TEXAS

The stars at night

are big and bright

(clap, clap, clap, clap)

deep in the heart of Texas

—Deep in the Heart of Texas

There’s a yellow rose in Texas,

I’m goin’ there to see

—The Yellow Rose of Texas

Big State, Big Pride

Few states can be caricatured like Texas. Just choose your stereotype: oil wells, cowboy boots, NASA, country music, small towns, big hair, funny accents, tumbleweed, the Alamo, barbecue. From King of the Hill to True Stories , from Walker—Texas Ranger to Giant , Texas provides television and movies with a perfect setting for the outrageous, the obscure, and the unbelievable. As Bugs Bunny puts it while watching carrots spew from an oil derrick, “Anything can happen in Tex-ayuz.”

Like those of the more populous states, namely New York and California, the name “Texas” evokes emotion and passion at its very utterance. But unlike the others, there is very little hint of sophistication or of the cosmopolitan with Texas. Say “New York” or “California,” and one can immediately understand—though not necessarily sympathize with—the allure, the magnetism that attracts all those millions of people who choose to make those states their home. It is something about the excitement, the opportunities, the modernity. But the name Texas inspires no such excitement. It instead seems to exude a quaintness, an aw-shucks down-hominess that to some is comical and unappealing, but to others is inviting, warm, and attractive.

For native Texans, the pride in their state is possibly the fiercest in the land. Texans wear popular t-shirts emblazoned with the Lone Star flag and the word “Secede” underneath (even before Governor Rick “Good-Hair” Perry made his famous threat of secession regarding the 2009 economic stimulus package). The study of Texas history is mandatory in the state’s schools, taught even before that of the nation. There is a downright haughtiness in the twangy Texas accent which sounds, at its thickest, laughable to the ears of a Yankee but is imperceptible to another Texan. From the food—be it barbecue or Mexican—to the music—be it live rock and roll or country music on the radio—to the cowboys—both real and wannabe—Texas is nothing if not proud.

This state pride has an interesting quirkiness. One of the features for which Texans exude a fervent pride is the state’s size—Texas has more land mass than any of the other contiguous states. (One can imagine the collective sinking of hearts when Alaska joined the Union.) This makes for an incredibly diverse geography, not to mention population, and a befuddling question about that passionate Texas Pride.

Consider...

• East Texas: Covered in pine trees and dotted with lush forests and lakes, this region of the state is populated much like its neighbor Louisiana. A large African-American population connects East Texas with “the South” and all of the antebellum, plantation-owning, civil-rights-fighting images that the South conveys.

• Metropolitan areas: Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, among others offer a legitimate “big city” feel and a genuine cultural diversity inherent in such urban areas.

• Central Texas or the “hill country”: often associated with George W. Bush, even though he grew up in New England and only purchased the Prairie Chapel Ranch near Crawford in 1999, when he was running for president.

• South Texas: Brownsville and all along the border with Mexico has a large Latino presence, and given that Texas’ history is so closely associated with that of Mexico, this is not surprising. While the image of “illegal aliens” is difficult to overcome, it is, in the case of south Texas, largely erroneous. A population that may be called Latino, because they speak Spanish and have dark skin and eyes, actually have lived in south Texas since long before it became an independent republic in 1836.

• The gulf coast islands: Legitimate tropical sandy beaches with blissfully warm gulf waters and plenty of vacation homes and condo-filled resort towns for Spring Break crowds.

• West Texas: decidedly “oil” territory, and the Panhandle, often pictured as barren and deserted, is actually quite productive farmland.

• Austin: the “jewel” of Texas, famous as the live-music capital of the world, and the state’s politically progressive haven. Austin, the state capital, is home to the University of Texas as well as more than six other colleges and universities.

So the question must be asked, what is it that Texans are so proud of? Is it the thick piney woods of the east or the tumbleweed deserts of the west? Is it Padre Island or Dallas? Is it the ethnic diversity or the football teams? Whatever it is, it exists only within the borders of the state, and any Texan will tell you that you just have to be born there to understand.

The Indians and the Spaniards

The word “texas” (tejas, tayshas, texias, techan, teychas—like many state names, there were dozens of different spellings before one emerged as dominant) was used by the Hasinai Indians who inhabited a small section of East Texas in the mid-1500s when the Spaniards first made contact. The Hasinai spoke a Caddoan language (a derivative of the Sioux language family) and were among the more socially advanced tribes of the area1. The word “texas” meant “friends” or “allies,” and the Hasinai used it to refer to several other tribes in the area who were friendly to them and loosely organized against the Apaches to the west.

They also used “Tejas!” as a greeting “Hello friend!,” so the possibility that it was the first word heard by any European from natives of this region is not far-fetched, though it is not clear when the Spaniards first heard the word uttered. Cabeza de Vaca had wandered through much of Texas and near the villages of the Hasinai during his seven-year trek (see Mississippi), ending at Culiacan in 1536. Then in 1542, what was left of Hernando de Soto’s expedition after their leader’s death explored a section of East Texas in an attempt to find a route back to Mexico. It is not clear if any of these explorers encountered the Hasinai or heard the word “Tejas,” but it would be over a century before the word was recorded and applied to the region it now names.

It is certain that the greeting “Tejas!” was made when the Hasinai were met by a group of Spaniards led by an explorer named Alonso De León and a missionary, Father Damián Massanet. They had gone into the area of the Sabine River in 1689 to determine the extent of French encroachment into what the Spaniards considered to be New Spain. The Spaniards were looking, in particular, for Fort St. Louis, the ill-fated settlement established by La Salle on the Texas coast, which had been destroyed and most of its inhabitants killed by Karankawa Indians. It was Massanet who recorded the word “Tejas” in his report, erroneously using it as the name for the Hasinai Indians.

This was a confused translation. “Tejas” was the word the Hasinai used for their friends and allies. Hasinai, meaning “the people,” was how the natives actually referred to themselves. But in what would become a pattern of misunderstanding between Native Americans and Europeans, the Spanish used “Tejas” to refer not only to all of the regional tribes but to the land as well. The extensive Handbook of Texas Online describes how another Spanish missionary, Francisco de Jesus Maria, attempted to correct the Massanet translation. It explains that the natives of that region did not constitute a “kingdom” as Massanet had reported, did not call themselves Tejas but Hasinai, and that the tribal leader whom Massanet had referred to as “governor” was not a head chief. The Spaniards attempted to integrate these corrections into their official documents, but the name “Tejas” had been fixed upon the maps and did not fade easily. The Spaniards continued to refer to the region as the “Empire of Tejas” and considered it part of Mexico in New Spain.

The Spanish Province of Tejas

During most of the 1600s, Tejas was a mysterious region to the Spanish, as it represented the furthest reaches of Mexico, the frontier of their domain, but not worth settling unless it was in danger of being occupied by another European nation. We don’t want it, but we don’t want anyone else to have it either was a common theme among the powerful European nations with regard to the two continents they had stumbled upon. From 1690 to 1693, the Spanish attempted to build missions in the land of Tejas in order to keep an eye on the encroaching French, but disease and Indian hostilities forced them to abandon the region. They burned their buildings, scoped out the area to make sure the French weren’t horning in, and left, noting for future attempts that colonists and fortified presidios must accompany any efforts at settlement in Tejas.

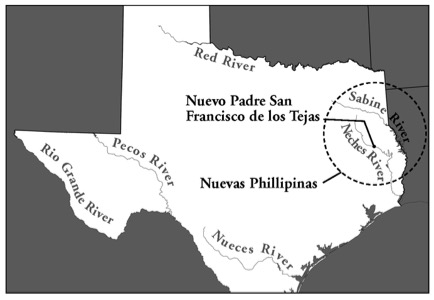

In the early eighteenth century, during a lull in hostilities with the French, Spanish missions began to spring up along the Neches River in east Texas, one at “a point almost within cannon shot of the French outpost at Natchitoches on the Red River.”2 One of the missions was named Nuevo Padre San Francisco de los Tejas, but Spain had applied a more official name to the province: “Nuevas Phillipinas” in honor of the Spanish King, Phillip V. These missions constituted Spain’s still rather tenuous hold on the region, and even though some maps recognized its new name, the most common label was still “Tejas.”

With the renewal of hostilities came a French invasion sometimes referred to as the “Chicken War.” During the French capture of the first Spanish mission, as the story goes, the loud squawking of excited chickens produced enough mayhem to allow the escape of a Spaniard layman who was then able to warn the other missions of the approaching French, allowing them to evacuate. Two years later, however, the Spanish—under San Miguel de Aguayo—retook the missions with authority, supplying them with new troops and colonists and asserting a powerful presence which did not go unnoticed by the French. For his efforts Aguayo was named governor of the newly created Spanish “Province of Tejas.”

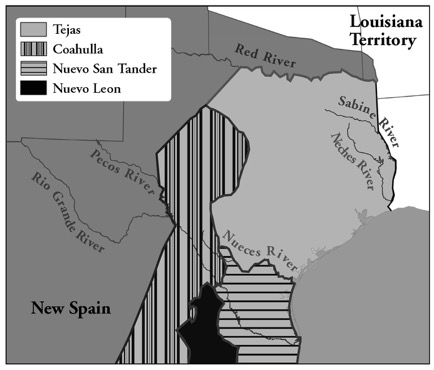

While the rest of North America was busy with the American Revolution, the Spanish were eagerly colonizing Tejas. Thousands of settlers moved into the region, the northern border of which was, vaguely, the Red River (though Spain claimed virtually all of western North America after France ceded Louisiana to her in 1762). The southern border of the province of Texas was the Nueces River, not the Rio Grande. This division was affected by José de Escandón, a tireless colonizer of the region, who named the province south of Texas Nuevo Santander after his home province of Santander in Spain. The area between the Nueces and Rio Grande Rivers was less heavily populated than either Texas or southern Nuevo Santander, though the region, commonly called the “Nueces Strip,” would eventually be bitterly disputed by the U.S. and Mexico. Western Texas was part of the Mexican province of Coahuila but was, and still is, sparsely populated.

Anglo Colonization

After the American Revolution, U.S. citizens began moving into Texas, many with political ambitions and dreams of seeing Texas become a U.S. dependency. To that end, they fought largely on the side of the revolutionaries during Mexico’s War for Independence from Spain, which began in 1810. In 1812 a revolutionary commander named Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara helped drive the Spanish from Texas, and on April 17, 1813, he declared Texas an independent state which formed “a part of the Mexican Republic to which it is inviolably joined3.”

Well perhaps inviolably but not, as it turns out, permanently. The state lasted only four months, after which the Spanish authorities, who took back power, began a form of ethnic cleansing designed to drive all Anglo-Americans out of Texas.

It was around this time that the pronunciation of the word “Texas” began to change. The “x” in the name is an artifact of the Spanish language (that is, the language of Spain, as opposed to that of Mexico). The same sound was produced by the Mexican “j”, one of the differences between the two closely related languages. Europeans saw “Texas” on early maps created by the Spanish, and would have pronounced it Teks-uz, even though the Spanish pronunciation was Tay-hoss. It is clear that the pronunciation followed the original Spanish spelling, and only when the Mexican language morphed was the “j” commonly inserted in place of the Spanish “x”.

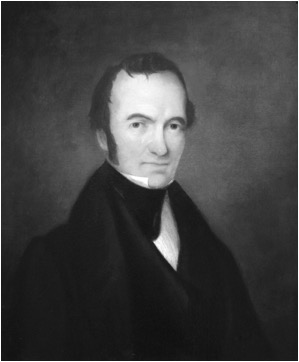

Despite Spanish efforts, the flood of U.S. citizens into Texas would not be stopped. Unable to stem the tide of immigrants, in 1820 Spanish officials opened Texas up to any “foreigners” who would respect the laws and constitution of the monarchy. An American colonizer, Moses Austin, asked the viceroy in San Antonio for permission to plant a colony of 300 American families in Texas. A former “subject” of Spain, as he had previously lived in Spanish Missouri, Austin was supported by friends in the Spanish government. His request was granted, but when he died shortly before the colonists were set to begin their journey, his son, 27-year-old Stephen, had to assume his leadership role and continue the effort without him. Unfortunately for Stephen F. Austin, not only did he have to prove his legitimacy as heir to his father’s claim, but when, in the summer of 1821, Mexico finally won her independence from Spain, he had to renegotiate that claim with the new government. Both of these he did successfully, and the winter of 1821 saw the beginnings of his massive colonizing effort. Other colonizers or “empresarios” also brought Anglo-Americans to Texas, but none were as successful as Austin.

In 1824 Mexico combined the old Spanish provinces of Coahuila and Texas into one Mexican state with the cumbersome—if obvious—name of “Coahuila-Texas.”

The Republic of Texas

The movement for Texas independence began with the Fredonian Rebellion of 1825-26. Haden Edwards was an empresario who angered Mexican officials by demanding that settlers who already occupied land in the section of east Texas that Mexico later granted to him either move out or pay him for their land. This was a clear breech of the Empresario Agreement, but Edwards forced the issue. When the government officials attempted to censure him, he declared his territory, which included the city of Nacogdoches, an independent republic called “Fredonia.” Edwards attempted unsuccessfully to gain allegiance from the native Cherokee Indians but did get support from the settlers he had brought with him and from a few other Anglo settlers in the region. When eventually faced with Mexican troops, Edwards fled to the United States, but the incident polarized factions in Texas and made the Mexican government suspicious of Anglo colonizers.

Another issue that began to divide Anglo-Texas from Mexico was slavery. On September 15, 1829, Mexican President Vicente Guerrero issued a proclamation of emancipation for all slaves. The edict was barely noticed in most of Mexico where the practice was virtually non-existent, but in Texas it caused such an uproar that the state was excluded from the proclamation, and slavery continued.

The following year, the Mexican government, so alarmed at the enormous number of immigrants to Texas from the U.S., created the Law of April 6, 1830, which stated that “Citizens of foreign countries lying adjacent to Mexican territory are prohibited from settling as colonists in the states or territories of the Republic adjoining such countries.” While this outwardly prohibited colonization in Texas by Americans, and did slow its rate, loopholes were found, and often the law was simply ignored. And so still the Americans came to Texas.

Meanwhile the U.S. government, under Presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, were openly coveting Texas. Adams asserted that the Louisiana Purchase extended south all the way to the Rio Grande River, and both presidents offered money to Mexico to negotiate a “more suitable” boundary for the U.S. The monetary offers were declined, but the overtures compounded the suspicions of the Anglo colonists by the Mexican government.

Finally, in 1835, the citizens of Texas revolted and began to form their own independent government. The Texas Revolution was relatively short, lasting only about seven months. The Mexican army suffered about 1500 casualties, while Texas lost some 700 souls, including virtually all of those fighting the famous and futile battle of the Alamo. The war ended with the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. This final showdown was actually a surprise attack perpetrated by Texas General Sam Houston on Mexican President Santa Anna’s forces as they took their afternoon siesta, and it famously lasted only eighteen minutes. During the battle, Santa Anna disappeared and was immediately sought by the victorious Texans:

“Santa Anna shed his ornate uniform to elude discovery. It was not until he was saluted as “El Presidente” that suspicion was narrowed. Unfortunately for Santa Anna, it was well known that he wore silk underwear. So, when it was discovered that this same person who had been saluted was also wearing silk underwear, the Texans knew they had captured Santa Anna4.

Annexation

There were—and are—many who believe that the revolution was a conspiracy by Texans to wrest the state from Mexico in order to deliver it to the United States. Many Texans were open about their desire for annexation to the U.S., and the government of the new Texas Republic, led by President Sam Houston, wasted no time in voting to request that annexation. But the process was delayed somewhat, in part because treaties between the U.S. and Mexico hindered it.

Finally, however, on February 29, 1845, after an existence of almost ten years, President James K. Polk signed the legislation annexing the Republic of Texas as the 28th state in the Union. Upon entry, this newly acquired land included parts of Oklahoma, New Mexico, and a sliver of Colorado. In 1850 Texas agreed to sell to the U.S. the lands north and west of its modern-day borders for the sum of $10 million. The northernmost border of Texas lies at 36 degrees, 30 minutes, the line that had previously been established by the United States as the border between slave and non-slave states. Only about fifteen years after entering the Union, Texas would secede from it with the rest of the South during the Civil War.

A little known (outside of Texas) provision of the annexation agreement of 1846 gave the state the right to divide into as many as five smaller states. This was considered a possibility just prior to the Civil War in order to give the South more votes in the Senate. The reality, however, was that much of northern Texas sympathized with the North, and the plan may have backfired, so it was never undertaken.

To this day the state claims the right to divide itself, and there have been outspoken proponents of doing so, citing the state’s huge size as well as geographical and cultural differences. Even today, newspaper editorials and web articles advocate the so-called “Great Divide,” or the division of Texas into five smaller states. Most of these writings are tongue-in-cheek, but occasionally a serious suggestion is made, usually by someone mad-as-hell at the federal government. These calls for division are virtually always viewed as an empty threat rather than an actual proposal, as was the statement by Governor Perry mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. Given Texas pride and tradition, it seems an unlikely scenario. Still...you have to wonder what they might call these new states.

End Notes

1. Magnaghi, Russell M., “Hasinai Indians,” The Handbook of Texas Online, http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/HH/bmh8.html, 2/23/02.

2. Richardson, Rupert N., Adrian Anderson, Earnest Wallace, Texas: The Lone Star State, 7th ed.(Upper Saddle River, 1997), p. 29.

3. Richardson, et al, p. 52.

4. “Battle of San Jacinto,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Battle_of_San_Jacinto&oldid=224147615, Date of last revision: 7 July 2008, Date retrieved: 12 July 2008.