WYOMING

Out on the trail night birds are callin

Singin their wild melody

Down in the canyon cottonwood whispers

A Song of Wyoming for me

—John Denver, Song of Wyoming

Why, oh why, did I ever leave Wyoming?

Why, oh why, did I ever have to go?

Why, oh why, did I ever leave Wyoming?

Cause there’s a sherriff back there,

Lookin’ for me high and low,

And high and low

—Roy Rogers, Why Oh Why Did I Ever Leave Wyoming?

People-less

Wyoming of the twenty-first century has a reputation as a playground for the rich and famous. Movie stars and multimillionaires out do each other trying to acquire the most land closest to Jackson Hole (named for David Jackson, a fur-trapper in the 1820s). One reason for this is, no doubt, Wyoming’s allure as a state with wide open spaces and big blue skies, which is to say people like to go to Wyoming because Wyoming doesn’t have a lot of people. As a matter of fact, Wyoming has never had a large population. Even before Europeans, the region supported relatively few Indians, largely because buffalo did not thrive as well in Wyoming as they did to the south and east. Wyoming, according to the most recent U.S. Census, has the smallest population of any state in the union, smaller even than Rhode Island or Alaska, and since celebrities have begun buying up “ranches” by the thousands of acres, it is likely to remain that way.

Of course, even more than rich celebrities, Wyoming makes us think of cowboys and the old west. But unlike the Texas cowboy image—rough, loud, perhaps more prone to violence—Wyoming’s cowboy is solemn, probably alone (given the state’s dearth of...well, people), and serene. Wyoming perpetuates the old-west image with its Cheyenne Frontier Days celebration, one of the most famous rodeos in the world. Rodeos began as informal competitions among cowboys as a way to show off their ranching skills. Over the years, rodeos developed into popular community entertainment events that highlight ranching culture and industry, and there is no better place for this identity to thrive than Wyoming.

Photographer: Ralph Doubleday

Wyoming has another claim to fame, at least for those people who know where it is. Yellowstone National Park, the nation’s—indeed the world’s—first and oldest national park, occupies the northwest corner of the state, carving out yet another 3,472 square miles of Wyoming where people generally don’t live. Every year the Park experiences around three million visitors hoping to time Old Faithful just right or to possibly catch a glimpse of a grizzly bear or wolf in their natural habitat. So to put it into perspective, this single tourist attraction draws six times more people to the state every year than the number of people who actually live there.

Pennsylvania

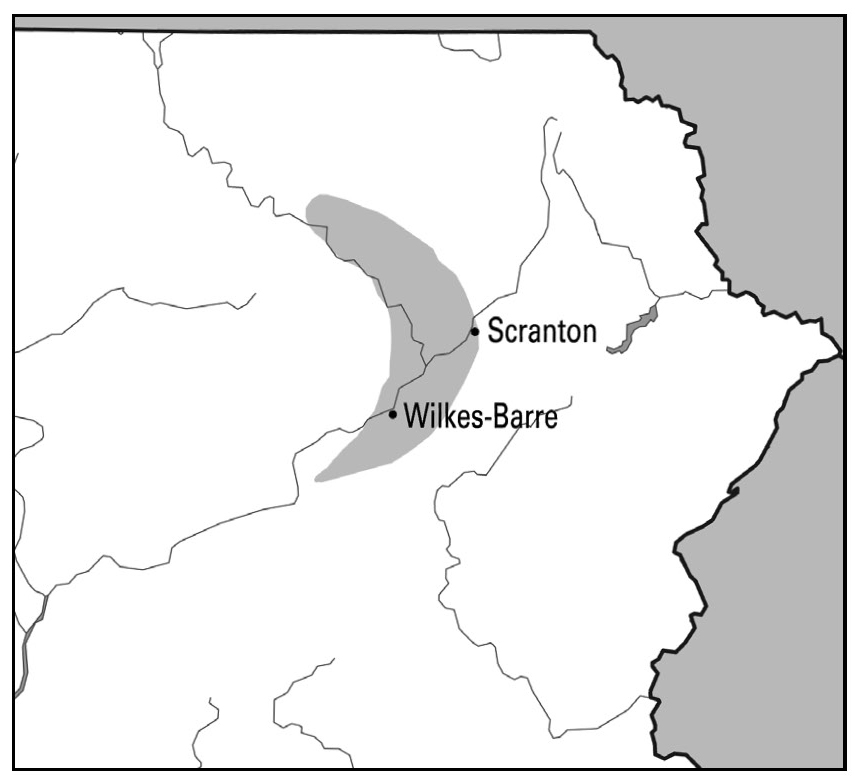

The story of Wyoming’s name begins in Pennsylvania, specifically in a small valley of the Susquehanna River basin near Wilkes-Barre. The Algonquin-speaking Delaware Indians called the place something like mscheweamiingwhich meant “large prairie place” or “big flats.” The missionaries of the 1700s had difficulty with the name (go figure) and shortened it to “Wayomik.”

In 1754 Connecticut asserted its claim to the valley by virtue of their Royal charter, which described the colony’s western border as the “South Sea,” meaning the Pacific Ocean. Boldly ignoring the conflicting claims of New York and Pennsylvania, the Susquehanna and Delaware Company of Connecticut purchased the valley, which they called “Waioming” or “Wyoming,” from the Iroquois Indians and made plans to settle it. Eight years later, they began to do so, but conflicts with Indians made the process troublesome and time consuming. By the mid 1770s the Wyoming Valley had several villages of “Connecticut Yankees” protected by a few small forts.

The American Revolution then saw an event that would thrust the name “Wyoming” into the national consciousness. With most of the men off fighting the war, one of the forts—called Forty Fort—was attacked on July 3, 1778, by a group of about 400 British soldiers and Loyalists and 700 Seneca and Cayuga Indians. Having won the battle, the attackers engaged in what has gone down in history as the “Wyoming Massacre” in which hundreds of settlers were brutally executed. As horrible as the massacre was, it became more graphic with each retelling, as the story radiated in all directions and frightened other settlers out of Pennsylvania and the Ohio Valley. In 1809, a Scottish poet named Thomas Campbell memorialized the massacre with his poem “Gertrude of Wyoming,” which became quite popular.

A monument to honor those who perished in the massacre was completed in 1830. About that time, thanks largely to the popularity of Campbell’s poem, Wyoming became a popular name for new cities and counties. Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia (in what later became West Virginia) all created counties using the name, and at least five states and one Canadian province used the name for newly incorporated cities. But as “Wyoming” became more and more popular, the meaning of the word, and indeed the memory of the massacre, began to fade.

The Two Ashleys

The region that would become Wyoming began to be explored shortly after the Lewis and Clark venture of 1803-06. Fur trappers and traders were among the most prominent explorers of the area, and one of the most famous of these was General William H. Ashley. Between 1822 and 1826, Ashley operated a fur trading company with his partner Andrew Henry, and hired such Mountain Men as Jedediah Smith and David Jackson to trap furs in the northern Rocky Mountains and to engage the natives of this region for purposes of trade. Ashley and Smith kept journals of their explorations, which became the basis for much geographical knowledge of the region during the 1800s. Of course, when Ashley was exploring, there were very few place names to which he could refer. In his narrative, he refers to many of the rivers by name, but in other places struggles to find a point of reference for the area he is describing:

Our situation here was distant six or eight miles north of a conspicuous peak of the mountains, which I imagined to be that point described by Major Long as being the highest peak and lying in latitude 40 N., longitude 29 W.1

From 1831 to 1837, William Ashley served as a Congressman from Missouri (which at that time included modern Wyoming), using his extensive knowledge of the western natives in his work on the Committee on Indian Affairs. It is unclear if General Ashley has any connection to the naming of Wyoming, but he is integral to Wyoming’s early history, and poses a fascinating mystery as to the origin of the state’s name because of...well, his name.

You see, his last name is the same as that of another Congressman, James M. Ashley, who was born in Pennsylvania around the time that William Ashley was traipsing through the Wyoming Rocky Mountains. It is not clear if the two men were related, though chances are there was at least a distant familial connection. James Ashley’s father John was born in Virginia a few miles from where William Ashley was born, and only two years later.

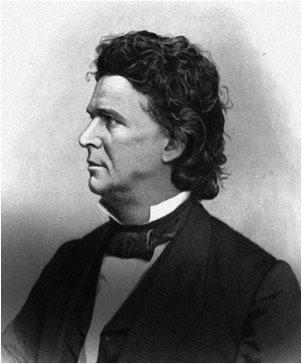

James M. Ashley was known as the Great Impeacher for having initiated impeachment proceedings against Andrew Johnson . Ashley, a staunch abolitionist, opposed Johnson on many civil rights issues and had become convinced that Johnson was involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was impeached, but not convicted, and Ashley’s role in the proceedings doomed him to the loss of his congressional seat in the elections of 1868.

The Johnson impeachment virtually consumes James Ashley’s biography, but he did do other things while he was in Congress. In particular, he proposed the new Territory of Wyoming in 1865. The Congressional Record entry for this proposal is the earliest mention of the name Wyoming being used to describe the region the state now occupies.

Ashley’s motives in proposing the creation of Wyoming were suspect. He was intent on mitigating the power of Brigham Young, whose lofty position in Utah was the source of much angst for many congressmen. One means of suppressing the Mormons was to decrease the size of their territory, and Ashley’s proposed new territory took a sizable chunk out of Brigham Young’s domain. This effort to organize Wyoming Territory did not succeed, but it did propose the name that would ultimately be used.

The name Wyoming was a natural choice for a newly proposed territory. It was certainly becoming popular—a township in Ashley’s home state of Ohio had just adopted the name when it incorporated in 1861—and it originated in the state where Ashley himself was born…Pennsylvania. In the 1860s it was common for new territories to have aboriginal names—Dakota, Minnesota, Kansas, Nebraska. And given that Ashley had never visited the region for which he was proposing territory status, and that he knew very little about it, almost any Indian name would do. Wyoming was popular. It was being applied to towns and counties all over the east...why not this new western territory?

James or William?

By 1867 the population of Wyoming was growing relatively quickly, thanks in large part to the construction of the Union Pacific railroad that passed through a southern strip of the state. Officially the entire region was Laramie County in western Dakota Territory, but unofficially the name Wyoming was beginning to take hold, thanks primarily to the efforts of a newspaper publisher named Legh R. Freeman (more on him later).

In 1868 the new territory of Wyoming was once again proposed in Congress, this time for more pragmatic than political reasons. Several thousand people now lived in the region, mostly in Laramie and Cheyenne, and Dakota Territory was too large to govern them. They wanted separation, and Dakota, who had political problems of her own, wanted to be rid of them.

In June of 1868 the Senate debated several amendments to the bill creating the Wyoming Territory, one of which would change the name to “Lincoln.” During the debate, which lasted for some time, several other names were proposed as well including Cheyenne, Shoshoni, Arapaho, Sioux, and Pawnee—all names of Indian tribes from in or near the region—as well as Platte, Big Horn, Yellowstone, and Sweetwater—names of regional rivers.

The debate became heated in certain places, but one exchange stands out:

Mr. NYE: In my opinion, if the name is to be changed at all, from what the committee proposed, it had better be Wyoming.

Mr. SUMNER: I ask the chairman if the name of Wyoming is not found in the Territory?

Mr. YATES: No, sir; it belongs to Pennsylvania.

Mr. SUMNER: I know, originally; but then what suggested this name for this Territory?

Mr. DOOLITTLE: It was suggested by General Ashley.

Mr. SUMNER: But what suggested it to General Ashley?

Mr. DOOLITTLE: Because it is a beautiful name.

Mr. Sumner doesn’t say Mister Ashley or Congressman Ashley. He says General Ashley. Now, perhaps he misspoke, or perhaps he was simply mistaken. General William Ashley, who had been dead for decades by the time of this debate, was certainly famous for his connection to the region, but there is no record of him referring to any part of it as Wyoming. James M. Ashley, who certainly did use the name, and used it first as far as anyone can tell, was never a General, nor did he have any military background whatsoever. So to which Ashley was Mr. Sumner referring? It’s a question we are unlikely to ever know the answer to.

At any rate, by the end of the debate, Wyoming, a name that originated in Pennsylvania, and gained fame because of a horrible massacre, won the day. Among the reasons the senators gave for settling upon "Wyoming" were that it was easy to spell (unlike mscheweamiing) and, of course, that it was euphonious.

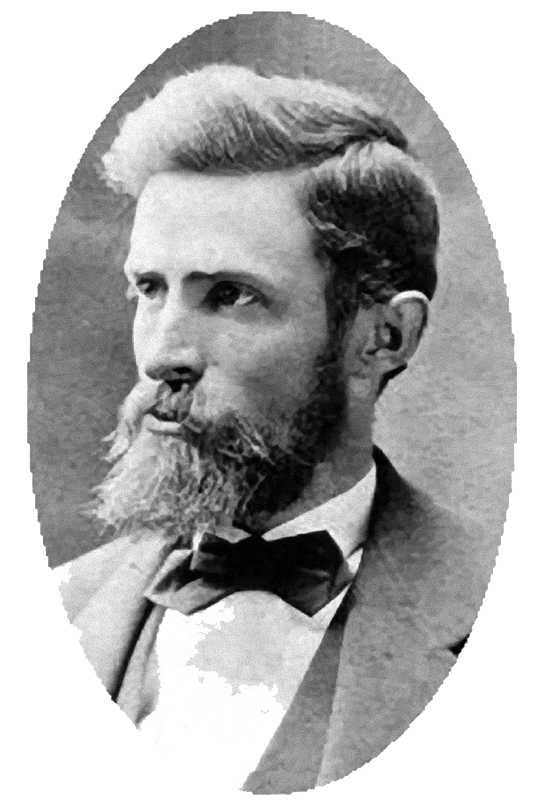

Legh Richmond Freeman

Legh R. Freeman, the afore mentioned newspaper publisher, claimed it was he who proposed the name Wyoming for the new territory, but then he claimed a lot of things. Freeman was a colorful (to put it mildly) man who distributed a newspaper he called the Frontier Index in 1867 and 1868. Known historically as “Hell on Wheels,” the Frontier Index was one of a handful of newspapers of the era that followed a railroad as it was being built and distributed news to the small towns and villages that cropped up along the tracks.

Using a printing press that he “found” abandoned by a group of Mormons making their way across Nebraska to Utah, Freeman and his brother published the Frontier Index along the Union Pacific line from Julesburg, Colorado, in July of 1867 to Bear River, Wyoming, in November of 1868. His operation ended there, tantalizingly close to Promontory, Utah, where the railroad would connect with the Central Pacific line to create the first cross-country railroad. Freeman claimed that a mob, angered by his accusations of fraud on the part of railroad officials, destroyed his printing press and burned his office.

Freeman would go on to publish newspapers in Utah and Montana and eventually moved to Washington. While he was instrumental in popularizing the name Wyoming, he rarely missed an opportunity to exaggerate his role in doing so as he did in almost every other of his dubious accomplishments. In a bid for U.S. Senator in 1909, he wrote the following for the Yakima Morning Herald:

“I have taken an active part in the creation of the states of Nebraska, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Montana, and Washington...as I blazed a trail for the vanguard of civilization across the western two-thirds of America and I named Wyoming.”2

Wyoming historian Dr. C. G. Coutant details Freeman’s claim: “Freeman...makes the claim that he, in the spring of 1866, while en route from Fort Kearney, Nebraska, to Fort Laramie to attend a Peace Conference, wrote a letter for publication to his paper and dated this correspondence ‘Third Crossing of Lodge Pole Creek, Wyoming Territory.’ This, he says, was the first time the name was applied to the ‘southwestern half of Dakota.’”3

Given that, by his own account, Freeman “named” Wyoming the year after James M. Ashley proposed the territory by that name in Congress, Freeman’s boast rings hollow. Colorful, but hollow.

Equality

The territory of Wyoming was at last created despite objections from a surprising source. James M. Ashley had, by 1868, visited the region and was now opposed to the organization of the territory on the grounds that “...there was not fertility enough in the soil to subsist a population sufficient for a single congressional district .”4 Nevertheless, on July 25, 1868, the territory of Wyoming was formed, one of two parallelograms drawn on the west—four straight lines, four right angles, and no natural borders. These same unnatural boundaries would be taken to statehood, when President Benjamin Harrison signed Wyoming into existence as the 42nd state in the Union on July 10, 1890.

However small, the population of Wyoming proved themselves forward-thinking when their first territorial legislature in 1869 gave women the right to vote. This right was never repealed and is a source of great pride (as well it should be) for Wyoming, earning the state its nickname, the Equality State.

End Notes

1. Dale, Harrison Clifford, The Explorations of William H. Ashley and Jedediah Smith, 1822-1829 (Lincoln, 1991), p. 125.

2. Heuterman, Thomas H., Movable Type: Biography of Legh R. Freeman (Ames, 1979), p.137.

3. Coutant, Dr. C. G., History of Wyoming and (The Far West) (New York, 1966), p. 622.

4. Larson, T. A., History of Wyoming (Lincoln, 1978), p. 67