vie for that distinction, and most histories of the word mention all three: King Charles IX of France, King Charles I of England, and his son, King Charles II. All three became the namesake for some plot of land in America, but only one—King Charles II—is specifically tied to the states of North and South Carolina.

The Three Kings

King Charles IX of France was the earliest of the three, and was only twelve years old when his subjects set out boldly for “La Florida.” They aimed to take it from the Spaniards by settling the lands that Spain had virtually ignored since staking its claim in 1513. But while he did have a section of land in North America named in his honor, it wasn’t necessarily the region we now call the Carolinas. The explorer who honored Charles IX was Jean Ribaut who in, 1562, sailed to the mouth of a river he named the River of May, now called the St. John’s . Ribaut claimed the land in honor of King Charles IX by erecting a stone marker bearing the arms of the monarchy.

Ribaut, however, was not simply naming a colony, he was naming the land. Just as the English had “Virginia” and the Spanish had “La Florida,” the French deemed “Carolina” their dominion in North America ( southern North America, that is, as they already had a foothold in what is now Canada), however large or small it turned out to be.

Leaving the stone pillar on the beach for other Europeans to see from their ships, he then sailed north to what is now Parris Island, South Carolina, and instructed his men to build a small fortress. This he named Charlesfort , also in honor of his king, lest there be any mistake as to whom Ribaut was working for. Charlesfort was abandoned after eighteen months, but a new French fort was later erected at the Florida site. This one, called “Fort Caroline,” was destined to suffer a gruesome ending at the hands of the Spanish in 1565 (see Florida), and French Carolina ended with it. But France would have its North American empire. Almost a hundred years later another French king, Louis XIV, would have almost a third of the continent named for him.

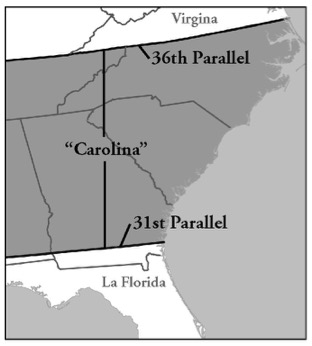

Which brings us to Charles number two. In 1629 King Charles I of England granted the region south of Virginia to his attorney general Sir Robert Heath. The borders of the grant stretched from 31 to 36 degrees North latitude (very close to the borders of the current Carolinas), and as with many of the royal grants in America, from the Atlantic Ocean to the “South Sea,” or Pacific Ocean. The king named the land “Carolana” after himself and included in Heath’s charter the powerful “Bishop of Durham” clause. In England, Durham County was situated on the northern border with Scotland, and its proprietor, or Bishop, was charged with protecting England from invasion by the Scots. The placement, naming, and powers of the proprietor of Carolana represented a southward push from Virginia. Clearly, King Charles was giving notice to the Spaniards in Florida of his claim to “Carolana” and his intention to defend it.

Heath made an unsuccessful attempt to colonize Carolana then transferred his grant to Henry Frederick Howard, Lord Maltravers, in 1638. Maltravers, the grandson of the Duke of Norfolk, was successful in creating the county of Norfolk in Carolana but no more successful than Heath had been at colonizing. Still, it was clear to settlers in Virginia that the lands to the south were considered by the king to be part of his domain, so the governor of Virginia began granting land south of that colony’s border, in what they referred to as the “Southern Plantation.”

In 1649, King Charles was executed by the Parliamentarians, and royal patents in America came to a halt. Many loyalists found refuge in Virginia, and the Southern Plantation began to swell with new settlers. A new name was applied: Albemarle County Colony, and it may have had as many as 500 settlers by the time of the Restoration in England.

Thus, we arrive at Charles number three. When King Charles II, who had been living in exile on the European continent, was restored to the throne in 1660, he wasted no time granting patents for new colonies in America. He granted New York to his brother, New Jersey to his friends Berkeley and Carteret (see New Jersey), Pennsylvania to the son of a major supporter, and Carolina to a group of eight proprietors who had been loyal during his exile.

Six of the Carolina proprietors are notable here for the names they placed upon the region:

Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon (Clarendon County)

George Monck, Duke of Albemarle (Albemarle Sound, County)

William Craven, Earl of Craven (Craven County, N.C. and S.C.)

Anthony Ashley Cooper (Ashley and Cooper Rivers)

Sir George Carteret (Carteret County)

John Lord Berkeley (Berkeley County, S.C.)

The last two proprietors would practically abandon their claim to Carolina in favor of a new grant to the north. Sir William Berkeley, who was governor of Virginia at the time of the grant, and Sir John Colleton of Barbados rounded out the group.

The grant was made in 1663, and then expanded the following year to include all of the land north to the Virginia border, including what the proprietors named Albemarle County (to Virginia, the aforementioned “Southern Plantation”) which was quite heavily populated and which Virginia claimed as her own, touching off a border dispute between the two colonies. The southern boundary was also moved, and its new placement near Cape Canaveral, Florida, engulfed the established Spanish settlement at St. Augustine. Like his father, Charles was challenging the Spanish.

Division and Independence

Also like his father, Charles II’s Lords Proprietor had difficulty settling and governing Carolina. It became clear almost instantly that not only was the region too large for a single government, but that it was divided geographically into a northern and a southern section. The southern region (see South Carolina) would not be finally settled for several years, and the northern section was full of settlers who resented the Proprietors and the series of rather corrupt governors whom they installed in Carolina. The settlers believed themselves either Virginians or true pioneers, independent and rebellious.

The southern boundary of North Carolina, therefore, was established earlier and more easily than the northern border. In 1691 Philip Ludwell was selected Governor of Carolina, and as such he would reside in the now revitalized southern city of Charles Town (Charleston). He was, however, to select a deputy governor for the northern section of the unwieldy colony, and he did so with care and discretion, selecting men who brought relative prosperity to “North Carolina,” as it came to be called.

Eventually, however, this situation proved chaotic, and to remedy the problem with a single document, the Lords Proprietor made the division between north and south official and permanent. On January 12, 1712 they commissioned a governor of North Carolina “independent of the Governor of Carolina.” The name “South Carolina” would routinely be used from then on to describe the southern region, but interestingly it was the North, the larger section, which would give up the sole use of the name in order to gain its separation from the southern region.

Cape Fear had always been the point of division between the two colonies, and the actual border would not be determined until 1735, but once it was surveyed the line was agreed to easily by North and South Carolina. Both states, however, would have much more difficulty with their opposite neighbors in settling disputed boundary lines.

North Carolina’s border with Virginia had been a source of resentment for over half a century before it was finally resolved. By order of King George II a group of surveyors were commissioned. They ran the line correctly according to the 1665 charter, and once and for all Virginia gave up its claim to Albemarle County in North Carolina.

By the time of the American Revolution, North Carolina was eager for independence. Its legislators were the authors of the “Halifax Resolves” in April of 1776 which, among other things, directed its delegates to concur with those of other colonies in declaring independence from England. Once the revolution was over, however, North Carolina was reluctant to join the Union. It was twelfth of the thirteen colonies to ratify the Constitution (ahead of only Rhode Island), which it did on November 21, 1789.