VERMONT

I’m missing a place there’s no replacing

where she’s listening to crickets sing

I can only hear this TV humming

it’s dark in VT tonight

too bright in this fake light

—Caitlin Canty, Vermont

Pennies in a stream

Falling leaves, a sycamore

Moonlight in Vermont

—Margaret Whiting, Moonlight in Vermont

Maple Syrup and Teddy Bears

Vermont makes people think of maple syrup and quaint bed and breakfasts, which is appropriate because that’s what Vermont wants people to think. Maple syrup and tourism are two of the state’s biggest industries. In 2001, Vermont produced 26% of the nation’s maple syrup, more than any other state. They generated over half a million gallons of the pancake condiment—that’s more than a half gallon for every resident of the state...and production was way down that year.

Some other things come to mind when one hears the name “Vermont.” The state animal is the Morgan horse; a popular breed cherished by equine enthusiasts for its versatility and level-headedness. The Morgan Horse is also one of the earliest breeds developed in the United States. There are those who think of skiing, though that would be easterners. Residents of Colorado and Utah might have difficulty associating skiing with a state whose tallest peak rises no higher than 4,400 feet. Sometimes teddy bears come to mind, thanks to TheVermont Teddy Bear Company, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of the cute and cuddly stuffed companions. Still others might think of Vermont as a haven for progressive politics; certainly Vermont’s history was shaped by strong, independent-minded people who established a precedent in the state for breaking from the pack and forging new ground.

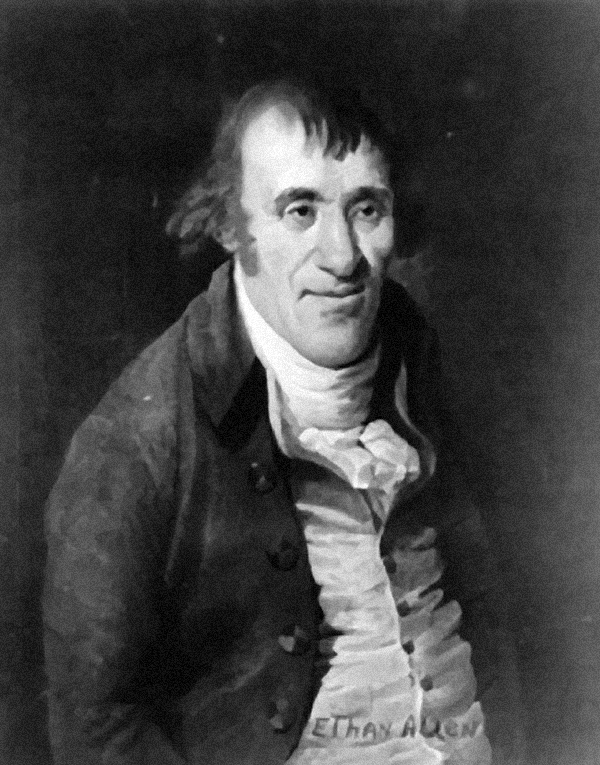

Benning Wentworth and Ethan Allen

But one does not have to reach far back into the historical consciousness to associate the name Vermont with the name Ethan Allen. Ethan Allen, the company, might be famous as a maker of fine furniture, but Ethan Allen the man has a slightly more nuanced reputation. Allen was the leader of the Green Mountain Boys, a band of men who fought not only for American independence from Britain during the revolution, but at about the same time fought for Vermont’s independence from New York and New Hampshire.

But Ethan Allen did not create Vermont. Had it not been for a nasty border war, Allen and his colleagues would probably have been quite content as citizens of New Hampshire or New York, which is what they believed themselves to be until around 1775. Credit for the creation of Vermont falls more appropriately to a man whose methods, upon closer review, were, like Allen’s—colorful, if not suspect.

Benning Wentworth, “an unscrupulous man who craved power, riches and pomp,”1 became governor of New Hampshire in 1741. In 1749 he began granting land west of the Connecticut River, even though the border with New York was being officially disputed. The first of these grants he rather audaciously named Bennington and set it on the west side of the Green Mountains—close to the New York border, as he saw it, but well beyond it by the measure of George Clinton, governor of New York.

By 1764, when the king confirmed that the land in question—between the Connecticut River and Lake Champlain—belonged rightfully to New York, Wentworth had granted 138 towns covering about three million acres and keeping about 65,000 acres for himself.2 Also known as the “Wentworth Grants,” they came to be more famously coined the “Hampshire Grants,” or simply “The Grants,” and were being aggressively settled.

Since many of the Hampshire grants overlapped grants made by New York, a series of ejection suits began to be filed by the “Yorkers.” In 1770, nine of them were due to be heard by the New York Supreme Court, and the Hampshiremen organized themselves for a legal fight. Known originally as the Bennington Nine, they elected Ethan Allen as their leader, and Allen went to Connecticut to hire a lawyer to defend them. The Bennington Nine lost the suits, due partly to a conflict of interest on the part of Chief Justice Robert Livingston, and afterwards Ethan Allen refused to accept a bribe by Livingston’s operatives to convince the Bennington grantees not to oppose New York’s authority. Allen’s refusal of this bribe proved to be a pivotal moment in the formation of Vermont.

Ethan Allen returned to Bennington and organized a band of about 200 men who called themselves the Green Mountain Boys. Their goal was to protect their land titles and to oppose—by force if necessary—the authority of New York. The exploits of the Green Mountain Boys are legendary and voluminous. What they wanted initially was to have their land grants confirmed to them, no matter which colony or state claimed jurisdiction, but by 1775 this seemed no longer an option. In that year Allen wrote a letter to the governor of Connecticut suggesting independence for The Grants.

Independence

Early in the American Revolution, Ethan Allen was captured by the British, leaving the Grants to continue their struggle without him. Embroiled in two wars for independence, The Grants’ residents decided in 1776 to form a “separate district,” and in their January 1777 Declaration of Independence, chose to call themselves “New Connecticut.” This name was quickly dropped, however, since a Pennsylvania community had already chosen the name for its own.

On April 12, 1777, a radical propagandist from Philadelphia named Dr. Thomas Young sent a letter addressed “To the INHABITANTS of VERMONT, a Free and Independent State, bounding on the River CONNECTICUT and LAKE CHAMPLAIN,” 3 urging them on in their fight for independence. Young, called by one historian “America’s first professional revolutionist,” also suggested that Vermont use as a model for its government the new federal Constitution which had been adopted in Pennsylvania. At the next convention of citizens of The Grants, a new constitution based on Young’s suggestion was adopted, and the name used by Young— Vermont —was also agreed upon.

By 1778 The Grants had declared independence, ratified a constitution, and elected a president of what they were calling the Republic of Vermont, and all this in the middle of the American Revolution. So brazen were the actions of the Vermont people that even some towns on the New Hampshire side of the Connecticut River requested, and were welcomed, to join them. Now the Green Mountain Boys were in conflict not only with New York, but with New Hampshire as well...not to mention with the British.

The tumult created by Vermont’s Declaration of Independence, and now, it would seem, territorial ambitions, continued until 1791. For the remainder of the Revolution the new republic’s destiny—whether as a state in the new United States or as a colony in the British Empire—was unclear. But by 1791 certain factors came together—primarily the agreement to terms with New York and the imminent acceptance of Kentucky as a southern state—to allow the Republic of Vermont to be accepted as the fourteenth state in the Union, and on March 4 of that year, it was.

The first state to enter the Union after the original thirteen colonies, Vermont paved the way for other new states to enter. Kentucky was accepted the very next year, and Ohio would enter as the first state to be created from the Northwest Territory in 1803. But as was the case for Kentucky and Ohio, the action of voting Vermont in as a state was a bit unorthodox, since the process of state admittance had not yet completely congealed.

Vermont was voted in by the U.S. Congress, and President Washington’s signature was, at that time, not required. The Act approved by Congress proclaims that, “…the said State, by the name and style of ‘the State of Vermont,’ shall be received and admitted into this Union.”

Okay, but why “Vermont”?

Dr. Thomas Young is generally given credit for applying the name “Vermont” to the fledgling state. To be sure it was after he suggested it that the name took hold, but why he suggested it is unclear. Tradition holds that the name had been in limited use to describe the region for years before Young used it, but there are differing (if not mutually exclusive) stories as to how it originated.

The one dating back the furthest is attributed to Samuel de Champlain, an explorer who first entered the region in 1609, lending his own name to the lake that marks the western border of Vermont. One popular book (and corresponding website) on state names asserts that “Vermont is an English form of the name that French explorer Samuel de Champlain gave to Vermont’s Green Mountains on his 1647 map.”4 This assertion is attributed to a Smithsonian report from 1955 written by John Harrington, and has been widely proliferated in books and on hundreds of websites. But while Champlain may well have noted the Green Mountains on a map, he certainly did not do so in 1647, because he died in 1635.

In his excellent bicentennial history of Vermont, Charles T. Morrissey describes the most colorful and probably most famous story of the origin of the name. It involves an Anglican clergyman named Reverend Samuel Peters who published his own account of the tale in 1807. Peters claimed he was traveling through the region in 1763 performing baptisms, when he decided to baptize the entire state.

“Peters...and his party in the late fall ascended “a high mountain, then named Mount Pisgah, because it provided to the company a clear sight of Lake Champlain at the west, and the Connecticut River to the east, and overlooked all the trees and hills in the vast wilderness at the north and south.” While pouring a bottle of spirits on a rock he dedicated the wilderness with “a new name worthy of the Athenians and ancient Spartans—which new name is Verd Mont, in token that her mountains and hills shall be ever green and shall never die.”

Peters, however, was known for telling lies, and his tale was largely disbelieved, despite his fierce defense of it. Morrissey continues:

“Peters insisted that his claim was valid, and he insisted that he named the state Verd Mont, for Green Mountain, not Vermont, which translates from the French as “Mountain of Maggots.” Piqued at his critics he curtly observed: “If the former spelling is to give way to the latter, it will prove that the state had rather be considered a mountain of worms than an ever green mountain!”5

While some history books claim that the phrase “Verd Mont” was in use well before Peters claimed to have conferred it, they offer no specific written reference. Technically, it is not even proper French. “Green mountains” stated correctly would be “monts verts,” which does not easily morph into “Vermont.” But the two French words, whoever applied them, are certainly the ones which formed the state’s name. Perhaps the person or people who first used them were not native speakers of French.

Morrissey writes that the matter was complicated by the discovery of a 1774 map of Sherbourne, Vermont. It shows Killington Peak, the second highest mountain in the state, labeled “Mount Pisgah.” Atop this mountain, on a clear autumn day, one is in fact able to see both Lake Champlain to the west and the Connecticut River to the east. Perhaps, Morrissey concedes, Peters was telling the truth after all.

End Notes

1. Robertson, Doug, “The Story of Ethan Allen (1738-1789), A Right to Liberty,” From Revolution to Reconstruction...and What Happened Afterwards, http://odur.let.rug.nl/~usa/B/allen/allen01.htm, Last updated 3/6/2003, retrieved 7/30/09

2. Morrissey, Charles T., Vermont: A Bicentennial History (New York, 1981), p.71.

3. Wardner, Henry Steele, The Birthplace of Vermont: A History of Windsor to 1781 (New York, 1927), p. 357.

4. Shearer, Benjamin F. and Barbara S., State Names, Seals, Flags, and Symbols (Westport, Connecticut; London: Greenwood Press), p. 16.

5. Morrissey, p. 70.