WISCONSIN

“Cheese!!!, Gromit! CHEEEESE!!!”

— Wallace and Gromit

Minerva Mayflower: ...on display for three days only at the Louvre in Paris.

Hudson Hawk: As opposed to the Louvre in Wisconsin?

— Hudson Hawk

Hey little girlie in the blue jeans so tight

Drivin’ alone through the Wisconsin night

—Bruce Springsteen, Cadillac Ranch

The Cheese State

Wisconsin means cheese...and cows, which produce milk to make cheese...and Green Bay Packers, whose fans wear foam cheese on their heads. Cheesecake, cheese balls, Cheetos®...if Cheese Whiz was a dairy product it would be made in Wisconsin. Wisconsin is home to the Wisconsin Specialty Cheese Institute. The University of Wisconsin at Madison offers a short course in Cheese Technology. Three of the state’s nicknames refer to its dairy industry: the Dairy State , America’s Dairyland , and, of course, the Cheese State . Wisconsin is in that part of the country that makes us think of Norwegian Lutherans and bachelor farmers. The uninformed perception is that some time in Wisconsin’s early history, the land was so conducive to dairy farming that all of the dairy farming immigrants to the U.S. moved there to engage in the traditional family occupation.

Well, almost. Actually, the early immigrants to Wisconsin were wheat farmers. In the early 1800s, Wisconsin produced a large percentage of the nation’s wheat, until diseases, mineral depletion, and falling wheat prices forced the Wisconsin farmers to diversify.

With the land spent from years of over-planting wheat, the farmers found that it made good grazing land for dairy cows. The dairy industry grew quickly but still asserted only regional dominance. Around the mid 1860s, the dairy farmers in Wisconsin began to organize into professional associations.1 It was this consolidation of marketing and technological expertise that allowed Wisconsin to dominate the cheese and butter markets.

Beer is the other commodity strongly associated with Wisconsin—though primarily only with the city of Milwaukee—and the industry that produces it developed in a similar way to that of cheese. Beer makers in Milwaukee were forced, because of the relatively small population in that region, to look to outside markets to sell their beer.2 The organization of marketing strategies and technology efforts—as opposed to any natural regional advantage—was what made Milwaukee, Wisconsin the “Beer Capital of the World.”

The River

As with many states, Wisconsin takes its name from the river that winds through its heartland. The earliest mention of the name “Wisconsin” is traced to 1672 and to two French adventurers, Joliet and Marquette. Joliet wrote of a river he called “Miskonsing” that he followed with a group of natives, who had told him of a much greater river they called the “Missisipi”(sic). Other French explorers and traders exploited the region for its furs, labeling the river on maps with variations on the same name Jolliet had used. Eventually the initial “M-” was replaced with “Ou-” (the closest thing the French language has to a “W”), which was said to more closely mimic the Indian name. The French traded for furs with natives along the “Ouisconsin” and used the river as a route to the Mississippi, but its banks were not permanently settled by the French.

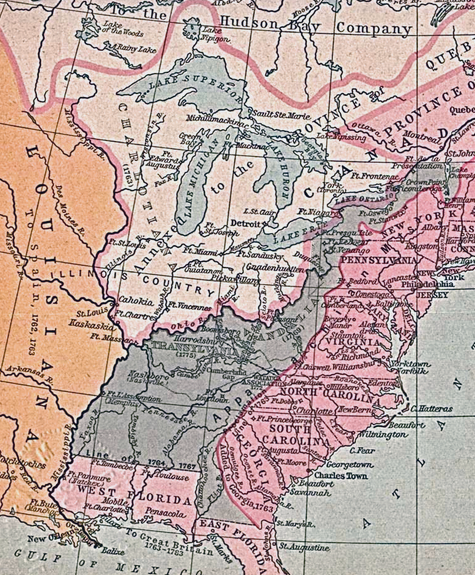

The name “Wisconsin” was barely known to the British who, by virtue of their victory in the French and Indian War in 1763, now claimed the region as their own. The banks of the river were considered part of “Illinois Country,” which some British subjects were anxious to colonize. In 1763 a pamphlet was circulated in Edinburgh, Scotland, that laid out a new colony called “Charlotiana,”3 after Queen Charlotte, the young bride of King George III. Charlotiana would have encompassed what are now the states of Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan. But instead of granting the colony, King George forbade it, as well as any other new colonies west of the Alleghanies, until a policy of negotiating with the Indians could be developed.

In 1766 a surveyor and war veteran named Jonathan Carver set out to explore Wisconsin for England. Carver, guided by natives, canoed down what he called the “Ouisconsin” River as it wound its way around the modest Baraboo Range. Shortly after Carver’s explorations, the name “Wisconsin” began appearing on maps with its modern spelling, as well as several variations.

As for the word’s meaning, there are books and web sites that assert a certain definition of “Wisconsin” with great confidence. The most authoritative of these sources claim one of two different meanings for the word: 1) that it is a Chippewa word for “grassy place” or 2) that it is an Indian (of unspecified linguistic stock) word for “a gathering of waters,” referring to the fact that the river’s source contains many tributaries. The second of these definitions may stem from the fact that the Winnebago Indians called the same river “Neekoonts-Sara,”meaning “gathering of waters” or “gathering river.”4 Most historians agree, however, that the origin of the word “Wisconsin” is lost, and that it continually defies attempts to derive its true meaning.

Last, but not Least

After the American Revolution, the land which now constitutes Wisconsin was part of the Northwest Territory, or “Old Northwest,” which the new United States of America now claimed. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided for this region—the land west of the Alleghany Mountains, north of the Ohio River, and east of the Mississippi River—to be divided into no less than three and no more than five new territories which would eventually become states. Wisconsin would be the fifth and last of these, and would not be named a territory until well after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. So besides the Northwest Territory, the land we call Wisconsin was also eventually part of Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan Territories.

Wisconsin was finally divided from Michigan Territory in 1836, largely through the efforts of a federal judge named James Doty. Doty was said to have favored the name “Chippewau,” and others suggested the name “Huron,” but “Wisconsin,” the name of the region’s dominant river, became the favorite. Though Doty fought hard to maintain what he believed was the most authentic spelling of the word (i.e., closest to the native pronunciation) by changing the “c” to a “k,” and though “Wiskonsan” and “Wiskonsin” appeared in some documents, “Wisconsin” was the final form approved in the Organic Act for the territory on April 20, 1836.

Borders

The Northwest Ordinance recommended borders for the states that would be created, but by the time it was Wisconsin’s turn, the United States was a substantially larger country, and Manifest Destiny was just beginning to take hold. The organization of territories and states was no longer an experiment, but an established process, and it was clear that states would be formed out of more than just the “Old Northwest,” but also out of lands west of the Mississippi River, and possibly beyond even the Rocky Mountains.

Wisconsin’s first formation as a territory began when Michigan achieved statehood. Now officially “Wisconsin Territory,” it included what is now Minnesota and much of the Dakotas. What it did not include was Chicago, which had been tacked on to Illinois at the last minute of its organic process by moving the “recommended” northern border north about 60 miles. (See Illinois.) James Doty had been troubled by the maneuver, but as one history book puts it,

“Generations of pious Badgers have since congratulated themselves that the congressional interference placed turbulent Chicago in Illinois.”5

Also not attached to Wisconsin was that section of land to the north and east of the Menominee River extending all the way to Lake Superior, the section that had been included in the state of Michigan when it was created. We call it, of course, the Upper Peninsula , and why it is part of Michigan, and not Wisconsin, is not immediately clear by looking at a map. In fact, it’s not clear at all unless one happens to live there; and sometimes not even then. The U.P. is discussed at greater length in the section on Michigan, but generally because Michigan and Illinois were created first, and because of Wisconsin’s small population, its edges were whittled away by other states and territories with more political power.

Not insisting on Chicago or the U.P. had one fortunate effect on Wisconsin. The legislation creating the new territory

“sailed through Congress smoothly...accompanied by the usual hyperbole about the hazards of lawlessness and Indian depredations from which this new status would somehow shield the intrepid pioneers.”6

Before statehood, Wisconsin’s border with Minnesota had also to be decided. The Northwest Ordinance, which still guided the organization of the region, stated that no more than five states were to be created out of the Old Northwest. But when it came time to draw the western border of Wisconsin, there were strong arguments for placing it at the St. Croix River instead of the Mississippi, as had been specified in the Ordinance. Opponents argued the illegality of this border, asserting that Minnesota constituted a sixth state within the Northwest Territory, but the objections were relatively weak and short lived, and the desire for statehood stronger than the desire for the entire St. Croix valley.

Wisconsin statehood finally came on May 29, 1848 with the signature of President James K. Polk. It was the thirtieth state in the union, and its birth marked the end of the Old Northwest. From then on, the Northwest Ordinance was a historical guideline—a precedent, but no longer a law. Wisconsin completed the puzzle of the eastern United States. Except for West Virginia, Wisconsin was the last state to be created east of the Mississippi River, and from 1848 on, the state-making efforts of the nation turned to the far West.

End Notes

1. Gibbens, Jeff, et al, “A Brief History of…Economics in Wisconsin,” http://www.scils.rutgers.edu/~dalbello/FLVA/background/economics.html, created 5/17/2000, accessed 7/30/2009

2. “Why Milwaukee?” BeerHistory.com, http://www.beerhistory.com/library/holdings/milwaukee.shtml, accessed 7/31/2009

3. Alden, George Henry, “New Governments West of the Alleghenies Before 1780,” Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin, Historical Series Vol 2, No. 1, p. 12.

4. “Traditions and Recollections of Prairie Du Chen,” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, vol. IX, p.301.

5. Nesbit, Robert C., Revised and updated by William F. Thompson, Wisconsin: A History, (Madison, 1989), p. 122.

6. Nesbit, p. 123.