SOUTH DAKOTA

“Henceforth, with paths diverging, North and South Dakota can no more walk together. But, with honesty of purpose, exalted aims, and hallowed recollections to stimulate, they will never forget that they are still Dakota.”

—Frances Chamberlain Holley,

Once Their Home: Our Legacy From the Dahkotahs

He said, “I hope to God she finds the good-bye letter that I wrote her

But the mail don’t move so fast in Rapid City, South Dakota.”

—Kinky Friedman, Rapid City, South Dakota

Allies

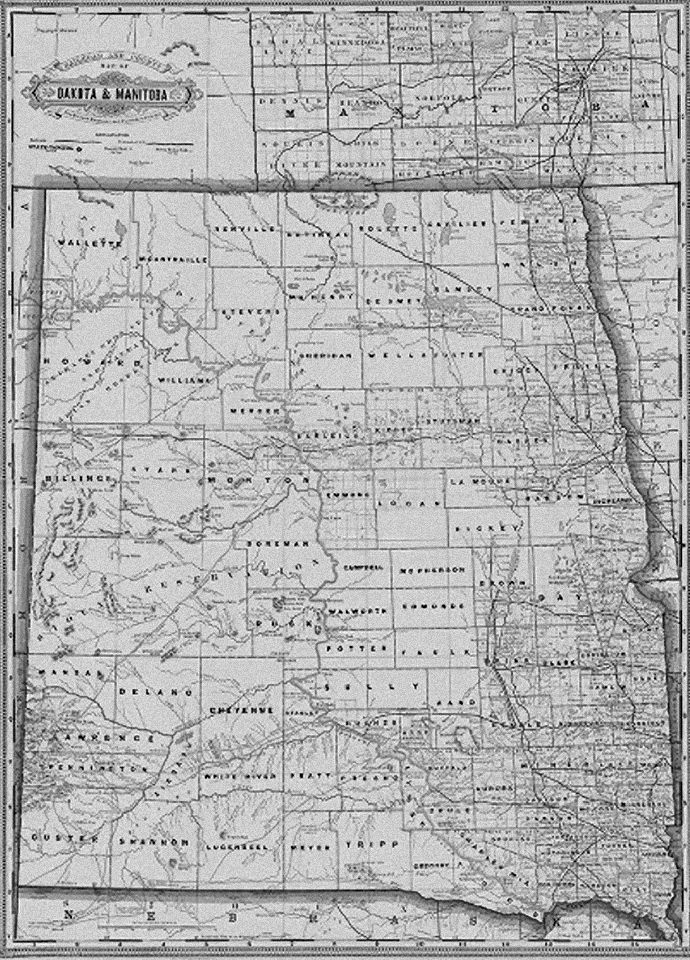

Dakota means “ally” in the language of the Dakota Indians. It is perhaps appropriate then that the name belongs to two states—states which, like siblings, share a common history. Often referred to as “sister states,” North and South Dakota were simply “the Dakota Territory” until their concurrent statehood in 1898, when they were separated upon entering the union. While they have since developed their own identities, their histories are inextricably linked, especially with regard to their names.

Unlike its sister state, however, South Dakota has cultivated an image conducive to its lucrative tourism industry. The Black Hills, Mount Rushmore, the Badlands, and the gambling town of Deadwood are all easily associated with South Dakota. Admittedly all of these tourist destinations are concentrated in the southwest corner of the state, but they are fundamental to its image and are an important reason why South Dakota has never sought to change its name, as its northern ally has contemplated.

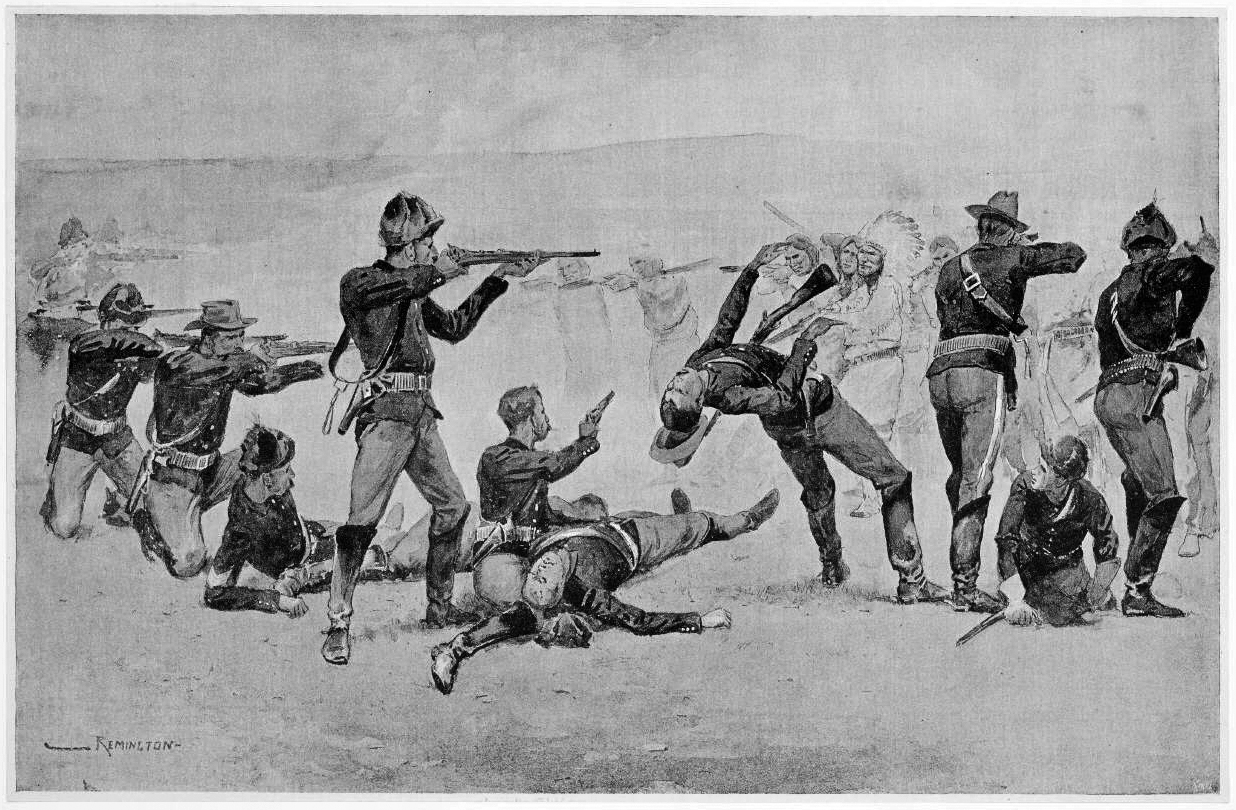

South Dakota is also strongly associated with Native Americans and their struggle with white settlers and the U.S. military in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The aforementioned Black Hills were a sacred homeland of the Sioux tribe. Besides being the site of Mount Rushmore with its all-American connections and history, the Hills are also home to the in-progress, and just as massive, sculpture of Crazy Horse, the famous Lakota warrior. Also in South Dakota is the battleground of Wounded Knee Creek, where the final armed conflict of the Lakota Sioux with U.S. troops took place. About 300 Sioux were killed in a short, confused conflict that most historians label “Wounded Knee Massacre.”

The chapter on North Dakota discusses the history of the name “Dakota” up until territorial status was applied in 1861. This chapter, then, will describe the division of the territory and the decision to share the name once statehood was imminent.

Lincoln Territory

The first agitation for separation from Dakota Territory came from the Black Hills region—that same region that is now so important to the tourism industry of South Dakota. In 1874 gold was discovered in these hills, and miners flooded the area; these miners were veterans of the gold fields of California, Nevada, Colorado and Idaho who were familiar with how to establish a mining-town government. In 1877 a convention was held in Deadwood where delegates to Congress were elected and a name for their new territory was selected: Lincoln.

Proponents of this division eventually selected Sheridan City to be the capital of the new territory and managed to gain support in Congress, but not enough. Though the movement continued for years, no bill ever passed in Congress, and the “Territory of Lincoln” never materialized.1 Still, the miners in the Black Hills and the citizens of the towns that supplied them, namely Yankton and Vermillion in the southeast (Yankton was the Dakota territorial capital), felt increasingly distant from the rest of the territory, and continued lobbying for separation and immediate statehood.

North vs. South

As for the north, its settlers had their own motivations for wanting separation but not until after 1873. Before that year the economic ties of the very sparsely populated north—whose settlements consisted of Pembina and the Red River valley region—extended east to St. Paul and north to Canada. But in 1871 the Northern Pacific railroad was granted an enormous swath of land to build a track from St. Paul all the way to the west coast. By 1874 the track extended to the “end of track” town of Bismarck on the Missouri River, but the bottom had dropped out of the U.S. economy, and the Northern Pacific Railroad needed to find ways to make a return on its investment without laying any more track.2

The extreme overbuilding of railroads, especially those of the Northern Pacific, are largely to blame for the Panic of 1873, a depression which began with the failure of a prominent Philadelphia bank, followed by the collapse of the Vienna stock exchange. The economic turmoil affected not only the U.S. economy, but that of Europe as well. The depression lasted five years, during which time the railroad company moved furiously to import farmers to the northern region of the Dakota Territory as a way of providing a transportation market for itself.

One farmer whose assistance the railroad companies sought was Oliver Dalrymple, a Minnesota attorney who had gained a reputation as a very successful wheat farmer. That success had earned him the nickname “King of Wheat,” and when approached by General George Cass, president of the Northern Pacific Railroad, to help draw farmers into northern Dakota, Dalrymple obligingly moved there from Minnesota. The influx of “bonanza farmers” who heard of Dalrymple’s success helped achieve the goal of the Northern Pacific and made Bismarck the undisputed center of the agricultural industry in the northern section of the territory.

Wheat farmers and railroad agents in the north, miners in the south. This was the way the regional affiliations broke down, and as the mining industry began to feel the powerful influence of the railroads, they complained (somewhat justifiably) of political persecution by outside interests. For in 1878, every railroad in Dakota was owned by an out-of-territory company.3

Capitals

In 1879 delegates from the north officially, though unsuccessfully, requested that the territorial capital be moved fromYankton toBismarck. This was a touchy subject for the powerful political forces in Yankton, and one which they had dealt with before. In 1862George M. Pinney, Speaker of the first Assembly, resigned his speakership when he learned that the opposition intended to throw him through a closed window for his failure to support Yankton as the capital.

Later, in 1883, the powerful Bismarck forces pushed a bill through the legislature to create a capital removal commission, whose job would be to scope out possible new sites for a capital. The commission was to meet in Yankton within thirty days of its creation or lose its mandate. But the commission had some rather creative opposing forces, as historian Howard Roberts Lamar explains:

“...the Yankton citizens still had hopes of halting the entire scheme by preventing the commission from meeting within the city limits. The three members of the Yankton commission were carefully watched; any suspicious gathering was reported, and the local members of the commission were openly threatened with violence.”

After some time, the Yanktonians thought they had succeeded in stopping the removal of the capital. But unbeknownst to them, a slow-moving train had rolled through the city early one morning containing the members of the commission, allowing them to officially organize and assume their duties.4

The capital issue was finally resolved in favor of Bismarck in 1887, but only through the machinations of a corrupt territorial governor named Nehemiah G. Ordway. Ordway was indicted by a grand jury for irregularities—including bribery in the process of moving the capital—and removed as governor in 1884. Still, his influence continued, and in 1887, the funds were released to move the capital to Bismarck. Ordway, who owned much property in Dakota Territory, would continue even after his removal as governor to lobby Congress against statehood for Dakota, and against division.

The attempts to move the capital were the most obvious signs of irreconcilable differences between north and south. It was now clear that division was not only inevitable, but desired by both sides. But it wasn’t divorce. It was more like two sisters marrying into different families.

Division

In 1885 the strong statehood forces in southern Dakota grew tired of lobbying Congress for admission and took matters into their own hands. They organized a convention atHuron and drew up a ballot for a popular election to be held south of the forty-sixth parallel. In November of that year the citizens of southern Dakota declared themselves to be the “State of Dakota,” and they elected a governor, adopted a constitution, and selected Huron as their capital.

The northern Dakotans immediately objected to the choice of names chosen by the southerners, claiming that the name “Dakota” had been made famous by its own brand of wheat. At any rate, the U.S. Congress was unimpressed, and continued to refuse admission, favoring a one-state plan (on the advice of Ordway, among others).

In November of 1887, a popular election was held within the territory on the question of division. To the surprise and dismay of division and statehood advocates, the north opposed division by a huge margin, and the south favored it only slightly. Blame was immediately placed on the influence of the railroads, even accusing the Northern Pacific of “fixing” the election.

Divisionist leaders mobilized quickly, exposing to Congress and to Dakotans the corrupt motives of the railroad companies and one-state advocates. Most of the nefarious reasons against separation and statehood had to do with land speculation and keeping control of government offices through bribery and graft. These reasons would play out in many territories where the government officials were appointed, and therefore easier to control through corruption. Once statehood was granted the officials of the state would be elected, and would be much more difficult for law-ignoring land-speculators to control.

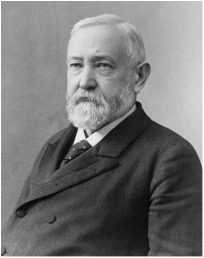

To try a new tack, southern Dakotans proposed a new idea. Instead of lobbying for statehood only for themselves, they began to advocate immediate statehood for both halves of Dakota. While all of this activity was helpful in garnering support for their cause, the statehood proponents truly won their fight when Indiana Senator Benjamin Harrison, a long-time supporter of Dakota statehood (and division), won election to the U.S. Presidency.

Seeing the handwriting on the wall, a now lame-duck Congress beat Harrison and his supporters to the punch. On February 22, 1889, Congress passed admission bills for North and South Dakota.

Still Sisters

The concept of sister-statehood was one that President Benjamin Harrison took seriously. On November 2, 1889, when the proclamations for statehood were prepared for him to sign, Harrison felt the need to avoid the appearance of favoritism by allowing neither state to claim that it had been chosen to enter the union first. Therefore his Secretary of State, before presenting him with the statehood documents to sign, covered the text and shuffled the papers. Once the President’s signature was applied, the papers were again shuffled—this time by a different person.

The effort had the desired effect. No one knows which state entered the union first—which was 39th and which was 40th. However, by virtue of its name North Dakota, the undisputed alphabetical leader of the two, generally appears before South Dakota in lists where such detail matters.

End Notes

1. Lamar, Howard Roberts, Dakota Territory 1861-1889, (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1956), p. 165.

2. Lamar, p. 191.

3. Lamar, p. 192.

4. Lamar, pp. 204-205.