VIRGINIA

Homesick, tired, all alone in a big city

Why should everybody pity me?

Nighttime falling, and I’m yearning for Virginia.

—Billie Holiday, Sleepy Time Down South

Carry me back to old Virginny

...

There’s where I labored so hard for old Massa,

Day after day in the field of yellow corn;

No place on earth do I love more sincerely

Than old Virginny, the state where I was born.

—James A. Bland, Carry me Back to Old Virginny

She never comprimises,

Loves babies and surprises,

wears high heels when she exercises

Ain’t that beautuiful

Meet Virginia

—Train, Meet Virginia

“Virginia is for Lovers” (...of History)

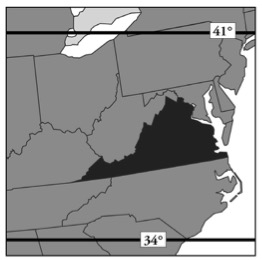

Original, archetypal, earliest, authentic, the first.... No matter which descriptor you use, when it comes to states, it is clear you’re probably talking about Virginia. Even today, this maiden state is perhaps best known as the original of the original thirteen colonies. Essentially, early American history is Virginia history, and the state features some of the most historic sites in the country.

When exploring Virginia, it is important to note that there are two very distinct regions: northern and southern. Due to its proximity to Washington D.C., northern Virginia is comprised mostly of suburbs, and its industry is hi-tech and scientifically oriented. And contrary to what many Americans might believe, the Pentagon is actually located in Arlington, VA—a fact that corrects many references to the 9/11 terrorist attack on that building as being an attack on Washington, D.C.

Southern Virginia is considered just that: a southern state. Tobacco fields cover a generous portion of the southern counties, and coal mining and other mineral extraction are common industries.

Aspects of Virginia’s rich history can be attributed to the original colonists’ European influences, particularly in the areas of art and culture. The genius of one of Virginia’s most famous architects—and third American president—Thomas Jefferson can still be seen today. Monticello, Jefferson’s Palladian masterpiece home, and the Virginia State Capital building are probably the two most noteworthy structures designed by this Founding Father. However, for those who find classical European architecture a bit too stuffy for their tastes, Virginia offers numerous design styles, from modern contemporary to Georgian to…prehistoric. At Enchanted Castle Studios in Natural Bridge, Virginia, a local artist has been credited with building the world’s most accurate replica of Stonehenge...in foam. Visiting this faux phenomenon may not feel as humbling as, say, trekking across the English countryside to see the real thing, but nonetheless, it’s a Virginian visionary marvel.

The Virgin Queen

Virginia was the sight of the first English settlement in the New World, and who better to name it for than England’s reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth I—the Virgin Queen. (The Latin word for virgin is virginius. “Virginia” is its feminine form.) The Queen’s nickname was not intended as a judgment of her character—though it does lend itself to some rather lurid historical investigation. Rather the use of the name Virginia seems to have been carefully considered by the Queen herself:

“Everything with this politic woman meant something. The permission to use her name was not mere coquettishness, not only the suggestion of romance which, genuine enough in that day, it has come chiefly to signify for us. It was, like everything with her, an intensely personal act, calling attention to an aspect of her personality which, if not unique in a ruler, was an unforgettable element in her fame. But it was also politics: a characteristically ambivalent notice to the world that she personally was involved as well as the Crown of England, her good name pledged. It was therefore an unmistakable underlining of her claim, which could not chivalrously be disregarded, a warning to others to keep off.”1

Was She or Wasn’t She?

The delicate question of whether or not Queen Elizabeth I was actually, technically and officially a virgin is to this day a matter of curiosity to historians, and the answer seems to be an unqualified “maybe.” Anyone who has seen the award winning 1998 movie Elizabeth can only conclude that the Virgin Queen was not only not a virgin, but that she carried on a very public and very sexual affair with Sir Robert Dudley, Lord of Leicester. An exquisite performance by actress Cate Blanchett notwithstanding, the movie is clearly based on extreme speculation and, even then, beautifully embellished.

To be sure, the Queen and Leicester, even in their own day, prompted—and even appeared to enjoy—widespread speculation about the exact nature of their relationship. But certain historical facts legitimize the possibility that Elizabeth truly was the Virgin Queen. Not the least of these is her own declaration: “...although I love and always have loved my Lord Robert dearly, as God is my witness, nothing improper has ever passed between us.”2 This statement is rendered more profound because it was uttered while she was sick with smallpox, and believed she was on her deathbed.3

Other convincing arguments have been made that Elizabeth certainly had the psychological profile of being extremely averse to the institution of marriage. Though a beautiful young woman at the time of her succession to the throne, and though that made her one of the most coveted and courted women in history, she may have been, at least subconsciously, deathly afraid of pregnancy and childbirth. Given the circumstances of her mother’s death (Anne Boleyn was beheaded when she “failed” to produce a male heir for her husband, King Henry VIII), and the death of her first stepmother a few days after giving birth to Elizabeth’s half-brother Edward, one can hardly blame her for having some severe, unresolved issues surrounding marriage and childbirth.4 And given that the only certain method of birth control in the sixteenth century was abstinence, the title of “Virgin Queen” begins to seem more likely.

A Close Call

The name Virginia was bestowed by Sir Walter Raleigh, a courtier, poet, and adventurer, who himself never actually voyaged to North America—some say because he was such a favorite of the Queen that she would not tolerate his absence for such a long period of time. Raleigh’s half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, was granted by the Queen the original patent for establishing an English colony in America, and upon his death in 1583 Walter Raleigh inherited that patent. Raleigh organized an expedition in 1584 led by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe which landed in July of that year on the coast of what is now North Carolina.

Amadas and Barlowe met Granganimeo, the brother of the local Indian chief or weroance, and attempted to communicate with him and his followers. This communication was, under the circumstances, fairly successful, except with regard to the name the natives used to refer to their country. “For when some of my people asked the name of that Countrie,” Raleigh would later write, “one of the Salvages (sic) answered Wingandacon.” The native, it turned out, had simply not understood the question, and so had replied with a polite, off-hand comment which was eventually translated as “You wear good clothes.”5

And so, until Queen Elizabeth I allowed her unofficial title to be applied to it, the first English colony in the new world was known as “Wingandacon.” The spelling took a variety of forms, including Wyngandecora, Wingantekoy, Wingane Dehoy and Wingan deCoy 6, but by the fall of 1584 “Wingandacon” began to appear in official English documents, as well as in those of the Spanish government, as the name of England’s potential first North American colony.

Virginia Dare

Just as Queen Elizabeth I bestowed her name upon the new country, so did the country bestow its name upon Virginia Dare, the first English child to be born and baptized in the New World. The baby Virginia was the granddaughter of John White, governor of the ill-fated first English colony on Roanoke Island. She was only a month old when White left his daughter, her family, and the other potential colonists at Roanoke to return to England for supplies.

Because of war with Spain White did not return to Roanoke for three years, and by then the colonists were gone, leaving precious few clues to their whereabouts or fate. The “Lost Colony” at Roanoke Island (which is actually in North Carolina) lives on as one of the most intriguing mysteries in American history. The name of Virginia Dare lives on also—as a part of that mystery, and as the very first American of English descent.

Motherhood

Despite the oxymoronic implications, Virginia is often referred to as the “mother” of the United States, given that it was this original colony that was divided and subdivided to create most of the other eastern states. But despite its status as “original” colony, Virginia was nowhere near the first state of the U.S. Not even close.

Largely because of the debate over slavery, and more specifically, how slaves would be counted for census purposes when it came to allocating seats in theHouse of Representatives, Virginia held off ratifying the Constitution until July 25th, 1788. That makes it tenth in the chronological list of states.

The debate that caused the delay was finally settled in favor of the “three-fifths” rule, which, while allowing slaves no rights as citizens, did count them as three-fifths of a person for census purposes. This ruling gave Virginia the largest original complement of Representatives in the House, thus it was apparently worth the wait for the “mother” of colonies.

To this day Virginia and three other states [1] maintain their status as “Commonwealths.” While there is technically no difference between this distinction and that of a state, the word connotes a government that is given by the “consent of the people” or for the “common wealth of the people” rather than by royal fiat. One wonders if Queen Elizabeth I would still give her consent…or her name.