WASHINGTON

“I can’t believe it,” said the tourist. “I’ve been here an entire week and it’s done nothing but rain. When do you have summer here?”

“Well, that’s hard to say,” replied the local. “Last year, it was on a Wednesday.”

—Old Joke

“I cannot tell a lie, father, you know I cannot tell a lie! I did cut it with my hatchet.’’

—From "The Cherry Tree" by Mason Locke Weems in his book,

Life of George Washington; with Curious Anecdotes,

Equally Honorable to Himself, and Exemplary

to His Young Countrymen

George Who?

A hundred years ago the word Washington might have inspired the image of the father of our country. Today it is more likely to make us think of a monolithic software company run by the richest man in the world, or the wildly famous purveyor of coffee whose ubiquitous corner-front stores can be found anywhere in America.

Of course, multibillion-dollar corporations aside, the name Washington produces other images too. Apples, for one. The state produces more than half of the “eating apples” consumed in the U.S. And rain. Washington is among the wettest and foggiest of all the states, the western coastal region sometimes going weeks without a clear day. Also Mount St. Helens. In 1980 the world was fixated on images of the cataclysmic destruction caused by the sudden eruption of this volcano. And can anyone hum the theme song from Frasier ?

And speaking of Frasier , that massively popular spin-off from Cheers sets itself in Seattle, the state’s largest, and arguably most well-known, city—though not, to the surprise of many, its capital. (Olympia) And along with the enormously successful TV sitcom, the coffee, the Space Needle, the Seahawks, and, well, the rain, Seattle-ites may attribute part of the fascination with their city to one particularly unusual Seattle institution: Grunge music.

Properly coined the “Seattle Sound,” this cult-culture music scene started small, in garages and among a young, eclectic, and fiercely loathe-to-be-labeled youth, and then exploded in the mid-1980s. It permeated the mainstream music of the world with its legions of longhaired and defiant adolescents, who rejected the “Me Generation” icons of their elders in favor of the angst-filled teen anthems of Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Alice in Chains. And it all started in Seattle, in Washington, our only post-revolution state named for a specific person.

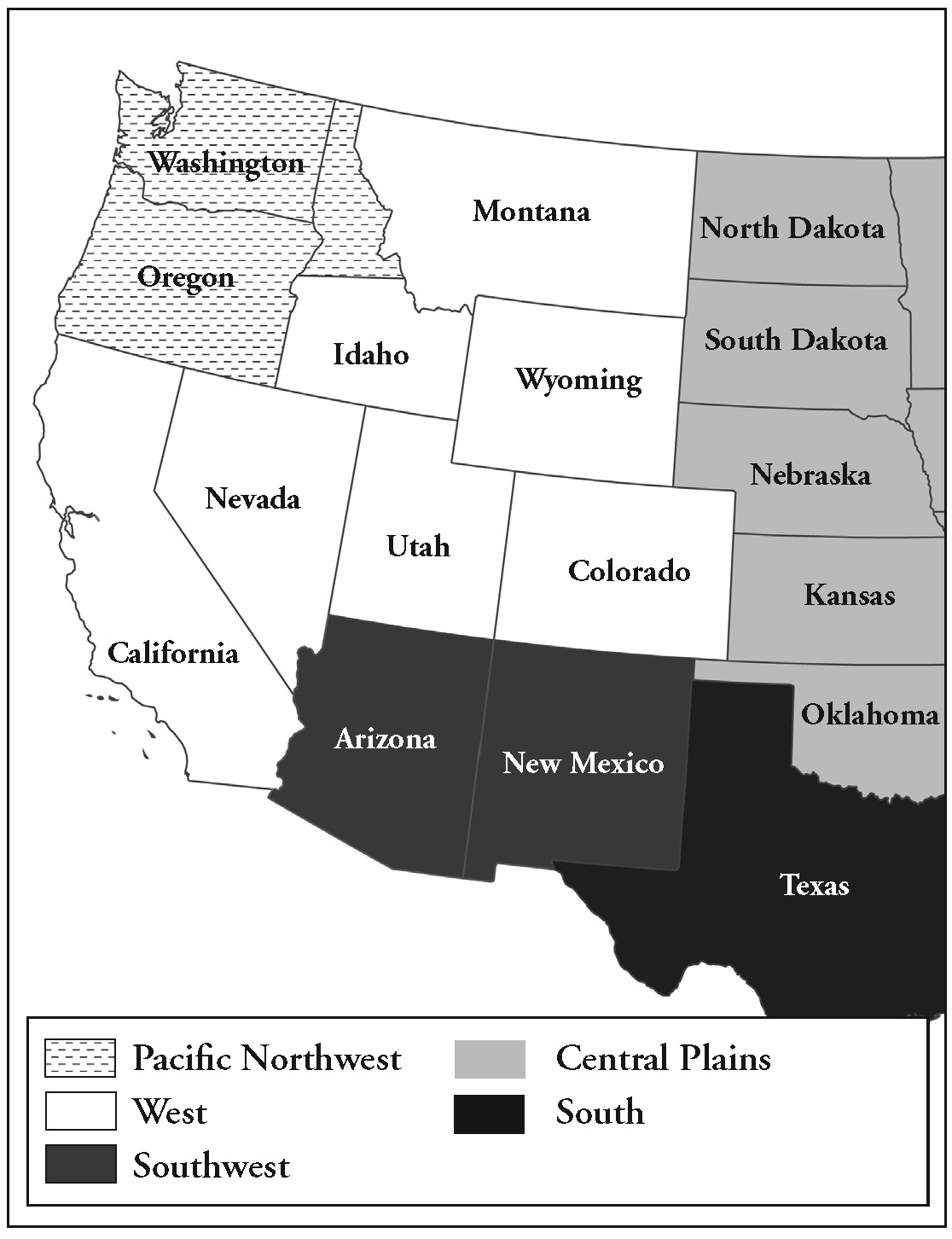

Pacific Northwest

Washington was carved out of the Oregon Territory and shares many of the same dimensions and geography of its southern neighbor. This creates a common dilemma for young geography students, the problem of being unable to remember “which one is on top.” Well, Washington is indeed the one on top, and the two of these states along with a portion of Idaho make up the Pacific Northwest, a name notable for its imprecision.

One might think that the phrase “Pacific Northwest” is redundant. After all, Washington and Oregon are in the northwest corner of the country (excluding, of course, Alaska, which not everyone does). The fact that the Pacific Ocean lies to the west of them seems irrelevant. The problem is the word “northwest” and the evolution of what it has come to mean.

After the American Revolution, the Northwest Territory was all the land west of the Appalachian Mountains, north of the Ohio River, and east of the Mississippi River. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, one of the defining documents of our nation, was written for the purpose of organizing this massive region, which the United States claimed from Britain and her Indian allies after the war. A few years later however, in 1803, the Louisiana Purchase was made, and the Northwest Territory wasn’t so northwest anymore. It was more midwest, and so that is the word that began to describe it.

But by 1848 the United States officially laid claim to all the land between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, from the 49th parallel south to a still-fuzzy (but close to its current placement) border with Mexico. Now the term “midwest” didn’t even seem appropriate, but it was fairly cemented and stuck relentlessly. That meant that the word “west” must mean everything west of “midwest.” And so our geographical vocabulary had to expand.

The middle of the country became the “central plains,” except for Texas, which is no doubt a “western” state. (Oddly,Texas is rarely described as “southern,” even though it certainly went the way of the South in the Civil War, and its southern tip is south of every other “southern” state except Florida.) Other western states are Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Montana, California, and most of Idaho. The “Southwest” is Arizona and New Mexico. California eventually became synonymous with “west coast,” leaving only the two states north of it to find their geographical distinction. “Northwest” by now had not only been appropriated by the midwest but realistically could describe a quarter of the country, way too broad a term to be useful to, say, your average meteorologist.

And so we arrive at “Pacific Northwest.” It is a descriptive phrase, accurate, and even euphonious. And most importantly for our discussion, it is where Washington is.

Which Washington?

When speaking of Washington, one often feels the need to distinguish it from our nation’s capital, and so, as with New York, we say Washington State to distinguish it from the city with the same name. This is a source of angst for many a Washingtonian, as well as for a few place-name historians:

...the duplication was one of the most unfortunate events of our naming-history...the two Washingtons (not to mention all the smaller ones) have grown steadily in importance, necessitating an ever more frequent and tiresome mention of “Washington State” or “Washington, D.C.” The two initials have become attached to the name of the national capital like an ugly parasitic growth.1

But interestingly the name “Washington” was bestowed in part to avoid such confusion.

As with “Lincoln” and “Jefferson,” the name “Washington” was often proposed as a state name. In fact, one of the very earliest states created by Congress very nearly bore that name. When the Northwest Territory (that is, the first Northwest Territory, not the Pacific Northwest) was initially divided, before a name was finally settled on for what is now the state of Ohio, the name proposed for the remaining portion of the territory was Washington . After committee debate, it was changed to “Indiana.” Then, in 1817, the Mississippi Territory and again in the 1840s the Minnesota Territory both had the name “Washington” proposed for them, but it never stuck.

When the residents of what was, in 1853, called “Northern Oregon”—that section of the Oregon Territory north of the Columbia River—petitioned for organization as a separate territory, they proposed the name “Columbia” for themselves. It was Richard H. Stanton of Kentucky who, when the petition was read in the House of Representatives, suggested changing the name to “Washington.” He argued that there was already a “District of Columbia,” and that using that name for a new territory would be too confusing. Historian Terence Cole wrote an excellent article in 1994 for the journal Columbia lamenting the naming of Washington , and in it he points out that Stanton had close ties to D.C.—he was born and raised there, and as a congressman used his chairmanship of the Public Grounds Committee to fight for the building of the Capitol dome which became known as “Stanton’s Monument.”2

Alexander Evans, U.S. Representative for Maryland pointed out a flaw in Stanton’s argument. He noted that countless places in the country already honored Washington, and that “our geographical nomenclature has become such a mass of confusion that it is almost impossible, when you hear the name of a town to know in what part of the world it is, much less to know in what part of the United States it may be found.” Evans’ argument was followed by a suggestion from Stephen A. Douglas, the chairman of the Committee on Territories, that instead of “Washington,” the new territory be named “Washingtonia.” It probably sounded just as silly to Congress in 1853 as it does to us today, and so the suggestion was ignored.

When the debate was over, the long-dead father of our country had won the day. “Washington Territory” was signed into existence by President Millard Fillmore on March 2, 1853.

You Named it What?

Still, opposition to the name raged on. James M. Ashley, a powerful representative from Ohio who served three terms as the chairman of the Committee on Territories, led the charge. Ashley presided over the creation of many western territories and was often passionate about how to name them: “My purpose was to give each territory a euphonious name...and at the same time use a word that should appropriately describe the topography of the country.” Historian Cole writes that if Ashley had had his way, the name “Washington” would have been erased from the map in the 1860s.3

Indeed, Ashley was not alone among congressmen. During the debate about the naming of Wyoming in 1868 Representative Charles Pomeroy from New York lamented the naming of Washington Territory. In response to suggestions that the proposed territory of Wyoming be named instead “Lincoln,” Pomeroy said, “We have never had any state named after any man, however good or great. We have the Territory of Washington, to be sure; but when it becomes a state I doubt very much whether it will be called the State of Washington.”

Pomeroy was, of course, mistaken. Delaware, the Carolinas and New York were all named after specific men, and Virginia and Maryland were both named for specific women. No doubt he was excluding them based on the fact that Congress was not responsible for those names, but this does not make his assertion any more correct.

Regrets over the naming of Washington continued even after statehood. Washington novelist Nard Jones wrote in 1947,

“There was a great galaxy to choose from. Names like Quillayute, Pysht, Chewelah, Klickitat, Washougal, Snoqualmie, Okanogan. Names wasted on streams and waterfalls, mountains and towns.... I mean only to say that I think we would be handsomer in Indian feathers or a coonskin cap than in a cocked hat.”

In the 1990s the state tourism department of Washington adopted the self-conscious slogan “The Other Washington” as an advertising gimmick to distinguish it from that “other” one on the east coast. After all these years Washington seems to have finally made peace with its home in the “Pacific Northwest”—home to Microsoft, Starbucks, and a brand of music all its own.4

Boundaries

Washington did indeed take its name on to statehood, but statehood did not come until 1889. Washington remained a territory for thirty-six years, longer than all but five other states, during which time its borders were debated and changed more than once.

The northern border, the one with Canada, was actually settled just before Washington was separated from Oregon. In 1846 the U.S. signed the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain, which extended the 49th parallel border between the U.S. and Canada from the Rocky Mountains all the way to the west coast, except for the southern half ofVancouver Island, which Britain fought successfully to keep. In return, the British gave up any rights to what they called New Albion or Nova Albion (Latin for New England ), what we call Washington and Oregon. This agreement inflamed those Americans in the Pacific Northwest, whose militant motto had become “Fifty-four forty or fight,” referring to their wish to move the northern boundary of Oregon Territory all the way north to the southern tip of Alaska. But the treaty avoided yet another war with Britain, at a point when America itself was becoming severely divided over slavery.

Washington Territory’s southern and eastern boundaries were also disputed, mostly in an effort by Washingtonians to maintain or increase their population. An attempt by Oregon to annex the Walla Walla region was successfully fought off, and once Idaho was created, Washington’s eastern border was fixed at 117.5 degrees W longitude.

These are the borders that Washington carried to statehood along with its self-conscious name. In November of 1889, Benjamin Harrison created, with the quickness of his signature, four states within a span of nine days: North and South Dakota on the 2nd, Montana on the 8th, and Washington, as if it hadn’t waited long enough, on the 11th. It was the forty-second state in the Union.