TENNESSEE

Oh, Oh Tennessee Me

Tennessee Me see me loving you

See me by the fire side light

Come and see me through the night

Tennessee me through the night

—Secret Sisters, Tennessee Me

Oh remember my darling when spring is in the air

And the bald headed birds are whisp’ring ev’rywhere

You can see them walking Southward in their dirty underwear

That’s Tennessee Birdwalk

—Jack Blanchard and Misty Morgan,

Tennessee Birdwalk

Middle?

Geographically Tennessee is divided into three sections: East, West and Middle, and Tennesseeans aren’t the only ones who know this. It is part of the state’s geographical identity. But when you think about it, no other state has such a well-defined “middle.” Almost all have “Norths”, “Souths”, “Easts”, or “Wests”, or some combination of these directions, and some large states like Texas and Montana have “Centrals,” but even the other long, thin states like Florida and California don’t refer to their central regions as “middle.” Tennessee does.

These three divisions, while seldom delineated on maps, are almost as important to people of the region as the delineation between the states themselves. One state history book asserts it this way:

“Tennesseeans...seldom identify their home state by its name alone. Their usual response: ‘I live in West Tennessee,’ or ‘My home is in Middle Tennessee,’ or ‘I’m from East Tennessee.’ This is no idle conversation gambit...It is a statement of geography which is also a condensation of history, a reminder of sociology, a hint of cultural variety shaped by geographical fact...”1

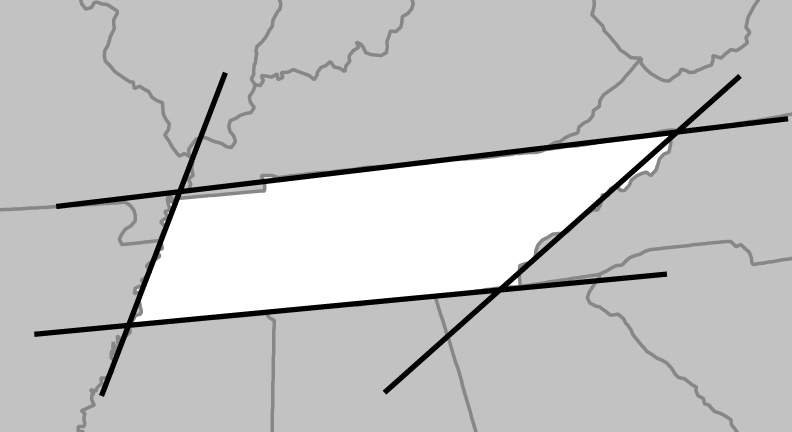

Looking at Tennessee on a map forces you to remember your geometry. Is it a trapezoid or a parallelogram? Whatever it is, it is almost four times as long as it is wide—432 miles by 110 miles—with unnaturally straight lines on the north and south, and roughly parallel diagonal rivers marking the ends. It looks a little like Kentucky was plopped on top of it and squashed it.

A Cherokee Town

There is evidence that Hernando De Soto explored portions of Tennessee in 1540, and another Spaniard, Juan Pardo, crossed through about 25 years later. The Spaniards barely noticed the natives of the region, except to steal from them and kill them, but Pardo’s expedition did note the name of one of the towns through which they passed— Tanasqui . Was this the same village that the English and French would recognize centuries later as an important city of the Cherokee nation? Of course, we’ll never know, but certainly this is the first instance of this word being applied to this region. Not finding cities of gold as they had in Mexico and Peru, the Conquistadores, mercifully, did not stay long in the area, and Tennessee remained relatively untouched by Europeans for the next century.

By 1673, however, the state was virtually crawling with Europeans. Okay, not exactly crawling, but ironically, after a hundred years of isolation from whites, both ends of Tennessee saw Europeans creeping in upon its borders at virtually the same time. In the west, the French adventurers Marquette and Joliet were paddling down the Mississippi River, possibly stopping near the modern city of Memphis. The same year, maybe even on the same day, two Virginians, Gabriel Arthur and James Needham, were climbing to the top of the Great Smoky Mountains in eastern Tennessee, and peering into the lush hunting grounds of the Cherokee, Creeks, Chickasaw and Shawnee. Of these tribes the Cherokee were the most prominent in the region.

By the early 1700s the English in Virginia and both Carolinas were trading regularly with the Cherokee Indians on the other side of the Appalachian mountains. They called these natives “Overhills” and referred to the river on which they lived as the “Cherakee River,” or sometimes as the “Tennasee River,” after one of two villages situated in a sharp bend in the river.

It is believed that the other village, “Chota,” was much smaller during the first two decades of the 1700s, but that it gradually grew quite large, and eventually enveloped Tenase (there are at least twenty different spellings from early maps and journals) until the latter eventually "disappeared." Alas, any further archaeological study of the site of the village of Tenase is impossible, as it was inundated by the creation of the Tellico dam in 1979, the same dam that made the tiny, endangered snail-darter famous in the 1970s. By the middle of the eighteenth century the name “Tennessee” was in common usage among the English to describe a vague region and a river just over the mountains.

An excellent article by Bill Baker which appeared in the Tellico Times , entitled “The Origin of Our State’s Name,” describes the history and possible definition of the word. While some believe it means “big spoon,” a more likely meaning, according to Baker, is a combination of two popular theories:

that it is a derivation of a Yuchi Indian word meaning “meeting place” or that it is a Cherokee word which means “bends.” The Cherokee language, Baker says, is notoriously vague, but the suffix “ee” was commonly used to refer to a place, so if “Tennessee” meant “the bends place,” it may very well have meant a place where the river bends. And if it referred to a place in the river where it bends so sharply that it comes back upon itself, the name “meeting place” now also makes sense.

As for its spelling, Baker says that it was probably James Glen, Royal governor of South Carolina from 1738 to 1756, who gave us the modern spelling of “Tennessee,” using its current form in much of his official correspondence in the 1750s.

Watauga...and beyond

By the early 1770s several groups of colonists had traversed the Smoky Mountains and settled into hunting and farming. But it was a perilous place to live. The British government had surveyed a section of land beyond which colonists were forbidden to settle, and the Watauga River settlement, as well as two other small groups of settlers, had crossed that line. The British government simply refused to acknowledge the settlements, and though they were not made to move, they were given no governmental authority, no lawmen and no laws.

So they created their own. The Watauga Association is proudly described by Tennessee historians as the first attempt at real self-government by Europeans in the New World. They set up a five-person legislative council, and elected a sheriff, a clerk and some other officers. They made their own agreement with the local natives and governed themselves successfully for approximately three years. Lord Dunmore, governor of Virginia, raised an eyebrow, writing that this enterprising group of people set “a dangerous example to the people of America, of forming governments distinct from and independent of his majesty’s authority.”2

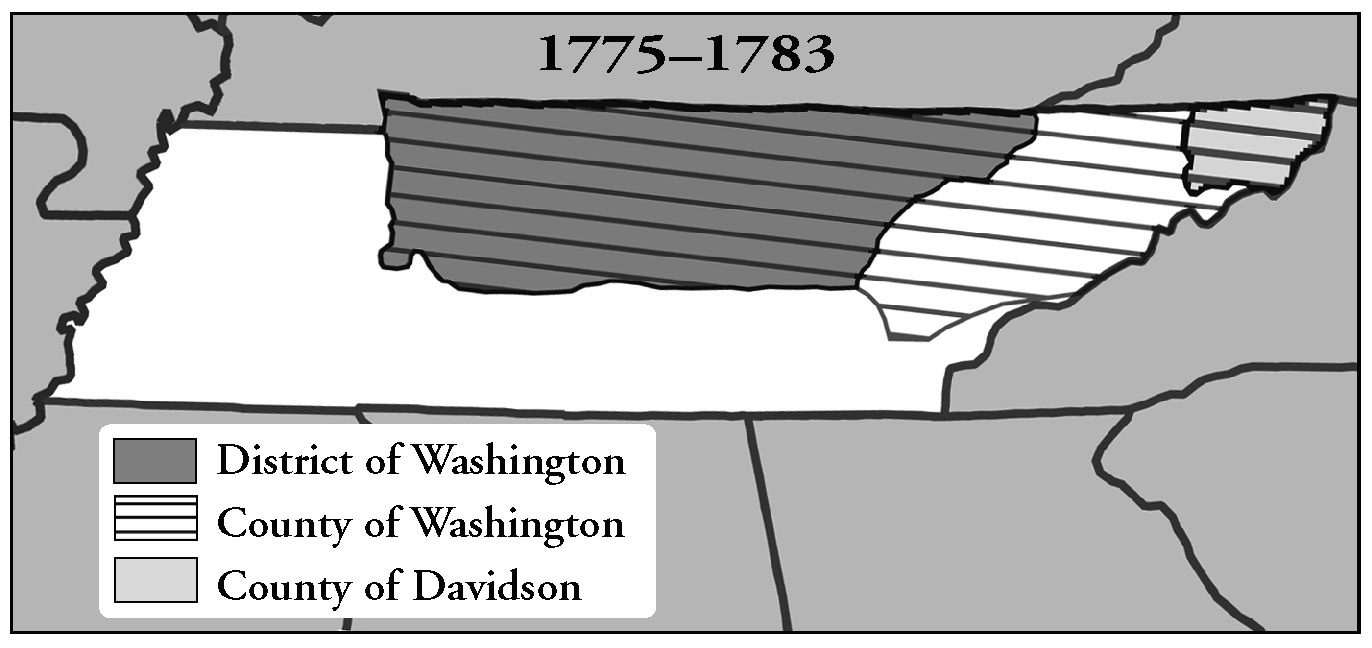

With the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, the Watauga Association changed its name and its form to the “Washington District” (yes, for George Washington) and the following year requested annexation by North Carolina. This was achieved, and the Watauga settlements now became “Washington County” in the state of North Carolina.

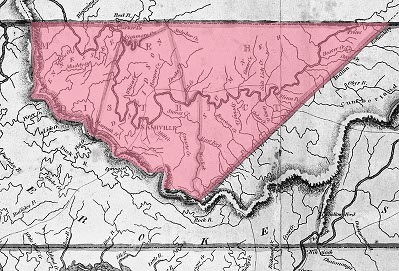

In 1779 the community of Nashborough Station was founded in Middle Tennessee, named for a Revolutionary War hero named Francis Nash. Residents of this, and a few surrounding communities, all founded by a colonizer named Richard Henderson, signed a document called the Cumberland Compact which declared themselves separate from the state of North Carolina and outlined their own government. But the Cumberland pioneers had a difficult time the first two years and were relieved when they, too, were annexed by North Carolina as Davidson County.

Name changes now came fast and furious. In 1786 Nashborough was renamed Nashville, and Davidson County was divided to create Sumner County. Two years later those two counties were further divided to create Tennessee County, and the three of them were designated the Mero District, a form of flattery toward the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Don Estevan Mero (also spelled Miro), who was threatening to bar American shipping on the Mississippi River.3

Franklin

Meanwhile, back in east Tennessee, more counties and several towns had been created to accommodate an influx of settlers. Now, safely tucked into North Carolina’s domain, these towns became stifled and restless once the Revolution ended, as they no longer needed the mother state’s protection from the British.

In 1784, before the Northwest Ordinance had been designed to dispose of western lands, the residents of what was now being commonly called “Tennessee Country” made the decision to request statehood under the leadership of John Sevier. When North Carolina ceded its transmontane lands to the federal government a constitution was adopted by the citizens of this region, Sevier was elected governor, and a name was decided upon: Franklin.

Interestingly, the preamble to Franklin’s constitution refers to the name of the new state as “Frankland.”4 This may have been a simple misspelling or a cute play on words, but the name adopted by the petitioners was indeed Franklin and was intended to honor Benjamin Franklin.

Later in 1784, however, North Carolina rescinded its cession of the lands, and Franklin once more reverted to Washington, Greene, and Sullivan Counties. Its residents were not pleased, and Sevier entered into a war of words with the North Carolina government, which at its peak threatened civil war if Franklin was not granted independence. But instead of taking up arms, the people of Franklin appealed to the new federal government for statehood. When that effort failed by a slim margin, Franklin ratified their own constitution and began to function as a separate state without sanction from either North Carolina or the federal government.

Unfortunately, Sevier proved to be a contentious leader, and there was much infighting among the elected officials of Franklin. Still, the “state of Franklin” managed to exist for four years. Eventually, poor relations with local Indian tribes coupled with the serious efforts by North Carolina to bring Franklin back into the fold proved the end of this independence movement. In 1788 the mother state pardoned all of those who had “seceded,” and Franklin quietly faded back into Washington, Sullivan and Greene counties of North Carolina...from whence it had come.

Statehood

Only a year after the Franklin movement ended, North Carolina finally (it was next to last among the thirteen colonies) ratified the U.S. Constitution. By mutual desire of the state, the feds and the transmontane residents, North Carolina once again ceded her western lands. This time for good. Now this rebellious community was an issue for the federal government, to the relief of virtually everybody.

In 1790 Congress created the “Territory of the United States, South of the River Ohio,” more commonly called the “Southwest Territory.” This name would imply a much larger region than the thin strip that is the state of Tennessee, but in fact it included only what would become that single state. What is now Kentucky was a county of Virginia and was excluded from that state’s cession agreement with the U.S. south of Tennessee were lands that were claimed by Georgia, which would not be ceded until 1802. So the Southwest Territory consisted only of the North Carolina cession.

Unlike its counterpart, the Northwest Territory, it was fairly clear that the Southwest Territory would not need to be divided. In fact, federal officials were disappointed to learn how little public land had become available when it obtained the region. But like the Northwest, the Southwest also had to bide its time and work through the process of becoming a state, waiting for Congress to establish procedures for doing so. The Northwest Ordinance had outlined the steps, but making them a reality took time.

In 1796 delegates from the Southwest Territory met in Knoxville to frame a constitution. Included in this group of delegates was the future president, Andrew Jackson, and tradition holds that it was he who suggested the name “Tennessee.” However, the name was already being used to describe the whole state, due largely to an essay called “Short Description of the Tennessee Government,” written in 1793 by Daniel Smith and republished in 1795 with an accompanying map. Smith was a long-time resident and prominent leader of the Cumberland Basin region that included Tennessee County and had been active in the region’s push for self-government, including the “Franklin” statehood movement. At any rate there appears to have been no serious debate concerning the now popular name for the region, and so Tennessee it would be.

Congress debated Tennessee’s statehood in May of 1796, working out the kinks in the process, and finally agreed to admission on May 31. President Washington signed the statehood bill the next day, and so on June 1, 1796, Tennessee became the sixteenth state to join the Union.

End Notes

1. Dykeman, Wilma, Tennessee: A Bicentennial History, (New York: WW Norton, 1975), p. 3.

2. Caldwell, Mary French, Tennessee, the Dangerous Example: Watauga to 1849, (Nashville, 1974), p. 29.

3. Bergeron, Paul H., Stephen V. Ash, Jeanette Keith, Tennesseans and their History, (Knoxville, 1999), p. 36.

4. Bergeron, et al., p. 40.