OREGON

I met him on the cliffs

of Twin Rocks, Oregon…

—Shawn Mullins, Twin Rocks, Oregon

Well Portland Oregon and sloe gin fizz

If that ain’t love then tell me what is

Well I lost my heart it didn’t take no time

But that ain’t all I lost my mind in Oregon

—Loretta Lynn, Portland, Oregon

The “New” Oregon Trail

Young children, upon hearing the word “Oregon,” may think of that piano-like instrument in the church balcony. But to the rest of us Oregon is that Pacific Northwest state full of people who have a serious bias against Californians, even though much of the state is populated with...displaced Californians. If any state has a “slam the door behind you” policy, it is Oregon—at least with regard to its southern neighbor. The flood of immigrants and refugees northward from the increasingly over-populated cities of California traveled what has been called the “New Oregon Trail” and is famously resented by those who thought to do it first.

But Oregon, to most of us, calls to mind the state’s plethora of natural resources rather than the people who move in to exploit them. Oregon’s geography is perhaps more varied than any other state. While known for its rainfall, there is also a place in western Oregon called the “Great Sandy Desert,” part of the Great Basin of the American West.

With such diverse geography it is not surprising that Oregon is famous for its natural resources: abundant timber, hundreds of varieties of fish, minerals and gems, and even rich farmland. There are also those resources we think of in terms of recreation: Mount Hood, the Snake River, Crater Lake, the Columbia Gorge, and the beautifully named Cascade Mountains. And then there’s the rain...lots of rain. The southwest coast of Oregon, one of the wettest regions in the country, can receive over a hundred inches of rainfall per year, and on any given winter day, it is more likely to rain than not.

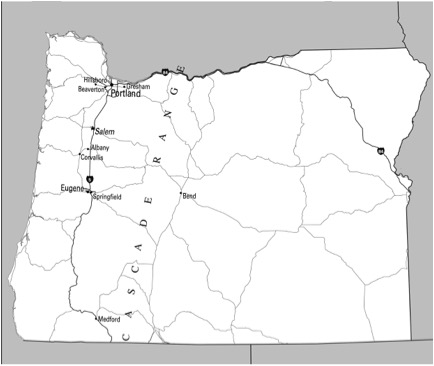

If the arid regions of the southwest part of the state are sometimes left out of descriptions of Oregon, it is perhaps because most of the people who live in the state live west of the Cascades. Nine of the state’s ten largest cities line up along Interstate Five, which threads its way in between the mountains and the ocean all the way from California to Washington along the...ahem...New Oregon Trail.

Pick a Theory

Oregon is unique among state names because even its language of origin is not entirely clear (i.e. there has been no consensus as to whether the word is Euro-American or Aboriginal-American), and thus any “meaning” has been blurred, distorted or entirely lost.

There is, however, no shortage of theories. Among the most popular is that the word Oregon is derived from the Spanish word oregano, referring to a spice (oregano, marjoram or sage) that grows wild in the northwest. The Spanish indeed explored the northwest coast in the late 1500’s, but there is no record that they referred to the region by the name Oregon or anything similar.

Another widely held theory is that the word derives from the French word ouragan meaning “storm” or “hurricane.” This idea stems from the belief that the Columbia River was once called the “River of Storms” by French traders.

Still another theory proposes that the word is connected to the Spanish word oreja meaning “the ear.” This one appears to derive from the big ears of the natives encountered by Spanish explorers. However, as one historian notes, “...the Spaniards themselves have left no record of the kind; nor has it been noted, so far as we are aware, that the ears of our Indians were remarkably large.”1

One more theory holds that the word is a corruption of “Aragon,” a province in Spain, the name of which might have been dropped upon the natives by Spanish explorers as a substitute for Spain and repeated to English and French traders up to a century later.

All of the above theories are contradicted by the fact that the first written instances of the word in any letters or publications found thus far indicate specifically that the word is Indian, not European. One of the only definitions that has arisen (until recently, as will be shown) as an aboriginal derivation is a Siouan word which means “a casket” or “plate of bark.” This definition, however, is also suspect being simply the result of looking up, in an early vocabulary for a particular tribe, a word that the compiler had spelled “Oragan.”

The Grease Trail

Efforts have been made in recent years to find a more plausible indigenous meaning for the word, and an article published in 2001 in the Oregon Historical Quarterly supplies a very likely candidate.

The article, “Ourigan: Wealth of the Northwest Coast” by Scott Byram and David G. Lewis, proposes convincingly that the word is derived from a kind of fish oil that was produced and traded by the coastal Indians of the Northwest in the 1700s (and, indeed, is still produced and sold today). The native word for the fish Thaleichthys pacificus, a variety of smelt, was ooligan, a name that is also applied to the oil which can be extracted from the fish. This oil, used for preserving food, waterproofing canoes, and even treating illnesses, was an extremely important trade good of several northwest tribes. It found its way eastward across the Rocky Mountains on what Byram and Lewis refer to as the “Grease Trail,” where it was traded to tribes of the northern plains.

The article even describes the phonetic transition from "ooligan" to "oorigan" or "ourigan":

“The western-most Cree speakers used the [r] sound in place of the [l], and thus [uligan], or ooligan, would have been pronounced [urigan], or oorigan.”

It was the Cree, as well as the tribes with whom they traded and fought, who, according to Byram and Lewis, conveyed the name eastward to French and Spanish explorers in the 1700s.

Which River?

In 1765 the word begins to appear in historical texts, in particular in letters of an English explorer named Robert Rogers. Rogers petitioned King George III in that year to explore the interior of North America by way of what he was sure would be the elusive Northwest Passage, or water route to the Pacific Ocean. In his request, Rogers specifically mentioned a river which he claimed the Indians called the “Ouragon.” His petition was denied, but in a subsequent petition seven years later, he referred to the same river, this time spelling it “Ourigan.” The route Rogers specified in his request, Byram and Lewis say, followed a trade route established by the western Cree. The conclusion then is that Rogers got his information directly from this native tribe or from the writings (or even possibly information transferred only orally) of someone else who had spoken with them. Rogers’ reference to this “Ourigan” River, which he also called the “River of the West,” is generally believed to be the first written instance of the word.

According to early scholar T.C. Elliot, it was Rogers who imparted the word “Ourigan” to Jonathan Carver. Carver, an Englishman, acted as cartographer for an expedition organized by Rogers and eventually gained fame as an explorer in his own right. After an extensive exploration of parts of what are now Minnesota and Wisconsin, Carver published a book in 1778 called Travels through the Interior Part of North America, which became vastly popular. In it he used Rogers’ spelling “Ourigan” to refer to a western river which he had learned of from natives during his explorations.

It has long been assumed that the Ourigan river to which Carver and Rogers referred was the Columbia. Captain Robert Gray, the first American to sail around the world, found and explored the Columbia River beginning in 1792. He named it for his ship, the Columbia Rediviva, and his explorations would become the basis for the American claim to the region. Byram and Lewis, however, matched descriptions and latitudinal coordinates given by Rogers more closely with the Fraser River, which runs through Canada’s British Columbia. Regardless, it is probable that, even given the popularity of Carver’s book, the name “Oregon” was not widely used in 1792, given that Gray did not, apparently, even consider using that name for the river he found.

Still, when Lewis and Clark, and vicariously Thomas Jefferson, explored the northwest in 1804-06, they referred only occasionally to the Oregon River. Maps of the time, which were largely based on scant explorations of the coast combined with information gleaned from native tribes of the northern plains, often depicted both a Columbia and an Oregon River.

Nova Albion

As for the name of the land, Spaniards, of course, referred to it as part of California (a fate worse than death for some modern-day Oregonians), and staked their claim on the basis of explorations by Greek navigator Juan de Fuca in 1592 and Spanish explorer Sebastian Vizcaíno in 1603. These explorers, however, who were primarily interested in finding a water route across the continent, rarely got out of their boats to look around, much less to establish any kind of settlement or colony.

The most universally recognized claim to the Pacific Northwest was England’s by virtue of the clandestine 1577-1580 circumnavigation of the globe by Sir Francis Drake. During this voyage, Drake landed on the northwest coast—though the exact location of this landing is the subject of heated debate among regional historians—and named the land “Nova Albion.” “Albion” was a common reference to England, and can be traced to times when the Romans occupied the British Isles. The word is derived from the Latin albus or “white,” and referred to the white cliffs which are prominent on the south-east coast of England, and which at least one of Drake’s crewmen noted on the western coast of North America as well. After Drake’s voyage was made public, the name “Nova Albion,” or “New Albion,” was commonly used on maps—even occasionally on Spanish maps—to name what is now Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia.

Drake was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1581 upon the ship in which he had made his famous voyage, the “Golden Hind.” Even though Drake’s name for the region didn’t stick, it is perhaps fortunate that he did not choose to use Gray’s method of naming the land after his sailing vessel!

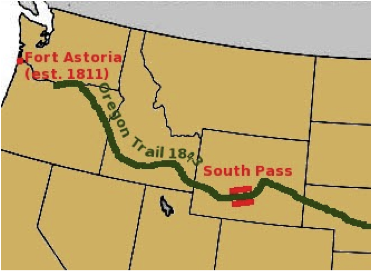

Very shortly after the Louisiana Purchase, even before Lewis and Clark returned from their journey, Americans began to move westward and encroach upon New Albion. In 1811 John Jacob Astor financed a venture which consisted of two expeditions, one by land, the other by sea. On behalf of his American Fur Company he sent the ship Tonquin around Cape Horn to Vancouver Island. Its crew then established Fort Astoria on the banks of the Columbia River. He also sent an overland crew, only some of whom survived the grueling journey to make it over the Rockies to Fort Astoria.

Hostilities between the Americans at Fort Astoria and local natives, as well as with the British once the War of 1812 had begun, caused the ultimate failure of Fort Astoria. Several of its founders, led by Robert Stuart, abandoned the site and began the long journey east over the mountains. In October of 1812, having almost starved to death along the way, this small band of men discovered the South Pass, a route through the intimidating Rocky Mountains which was substantially easier than had as yet been found. When they returned, they reported this route to Astor who considered the information about the South Pass proprietary, and was able to keep it secret for twelve years.

In 1824 the South Pass, a wide valley that interrupts the craggy peaks and ridges of the Rocky Mountains in what is today southern Wyoming, was rediscovered by Jedediah Smith and made public. This revelation would lead the way to increasingly larger waves of settlers over the next three decades into Oregon and northern California. Eventually this route, from the east—usually beginning in St. Louis—to the northern Pacific coast, became known as the “Oregon Trail.”

Grass Roots

In 1817 William Cullen Bryant, then a completely unknown poet, published his breakthrough work “Thanatopsis[ 1 ].” By this time the great river in the Northwest was commonly called the Columbia on maps and charts, but Bryant had read his Jonathan Carver and chose to use “Oregon”:

“ ...Or lose thyself in the continuous woods,

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings—yet the dead are there...”

The poem, a solemn, hundred-line piece about the marriage of nature and death, which Bryant had written when he was only nineteen years old, became vastly popular, as did Bryant himself. He went on to become an editor of the Saturday Evening Post, and a famous abolitionist, who had some influence on Abraham Lincoln. Perhaps less importantly, he also had some influence on the word “Oregon.”

Within a year after the publication of Bryant’s poem, a school teacher and writer in Massachusetts named Hall Jackson Kelley began to zealously advocate the exploration and settlement of the Northwest. In 1829 Kelley was instrumental in creating the “American society for encouraging the settlement of the Oregon Territory” and went on to write books and pamphlets reflecting his enthusiasm, among them “A Geographical Memoir of Oregon,” which strongly advocated populating what was more and more frequently referred to as “Oregon Country.”

Meanwhile

In 1818, in order “...to prevent disputes and differences amongst themselves,” the United States and Great Britain agreed to jointly occupy the country “...on the North West coast of America, westward of the Stony Mountains....” No name was given to the land which was still very sparsely populated by whites. The agreement, which was originally intended to last only ten years, was extended indefinitely in 1827.

In 1819 the U.S. signed a treaty with Spain that set the northern border of California (i.e. Spanish Territory) at the 42nd parallel, the modern border between California and Oregon. Within two years, bills began to be submitted to Congress for the formation of a new territory. The first was proposed byJohn Floyd of Virginia on January 18, 1822, and named the potential new state “Origon Territory.” The politics of the next three decades with regard to this region have filled fat history books, but it is clear that by 1822 the name “Oregon” (though a correct spelling was not yet agreed upon) was the decided favorite, at least to Americans, for what they were sure would eventually become a U.S. territory.

On May 2, 1843, a provisional government was established at the town of French Prairie by American fur traders and other civilians for the independent “Territory of Oregon.” The leaders of the movement were initially divided over whether they wanted independence or annexation by the United States. The quest for annexation ultimately prevailed, and the aforementioned provisional government went into effect. On June 15, 1846, the Treaty of Oregon was signed between the U.S. and Great Britain establishing the 49th parallel as the now continuous border between British Canada and the U.S. On August 14, 1848, the U.S. created Oregon Territory, leaving much of the provisional government intact. Oregon then became a state on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1859. President James Buchanan signed the Act, making Oregon the thirty-third state to join the union.

End Notes

1. MacArthur, Lewis M., Oregon Place Names (Portland, 1944), p. 3.