PENNSYLVANIA

“…From the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania, let freedom ring…”

—Martin Luther King, Jr.

Numbers I’ve got by the dozen

Everyone’s uncle and cousin

But I can’t live without buzzin’

Pennsylvania Six, Five Thousand

—Glenn Miller, Pennsylvania 6-5000

And we’re waiting here in Allentown

For the Pennsylvania we never found

—Billy Joel, Allentown

Father and Son

One need not be a history buff to know the derivation of the name Pennsylvania . While Americans have a famously diminished knowledge of their own national history, most could probably tell you that Pennsylvania is named for William Penn. Many could even tell you who William Penn was. But what many Americans may not know is that, technically speaking, Pennsylvania was actually named not for William Penn, famous founder of the colony and preserver of religious freedoms, but for his father, William Penn... Senior .

Here’s something funny…Think about Pennsylvania State University. I know, I know, nobody calls it Pennsylvania State University, and anyway, why would the mere mention of the Keystone State’s flagship university set you to guffawing? It’s only funny in that American history, name nerd kind of way. But when people speak of that particular institution, they call it Penn State— Penn being short for Pennsylvania. But in actuality, the word Penn isn’t short for anything. It is the word Pennsylvania that was newly created—out of the name Penn . So when one says “Penn State” one is shortening a word that was lengthened to create the state name (actually the colony name) in the first place.

Of course, when we hear the word Pennsylvania we also think of the Amish with their plain, buttonless clothing and horse-drawn carriages, of the smokestacks and steel factories in Pittsburgh, and of the Americana and history scattered throughout Philadelphia. Movies like Witness , The Deer Hunter , and National Treasure are filled with these Pennsylvania icons.

But perhaps the most socially relevant film to feature this somewhat conservative, working-class state was 1993’s Philadelphia with Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington. Philadelphia was one of the first major motion picture to portray a gay man dying of AIDS, not as a homosexual stereotype, but rather, realistically and sympathetically, allowing the City of Brotherly Love to lead the way in de-stigmatizing this important social health issue.

The Experiment

Pennsylvania, as already mentioned, calls to mind Quakers or Amish, with their horse-drawn carriages and simple, black clothing that hasn’t changed in roughly three-hundred years. This image is, of course, appropriate because the colony was originally founded to accommodate this particular group of settlers from Europe. Religious tolerance and equality among all men were the cornerstones of the “experiment” that William Penn and his friends wished to implement—to see if a society could live without hierarchies in politics, society, or religion; to see if people really could consider others their equal in all aspects of life. Pennsylvania, the experiment, was of course wildly successful, its beliefs and values spilling over into the other colonies. Here was an example, if perhaps a bit extreme, for the American Revolutionaries to show the world what they were fighting for. Here was a lifestyle available nowhere else on Earth, and even though some Quakers were among the first “conscientious objectors,” refusing to fight in any war, their new freedoms were, to others, worth fighting to save, possibly even worth making the ultimate sacrifice.

Of course, for other reasons too, Pennsylvania reminds us of those revolutionary days, the heady times of Benedict Arnold, Benjamin Rush, and Betsy Ross. We think of Independence Hall, and of the Liberty Bell. We think of Benjamin Franklin strolling the streets of Philadelphia, his own newspaper, the Pennsylvania Chronicle, tucked under his arm.

Moving ahead chronologically, Pennsylvania gave us early coal-mining and steel production. And still further along we get Penn State, the Nittany Lions, and Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant in the incomparable Philadelphia Story.

If the name “Pennsylvania” brings to mind a single theme, that theme must be “Americana.”

A Brief Summary

William Penn, the younger, grew up during a time of severe religious persecution that had its roots in King Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church and creation of the Church of England in 1534. Some saw the dispute with Rome as an opportunity to “purify” their religion—to abolish the sacraments and abandon the traditions and ceremony of the Roman Catholic Church and reform Christianity into a religion based solely on scripture. The Puritan movement spread throughout Europe and produced several extremist sects, most notably the Pilgrims and, later, the Quakers.

Henry’s daughter, Queen Mary—”Bloody Mary” to her detractors—restored Catholicism and executed protestant ministers. Her reign was brutal but mercifully short, lasting only from 1553-1558, during which time many Reformation leaders fled into hiding in Europe. They returned when Henry VIII’s younger daughter, Elizabeth I, ascended the throne and reverted the country back to the National Church of England. Queen Elizabeth I practiced somewhat more restraint with respect to the Catholics than her half-sister had shown with Protestants, opting for some tolerance of religious diversity. Elizabeth I lived a long time, long enough to see the Church of England grow and become deeply entrenched. It was during her reign that the Puritan movement became popular and widespread.

Her successor, King James VI of Scotland and I of England, was less tolerant of Catholics but also succeeded in alienating Protestants by refusing to recognize the importance of a largely Puritan parliament. His major contribution to the religious landscape was the commissioning, at the request of the Puritans, of the King James Version of the Bible. He passed down his theories, and in fact his treatise ( Basilicon Doron , 1598) on the Divine Right of Kings, to his son Charles I, who took the throne in 1625.

By this time the political situation in England was fractious and volatile. Even if Charles I had proved a capable and diplomatic leader, the task of unifying the disparate religious sides and governing his subjects would have been difficult. Charles I, however, was proud and obstinate and eventually thrust the country into Civil War, primarily over his disagreement with Parliament over whose authority—his or theirs—was supreme. Charles I was beheaded in 1649 by Cromwell and the Parliamentarians, and his son Charles II lived in exile until 1659. During that time, England was governed by Oliver Cromwell and his chosen members of Parliament. Cromwell, a Puritan, proved schizophrenic in his religious tolerance, allowing Jews and non-Anglican Protestants freedom of conscience but harshly persecuting Irish Catholics.

It was into this climate that William Penn, Jr. was born in 1644, and the religious turmoil in England would only grow and diversify further. As Penn emerged into adulthood, he enraged his father by rejecting his birthright of privilege and society and adopted the faith of the Quakers.

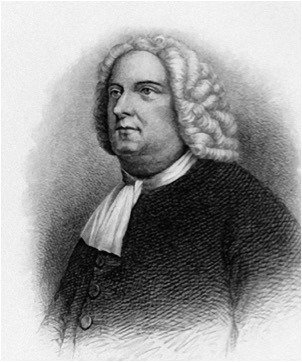

Sir William Penn, Sr.

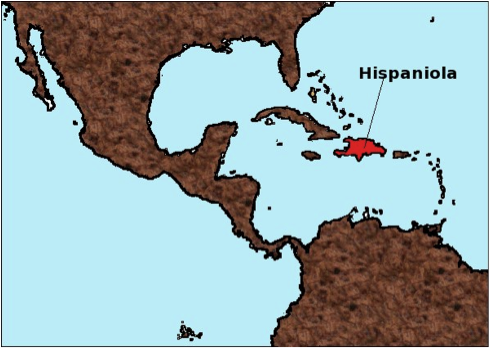

Though he was a monarchist at heart, William Penn, the elder, was also a pragmatist. He fought for the Parliamentary forces during the English Civil Wars of the 1640s and later for Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth of England against international foes. In 1655 following a severely botched offensive on Hispaniola, Penn was arrested and remanded to the Tower of London. It has been speculated that Penn was involved in intentionally losing the battle or that he made some effort to offer his ships to the exiled King Charles II, but more likely the blundered battle was simply that. Though he was released after questioning before the Council of State and after offering a full apology, he no longer sailed for the Commonwealth but retired to Ireland with his family, including his oldest son William Jr.

William Penn’s father

When Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector, died in 1658, the Commonwealth lost its most forceful and influential leader, and the Parliamentary government weakened. William Penn, Sr. was elected to a seat in the House of Commons, and within two years, King Charles II returned to London from exile to take his place on the throne of England, a throne which had been vacant for over a decade. It is clear that Penn had been loyal to his King during the exile, for he went to Holland with a fleet of thirty-one ships to bring Charles home. Before the ships returned to England—in fact shortly after boarding the vessel which would carry him—Charles II knighted William Penn.

The Quaker Movement

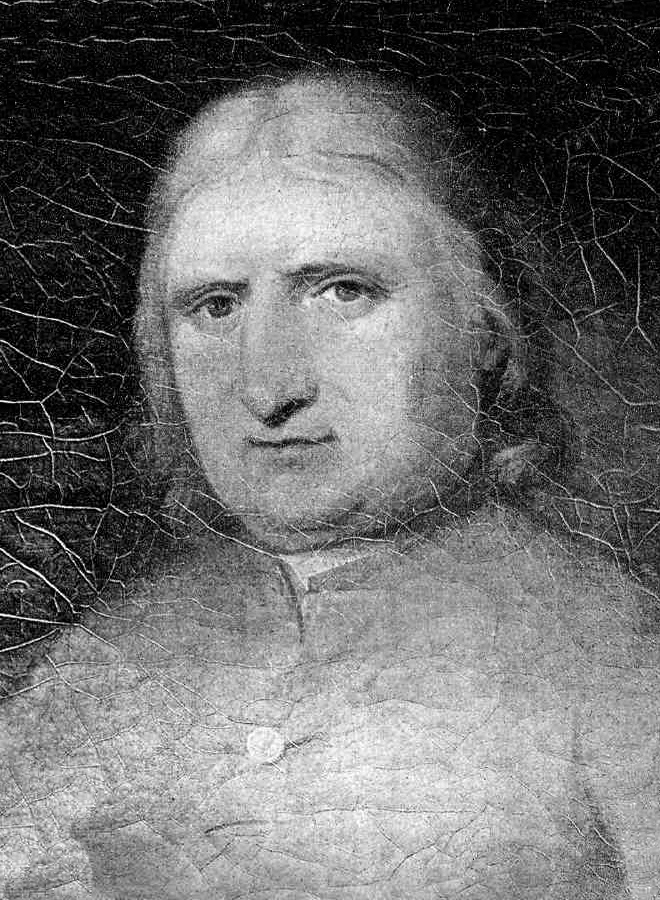

William Penn, the son, was a serious, often brooding child. He was educated at Oxford, as was customary for the sons of courtiers. During his adolescence, he was touched by the preaching of Thomas Loe, a follower of George Fox, founder of the Quaker movement.

founder of the Quaker movement

Fox, the lowly son of a weaver, was extremely intelligent and eloquent. In 1647 he experienced a personal revelation and began to preach non-violence and equality among men, a truly revolutionary philosophy during those times of forced religious subjugation and serious attention to rank and class. The Quaker label was applied to Fox and his followers even before their official name, “The Society of Friends,” was settled upon. In 1650, Fox told a justice of the peace to “tremble at the word of the Lord”, who in turn sarcastically called him a "Quaker" and imprisoned him for his preachings. The label stuck and survived its derisive beginnings when the Friends began using it to refer to themselves.

Ironically it was Penn’s father, Sir William, who had invited Thomas Loe into his home at Macroom, Ireland, to speak to a small gathering. Both father and son were moved to tears by Loe’s preaching1, but the younger William Penn would go on to adopt the preachings of Loe and Fox and become their most famous benefactor. Penn’s father, Sir William, like many in England, was as confounded by the Quakers as he was angry with them. Their absolute refusal to acknowledge a system of rank, whether that of royalty, secular authority, or even within their own community, was simply foreign−and therefore threatening−to the establishment.

In another ironic twist, it was Penn Jr.’s lofty position in that establishment which allowed him to become something of a liaison between the King’s authorities and the Quakers. He successfully secured the release of Friends who had been imprisoned for their beliefs in England and in Ireland. The younger Penn was also able (albeit with more difficulty and with his father’s help) to keep himself out of any extended stay in prison, though after his father’s death he did spend six months in Newgate, a revolting prison of the times.

Though Penn’s father sharply disagreed with his son’s radical beliefs he was apparently resigned to them by the time of his death in 1670. Penn, Jr., inherited his father’s estates (not because of any reconciliation, but due to the laws of primogeniture), and many of his other possessions including a cherished gold medal that had been bestowed upon him by Oliver Cromwell for his service in the Parliamentarian Navy.2

The Colony

For the next decade, William Penn promoted the teachings of George Fox often in Fox’s company, as well as with other leaders of the movement. He traveled throughout Holland and Germany, acquiring converts and debating his antagonists. He wrote prolifically, usually in response to attacks on the Quakers.

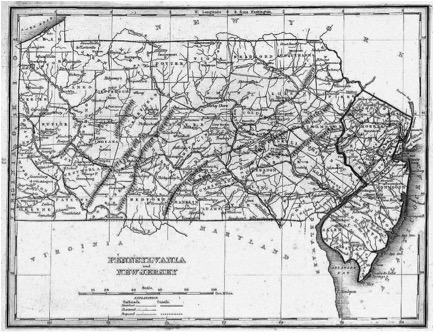

During these years, Penn and his colleagues dreamed of starting a new country, a new society, where freedom of conscience would be the foundation. It would be interesting, they believed, to see if men could live happily and peacefully in such a society, and in 1675 William Penn found himself on the verge of an opportunity to create just such a place. He was asked to arbitrate a land dispute in North America between two members of the Society of Friends who had come into some land in the province of New Jersey. The result of the arbitration granted several Quaker leaders, Penn among them, a portion of the province, and they set about creating the frame of government under which those lands would be occupied. They stipulated not only religious freedom, but elected officials, jury trials, and an end to imprisonment for debt. When the first group of colonists to test this social experiment arrived in the New World in 1677, they settled the town of Burlington on the Delaware River, a town that succeeded and prospered and eventually encompassed all of West New Jersey.

Because of this success, and because of growing intolerance of Friends in England, Penn requested from King Charles II a much larger grant of land in New England in 1681. His specifications were not for the prime coastal territories which were already increasingly populated, but for the wilderness west of New Jersey. He needed space, space for as many adventurers as wanted to participate in the social experiment like that of West New Jersey.

Land grants like these were political plums, however, and Penn, though his family had been friendly with the Stuarts, was not exactly high on the list to be granted Royal favors. But Charles II was politically savvy. He wanted to rid himself of the political opposition that the Quakers presented, but he knew his own party would resent the granting of a North American colony to a leading Quaker. Penn and Charles II came up with a resolution that was nothing short of ingenious. Instead of “granting” the territory to William Penn, the king would offer it to him as payment for a debt which the monarch had incurred from Penn’s father, Sir William. The actual debt was of the sort that were rarely repaid by kings, but its existence was serendipitous to both parties, allowing Penn his dream of a new country, and allowing the King to send shiploads of Whigs to America where they could not effectively oppose him.

The final charter for William Penn’s American colony was presented on March 4, 1681. It included confusing language about the boundaries of the colony which would cause a disagreement between Penn and Lord Baltimore of Maryland for the rest of their lives, and even between their heirs, but it named William Penn absolute proprietor of the country, beholden only to the king. As for the name of the colony, William Penn explains in a letter to an old friend, Robert Turner:

“...this day my country was confirmed to me by the name of Pennsylvania ; a name the King would give it in honor of my father. I chose New Wales , being, as this, a pretty hilly country, but Penn being Welsh for a head, as Penmanmoire in Wales, and Penrith in Cumberland, and Penn in Buckinghamshire, the highest land in England, called this Pennsylvania, which is the high or head woodlands; for I proposed, when the Secretary, a Welshman, refused to have it called New Wales, Sylvania, and they added Penn to it; and though I much opposed it, and went to the King to have it struck out and altered, he said it was past, and would take it upon him; nor could twenty guineas move the under secretary to vary the name; for I feared lest it should be looked on as vanity in me, and not as a respect in the King, as it truly was, to my father, whom he often mentions with praise.”3

William Penn made only two trips and spent a total of less than five years in his “new country,” but his influence over it was profound. He insisted upon paying the natives before inhabiting any land, and he included them in his policy of self-government. They were allowed to settle grievances in court with a jury that included settlers and natives. It is generally accepted that William Penn’s humane dealings with the natives of Pennsylvania allowed the colony’s settlers to live peacefully among them for decades.

William Penn died July 30, 1718. His later years were unfortunately plagued by illness and financial troubles, but his legacy in the United States is almost unblemished. Thomas Jefferson called William Penn “the greatest law-giver the world has ever produced.” Pennsylvania ratified the U.S. Constitution on December 12, 1787, becoming the second state in the Union after Delaware.

End Notes

1. Peare, Catherine Owens, William Penn: A Biography (Philadelphia, 1957), p. 23.

2. Peare, p. 126.

3. Peare, p. 215.