UTAH

Then the lord called down to Brigham, said “I got a great idea —

I want a mighty city and I think I want it here”

Well, Brigham kicked a prairie dog and muttered in his beard

Said, “You’ve put me through some changes, Lord, but this one’s really weird”

—John Barlow & Bob Weir, Salt Lake City

On a rattlesnake speedway in the Utah desert

I pick up my money and head back into town

—Bruce Springsteen, Promised Land

Mormons

Whereas with some states we find our perceptions and impressions to be wrong, exaggerated, or overly stereotypical, the association of Mormons with Utah would be difficult to overstate. (No pun intended. Okay, maybe a little bit intended.) Over seventy percent of Utah’s population is Mormon. The state’s symbol, the beehive, is derived from the Book of Mormon and is said to signify work and industry. Nearly all of the state nicknames—“The Deseret State,” “Land of Saints,” “The Mormon State,” refer to the church and its liturgy. Utah’s history is very much the history of the Mormons, and Utah’s present reality is Mormonism.

At times, it seems, the affiliation of the Latter Day Saints with Utah is downplayed for political reasons. The connection of a religion, particularly one that is often characterized as “cultish,” to such a secular entity as a state, is distasteful to many Americans. For those people the struggle with “separation of church and state” could not find a more poignant battlefield than Utah. In Utah the Mormons are in control—of the Church and of the State. For some it is galling, but for most, within and without, it is simply the way it is.

Still “Utah” can mean other things to people: spectacular canyons and rock formations, the Great Salt Lake, Zion National Park, and awesome skiing. It’s the heart of the American West, still something of the untamed wilderness toward which the Mormons directed their pilgrimage, and still very much a land of the Indians.

But Briefly...

By the 1840s the carving up of the American West into individual states was practically inevitable. To some extent the Mormons knew this, and proceeded accordingly. The emigration of Mormons to the Great Salt Lake region was calculated, organized, and controversial. They were led by Brigham Young, heir to Joseph Smith’s congregation, and they believed that they would settle in an area that would one day exist within the United States. The storied history of Mormonism, while important to the creation of Utah, is well-documented, voluminous, and plagued with controversy, and it need not be detailed here. However, some details about the evolution of Mormonism help explain the creation−and the naming−of Utah.

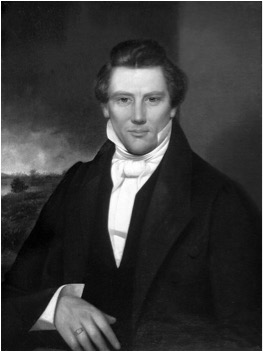

In 1844 Joseph Smith, Jr., the founder of the congregation, was brutally murdered along with his brother, both shot to death by Church antagonists while locked in a Carthage, Illinois prison cell. Smith’s alleged crime was that he had vandalized the printing facilities of a local newspaper that routinely printed anti-Mormon stories, though the official charge against him was treason.

Shortly after Smith’s murder Brigham Young, formerly one of several leaders among the Mormons, emerged as the new President of the Church, and in 1847 led approximately 16,000 followers out of the Mississippi Valley to the Great Salt Lake in what was then commonly referred to as Eastern California. The region was controlled by Mexico but coveted by the United States, and the two countries were embroiled in a war which would decide the political destiny of western North America. With the emergence of Manifest Destiny there was every reason to believe that all of the continent north of the Rio Grande would soon come into American possession one way or another.

In Great Salt Lake City, the Mormons founded a thriving colony that was governed by the Church in religious and secular matters. The success of the colony has historically been attributed both to its brand of communal enterprise, as well as its isolation in the desert, but this isolation would last only long enough for them to become well established. On February 2,1848 the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which ended the war and gave to the U.S. what is commonly called the “Mexican Cession,” which included parts of Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona, and all of Utah, Nevada, and California. Almost simultaneously, on January 24th of the same year, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California. These two events had the effect of ending the isolation of the Mormons, as thousands of people moved west to seek a quick fortune in gold.

The Mormons knew that eventually they would have to deal with a federal government, either American or Mexican, but Brigham Young and the Church leaders were divided on whether or not to immediately petition Congress for territorial status. Young’s nephew wrote in October of 1848 “...If we send a written petition there, we may expect that some sycophant of an office seeker will...take from us our rights as free men.”1 Congress too, was ambivalent for a while about organizing portions of the ceded territory, tabling a motion to do so on January 3, 1849 (2). But in May of 1849 the Mormons did send a petition asking Congress for recognition as a territory.

The State of Deseret

“Deseret” was the name the Mormons chose for their new territory. It is taken directly from the Book of Mormon,

“And they did also carry with them deseret, which, by interpretation, is a honeybee; and thus they did carry with them swarms of bees...”

The borders of the land they requested were enormous, including all of “Eastern California”: virtually all of present day Utah and Nevada, almost all of Arizona, about half of Colorado, southern California including San Diego which was to be their seaport, and corners of New Mexico, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon.

The petition for territory status, however, was never presented to Congress. Before the Mormon delegate had the chance, the Church leaders changed their minds again and decided to try a different method. They would organize their own state government (much of which was already in place), and then ask for admission to the union as a fully formed state. Their reasons were fairly pragmatic. Territories relied upon the federal government to appoint most of their officials—including their governor—and to create many of their laws. The Mormons were adamant that they retain control of the community they had founded, that they be able to elect their own governor, and create their own laws. They drafted a constitution, elected a governor (Brigham Young) and a General Assembly, and declared themselves the provisional state of Deseret in July of 1849. Then they sent another delegate to Washington who would work with the original delegation to try to achieve statehood for Deseret.

Sentiment in Washington ran the gamut. There were those who fully supported the Mormons, either defending or ignoring the obvious religious influence on such a large tract of land. But there were also some who were vehemently opposed, not only for the religious reason per se, but for the practice of polygamy which was ubiquitous in the Mormon community. Those in the middle had concerns about allowing the religious group to dictate territorial policy, but admired the Mormons’ fortitude, and were, to some extent, grateful at the prospect of an American foothold in a land they had just fought a war to gain possession of, a land admittedly unattractive to most other settlers.

For the Mormons some form of governmental organization was becoming necessary. The miners headed for California were pouring across the American West, and the Salt Lake community was now a midway point for the flood of prospectors on their way to the gold fields. The Latter Day Saints found themselves in the precarious position of wanting federal authority over the intruders, but not wanting to remove their own church authority. What they really wanted was the federal legitimization of their own self-imposed, religious government.

But that wasn’t likely to happen. The Mormons were not a litigious society. Their church bishops presided over civil matters in the same capacity as judges and juries. That was a system that the U.S. Congress simply could not sanction. Also the prospect of having any governor imposed upon them was unthinkable to the Mormons. They wanted Brigham Young, and would accept no other.

“Utah”

The Smithsonian report on state names of 1954 asserts that the name “Utah” is derived from the White Mountain Apache word “Yuttahih.” The Apache used the word to refer to the neighboring Navajo Indians3. The report explains that the word means “one that is higher up” and that the Navajo did indeed live at a higher elevation than the Apache, but that the Spaniards who learned the word mistook it to refer to the Utes who lived still higher.

While most references define “Utah” as “those who live higher up,” “mountain people” or something similar, others insist that the name actually means “meat eaters,” and still others, “Land of the Sun.” Some believe the word is derived not from the Apache language, but from Navajo, or even from the Ute language itself. This last assertion is unlikely. The Ute name for themselves is “Nuche” which, like most self-references of native American tribes, simply means “the people.” While the actual definition and derivation of the word is somewhat disputed, what is certain is that it was first recorded by Spanish missionaries who explored the area in the late 1770s, and wrote it as “Yuta” or “Yuutaa.” Settlement of California by the Spanish, and indeed the Mexicans after they won their independence, was limited almost exclusively to the west coast of the continent, so until the Americans became interested, the name “Utah” was almost unknown, and rarely applied to any specific region. In the 1820s William Ashley and Jedediah Smith, two of the earliest pioneers of the region, explored much of northern Utah, and came into contact with what Ashley called the “Eutaw” Indians, engaging in trade with them. Largely through the efforts of Ashley and other traders/explorers the name became more prominent on maps of the west.

By 1850 the territory-creating machinery in Congress was in motion and would not be derailed. Congress considered it their duty to organize the Mexican cession without regard to the Mormons’ request, but in the end the Latter Day Saints gained a modicum of satisfaction through their efforts in Washington. Dr. John M. Bernhisel was the chosen lobbyist for the Mormons, and he worked tirelessly to convince even the most antagonistic congressmen to legitimize their government.

It was Thomas Hart Benton, Bernhisel reported, who “disliked the name of Deseret , which to him was repulsive [Benton was an outspoken opponent of the Mormons] and sounded too much like Desert.” Stephen Douglas, although a supporter of the Mormons, agreed and preferred the name “Utah,” saying he would insist on that name for any new state or territory. Douglas also suggested that the massive borders for the provisional state would never be acceptable to Congress, and suggested they be curtailed.

The Organic Act for the Territory of Utah was passed September 7, 1850, and President Millard Fillmore signed it two days later. While substantially smaller than Deseret, Utah was still quite large, including the current states of Nevada, Utah, half of Colorado, and a small part of Wyoming. On the questions of the name and the borders, the Mormons submitted their “quiet acquiescence...for the time being” and were satisfied by having their own slate of nominees accepted into key government positions, i.e., they got Brigham Young as their governor.

Still, the Mormons were not happy about the name change:

“The congressional liking for the name of Utah was not shared by the inhabitants of Deseret... Utah was one of the several forms of the name for the Ute Indians, who were regarded by the mormons (sic) with a little fear, more pity, and a great deal of contempt.”4

As far as the federal government is concerned, that was the end of Deseret. But the Mormons were not entirely satisfied with their lot. They were indignant that California, with a much smaller white population, was admitted as a state. Bernhisel wrote to Brigham Young, “Should not a nation...cherish those who are endeavoring to render her most sterile and barren domain productive.”5 The next few years saw several attempts at petitioning Congress for statehood, but the federal government, now embroiled in issues that would lead to the Civil War, would not be bothered by the pleas of this religious “sect” whom many in Congress disliked and distrusted.

The War and the end of Deseret

Specific events led to serious conflict between Utah and the federal government, but more generally there was a clash of philosophies. The Mormons who had settled the region believed it their right and duty to govern themselves, while Congress and the President assumed the duty was theirs. It was, in its purist form, a state’s rights issue, a question of republicanism versus federalism, the same differences in governmental philosophy that divided Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton almost one hundred years earlier, a difference that the United States still struggles with to this day.

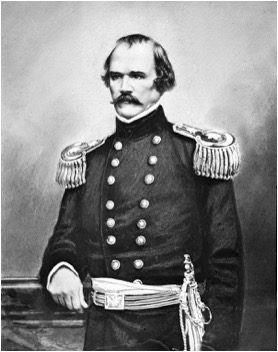

But the religious aspect of it, while a common theme in American colonization, muddied the waters on both sides. The Mormons had moved to Utah not only to enjoy freedom of religion, but to allow themselves to be governed by their church. The U.S Congress saw this as a usurpation of federal authority, the Mormons as freedom of religion. Under these conditions a conflict was almost inevitable, and it came in the late summer of 1857. Dissatisfied with the “dictatorial” leadership of Brigham Young, and appalled at the Mormons’ practice of polygamy, in 1857 the president sent Colonel Albert S. Johnston into the territory to establish a new territorial government. Bracing for an “invasion by a hostile force” the Mormons attempted (and succeeded to some extent) to stall Johnston’s progress into Salt Lake City by burning some of their wagon trains full of supplies. This defiance of the U.S. Government is often referred to as the “Mormon War,” and it culminated in the grisly Mountain Meadows Massacre in which almost a hundred settlers from Arkansas and Missouri were viciously murdered.

The people of Utah reluctantly accepted Johnston’s imposed government, and a new peace followed. But the Mormons still held out hopes for Deseret. In 1862, they called a constitutional convention, and elected a general assembly for the “State of Deseret.” Sometimes called the “Ghost Government of Deseret,” this body was unprecedented, and would never be replicated in any other state. It was a second legislature, and a second governor (Brigham Young), whose main function was to echo to the inhabitants of Deseret the laws and provisions which were passed by the territorial legislature of Utah. In this way the Mormons asserted their own control over themselves, while not stepping on any federal toes. In the meantime, requests to Congress for statehood continued. This ghost government met yearly until 1870, when it rather mysteriously ceased to exist.

Deseret’s Last Stand

Still lobbying for statehood, Utah’s borders had been squeezed to their current boxy shape by 1872. In that year its citizens held a constitutional convention to try to further their progress in achieving statehood. By this time there were many Mormons who wished to move on. They wanted statehood that was sanctioned by Congress and the president, rather than their own ghost government. They set about addressing the real sticking points, the biggest was the issue of polygamy, but also being debated was the name.

Those who favored changing the name from Deseret to Utah in their own constitution argued “...the name Deseret might be made a basis of prejudice by persons opposed to the State movement.” These were sage words, indeed, for the Mormons had enough obstacles to overcome in convincing Congress to grant statehood. The polygamy issue alone alienated a majority of the congressmen to the prospect. The name Deseret was entirely associated with Mormon liturgy, and that fact alone would likely make it distasteful to Congress, no matter how euphonious it was.

Opponents of the change, on the other hand, argued that the name Deseret was entirely unobjectionable, was dear to the petitioners, and was easy to spell, unlike “Utah.” This last point is debatable, but was a common argument for many a name proposed for a territory or state. In a vicious attack on the alternative, opponents argued that Utah “...referred to a dirty, thieving, insect-infested, grasshopper-eating tribe of Indians.”6 But the argument that Deseret was better because it did not originate with an indigenous tribe was counterintuitive. Congress routinely used aboriginal names in their creation of territories and states, and were hardly likely to change that pattern in favor of a name with a clearly religious slant.

One delegate recommended a new name, “Argenta” referring to a chapter of Masons in Utah, but in the end the delegates voted to retain “Deseret.”

For Congress the problem of Utah was a sticky one. The residents wanted and needed statehood because the territorial system was simply not sufficient. Court cases were piling up for lack of judges, and the people could not legally appoint their own. Meanwhile, the population continued to grow. The problem was not the name (Congress had no intention of replacing the name Utah with Deseret), but polygamy was an absolute show-stopper. Until the proposed state constitution included a full condemnation and outlawing of bigamy and polygamy, Congress would not even consider statehood.

The polygamy issue so consumed the efforts to become a state that the name issue faded from the public debate. By 1896 both issues had finally been decided. Polygamy was against the law, and the name of the state would be Utah . On January 4th of that year President Grover Cleveland at last made Utah the 45th state of the Union.

End Notes

1. Morgan, Dale L., The State of Deseret, (Logan, 1987), p. 25.

2. Morgan, p. 25.

3. Harrison, Clifford Dale, The Explorations of William H. Ashley and Jedediah Smith, 1822-1829 (Lincoln, 1991) p. 386.

4. Morgan, p. 82.

5. Morgan, p. 85.

6. Morgan, p. 113.