RHODE ISLAND

AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS

“She came from Providence, the one in Rhode Island…”

—The Eagles, The Last Resort

“Brian: We’re quite a pair of partners,

Just Like Thelma and Louise.

‘cept you’re not six feet tall

Stewie: Yes and your breasts don’t reach your knees.

Brian: Give it time.

We’re off on the road to Rhode Island.

We’re certainly going in style.”

—TV Show “The Family Guy”

We’re Off on the Road to Rhode Island

It’s Small

The smallest of all of the United States has the biggest name. Officially, it is “Rhode Island and Providence Plantations”—that’s approximately one letter for every 38 square miles, compared to 126,000 square miles per letter forAlaska.

It is a state famous for its smallness, indeed proud of its smallness—or should we say smallestness ? In fact while it boasts many superlatives—first to declare independence from England, last to ratify the Constitution, first to ban the importation of slaves—it is fair to say that being the state with the least land mass distinguishes Rhode Island more than any other feature or achievement. Rhode Island contains only five counties. It has half the land mass of the second smallest state (Delaware) and only a little more than the city of Los Angeles. It is about the size of Utah’s Great Salt Lake, its longest section of interstate (I-95) runs only thirty miles, and it would get lost inside Yellowstone National Park. One of the state’s nicknames is, in fact, “Little Rhody.”

Of course, for such a small state Rhode Island has plenty to distinguish it. There is the harbor town of Newport, one-time frolicking ground of the dynastically wealthy. Around the turn of the twentieth century, no matter how much wealth you had amassed, if you weren’t seen around Newport, R.I., hobnobbing with the likes of Lady Ascot and the Vanderbilt family in their majestic estates and tony mansions, you simply hadn’t made it. Some may think of yacht-racing, the sounds of halyards clanging in a marina, of sailboats easily coasting along its shores.

But Rhode Island is remarkable for an even more noble reason. Its founder, the intrepid writer and self-made scholar Roger Williams worked tirelessly to make the colony a place of true religious freedom, a quality he found sorely lacking in Massachusetts in the 1630s. (More on Mr. Williams later.)

But no matter your image, when it comes to Rhode Island, the overwhelming feature is that of being, at least where size is concerned, decidedly non-overwhelming.

Divinely Ordained?

Humorist Dave Barry once wrote that he thought that states’ names were “decreed by the Bible or something” or that they were “actually, physically, written on the continent, in gigantic letters, the way they are on maps.” If that’s the case then someone might want to keep handy their giant bottle of white-out for Rhode Island. In 2010 a measure was placed on the state ballot to change its name from “Rhode Island and Providence Plantations” to simply “Rhode Island.” Backers of the amendment claimed that the word “plantation” was too closely associated with slavery, and therefore offensive to African Americans. Those opposed pointed out that in the 1630’s when the name was being applied, the word simply meant “community” or “settlement” and was never intended to be synonymous with the cotton plantations of the antebellum south on which black people were brutally forced into servitude.

The proposal failed, but the very attempt at changing the name of one of our fifty states runs counter to Dave Barry’s theory of divinely inspired appellations. In fact, Rhode Island isn’t the only state to consider altering the map that has been firmly cemented since Hawaii was admitted to the Union on August 21, 1959. North Dakota has twice—once in 1947, and again in 1989—defeated attempts by some of its legislators to remove the word “North” from its name, fearing that it hinders tourism in the state because, as Mr. Barry explains, the word “connotes a certain northness.”

For most of us, the names of our states have not changed in our lifetimes, and if Rhode Island and Providence Plantations is any indication, it seems that that giant bottle of white out won’t be necessary after all.

Rhode Island...

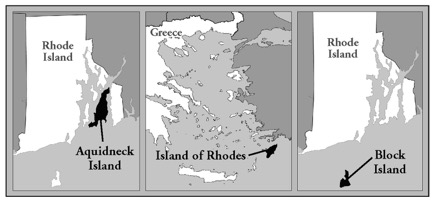

Rhode Island is, in fact, an island. (The state, however—as will be discussed more in depth later—is made up of both the island and the surrounding mainland.) Situated snugly in Narragansett Bay, the natives, Narragansett Indians, called it “Aquidneck” which simply meant “at the island” or “at the floating mass.” This Narragansett name was actually used by the earliest Rhode Island settlers and never completely faded from usage. In fact, today the island is commonly referred to as “Aquidneck,” leaving “Rhode Island” free to describe the entire state.

One of the two dominant theories about how Rhode Island came to be named holds that the Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazano who navigated the bay in 1524, named it for its similarity in size and shape to the Greek island Rodhos or “Rhodes.” The Greek island, in turn, has two competing theories about the origin of its name. The first is that it was named for a Greek nymph called Rhodes, who was the wife of the island’s patron God, Helios—the sun god. The other theory is that its name derives from the ancient Greek word for rose and describes the abundance of flowers on the island. Home of one of the seven ancient wonders of the world, the Colossus (now there’s a word one does not immediately associate with smallness)—a massive bronze statue of Helios that was destroyed by an earthquake in 226 BC—Rhodes does indeed bear similarities in shape to Aquidneck.

A variation on the Verrazano theory is that it was Roger Williams, the undisputed founder of Rhode Island, who actually applied the name “isle of roses” to Aquidneck, referring to it being “bedecked by rhododendrons.”1 In another digression lies the theory that Verrazano, on his 1524 voyage, was actually describing Block Island, but that Williams and his colleagues confused it with Aquidneck, and applied the name erroneously. This theory springs from the writings of Verrazano himself: “...an island in the form of a triangle, distant from the mainland ten leagues, about the bigness of the Island of Rhodes.”2 Verrazano named this island “Luisa,” after the mother of his benefactor, King Francis I of France. Block island is the correct distance from the mainland to fit this description, and is in fact shaped like a triangle. Aquidneck, on the other hand, lies within the bay itself, nearly touching the mainland.

founder of Rhode Island

While it is impossible to know—five centuries later—to which island Verrazano was referring, the most likely conclusion (and the most popular theory today) is that it was Block Island that he named Luisa, and that any similarity of Aquidneck to Rhodes is coincidental.

Ninety years after Verrazano, Narragansett Bay was explored by a Dutch navigator named Adriaen Block. He is not only the namesake of Block Island, but the source of the second dominant theory about the origin of the name Rhode Island. In this version, after sailing around the largest island in the Bay in 1614, sometime after he had founded and named Block Island for himself, Block recorded the name of his discovery as “Roodt Eylandt” (Red Island), due to the “fiery aspect of the place, caused by the red clay in some portions of its shores.”3 Those who espouse this theory believe that the anglicizing of “Roodt Eylandt” is a much easier leap than the dropping of the “s” from “Rhodes.”

...And Providence Plantations

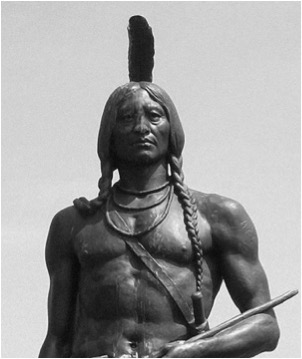

The origin of “Providence Plantations” is not nearly so obscure as that of the name “Rhode Island.” It was bestowed by Roger Williams, the aforementioned founder of the colony, in 1636 after his banishment from Massachusetts Bay Colony for having

“...broached and divulged divers [sic] new and dangerous opinions, against the authority of magistrates...and yet maintaineth the same without any retraction4.”

Williams was a true pioneer in the concept of separation of church and state. His “divers [sic] new and dangerous opinions” were basically threefold:

-

that the King had no right to give away lands in the New World that belonged not to him but to the Indians,

-

that the magistrates should not have authority over the religious beliefs that a man held, and

-

that “whole nations and generations of men have been forced...to pretend and assume the name of Jesus Christ which only belongs...to truly regenerate and repenting souls.”5

While his tolerance for other religions was not necessarily greater than that of some of his contemporaries, his firm belief that religious law should not govern civil matters was absolutely novel and pure heresy at the time.

Williams was encouraged by John Winthrop and John Winslow, governors of Massachusetts Bay Colony and Plymouth respectively, to go to Narragansett Bay after he was banished from their colonies. They knew that the bay was just beyond the borders of the Plymouth colony, from which Williams was exiled, and that it was south of the MBC charter, so that no English claim existed to that land. They also knew, as did Williams himself, that it was the home of Massasoit and Canonicus, sachems of the Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes, with whom Williams had become friends.

While Roger Williams took the advice of his friends and settled in the Narragasett Bay area, he was not the first Englishman to do so. William Blackstone, another escaper of religious persecution, had settled there about a year before Williams moved in. He built a home near a river (now called Blackstone River) and called it “Study Hill” where he read prolifically and ministered to the Indians. But Blackstone “cannot be considered a real founder of the State. He gathered no band of colonists about him....”6 Clearly, Blackstone’s preference for reclusiveness kept him from vying for the title of Founder.

Artist: Edwin Austin Abbey

Williams, on the other hand, gratefully purchased property from the Narragansetts for the specified purpose of founding a plantation (village) for himself and his followers. Once banished from the MBC in 1635, Williams was allowed to remain at Salem, where he was living with his family, on the condition that he not preach his heresy to other church members. He found this impossible, however, and was sentenced to be deported to England, but instead he fled south to Narragansett Bay. He was joined by a small group of followers the next spring, and they settled along the Seekonk River. Informed by Winslow that they were still within the bounds of Plymouth Colony, they removed—with the help of the Narragansetts—to an area on the mainland at the mouth of two rivers, the Moshassuck and the Woonasquatucket at the northern tip of the bay. He named the place Providence

“from the freedom and vacancy of the place and many other providences of the most holy and only wise.”7

Forming a State

In April of 1638, John Clarke and William Coddington, two former MBC residents, established the town of Pocasset at the north end of Aquidneck. The town was later renamed Portsmouth and into it moved Anne Hutchinson, another exile from MBC, who, like Williams, had been banished for her heretical teachings. Coddington, in a disagreement with Hutchinson, left in May of 1639 to found the community of Newport at the opposite end of the island. Eventually the towns united under one governorship, and in March of 1644, the general Court of Election ordered that “the ysland commonly called Aquethneck, shall be from henceforth called the Isle of Rhodes, or RHODE ISLAND.”8

The phrase “Aquednetick, called by us Rode-Island” appears in a letter from Roger Williams to John Winthrop in May 1637(9), but no clarification is given as to why they renamed it. In fact, in many subsequent letters from Williams, he uses the aboriginal name of the island, but it is also the case that much of Williams’ correspondence is lost to us. Regardless, it is clear that the name “Rhode Island” was in at least limited use by its English residents very shortly after they arrived.

At the time the court handed down the decree to change the name of their colony, Roger Williams was in England securing a patent for Portsmouth, Newport, and Providence Plantations. He returned in September of 1644, with the patent he received from the Earl of Warwick, titled “The Incorporation of Providence Plantations, in the Narragansett Bay, in New England.” It makes no mention of any island, neither Aquidneck nor Rhode. However, by the time Williams requested and received royal confirmation of this patent in 1663, the name Rhode Island seems to have been settled upon to apply to the entirety of the area, including Providence on the mainland, and the island of Aquidneck/Rhode. In July of that year King Charles II granted a charter for “Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.”

Revolutionary Rhode Island

On May 4, 1776, a full two months before the Declaration of Independence was drafted and signed, Rhode Island became the first of the colonies to declare itself independent from the British royal and parliamentary rule. Shortly after the rest of the fledgling country followed suit, Rhode Island codified its official name when, on July 18, 1776, the General Assembly at Newport resolved that

“the style and title of this government...shall be the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.”10

As for the boundaries of the state, one state history points out that for such a small area—1084 square miles—the boundaries took an agonizingly long time to settle. The book quotes Rufus Choate, a Massachusetts politician, who declared that Rhode Island’s borders

“might as well have been marked on the north by a bramblebush, on the south by a bluejay, on the west by a hive of bees in swarming time, and on the east by five hundred foxes with firebrands tied to their tails.”11

The final establishment of the border with Connecticut was settled by King George in 1728, but the border with Massachusetts proved more difficult to determine. The dispute eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court and wasn’t firmly settled until 1887.

Once the American Revolution was won, Rhode Island was the last (13th) of the colonies to ratify the Constitution. It finally did so on May 29, 1790, after receiving assurances that the Bill of Rights would be adopted as law.

End Notes

1. “Rhode Island State History,” http://www.negenealogy.com/ri/ri_history.htm, accessed 7/25/09.

2. Wroth, Lawrence C., The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano1524-1528 , (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1970), p. 137.

3. Arnold, Samuel Greene, History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations , (D. Appleton and Co., New York, 1859), p. 17.

4. Easton, Emily, Roger Williams: Prophet and Pioneer , (AMS Press, New York, 1969), pp. 168-169.

5. Easton, p. 164.

6. Rhode Island: A Guide to the Smallest State (Writers program, Rhode Island, 1937), p. 32.

7. Easton, p. 179.

8. Rhode Island: A Guide to the Smallest State, p. 44.

9. LaFantasie, Glenn W., The Correspondence of Roger Williams , (Brown University Press, 1988), p. 73.

10. LaFantasie, p. 44.

11. LaFantasie, p. 36.