OHIO

Tin soldiers and Nixon’s coming

We’re finally on our own

This summer I hear the drumming

Four dead in Ohio

—Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, Ohio

Q: What’s round on both ends, and hi in the middle?

A: Ohio.

—Old Riddle

North, West, South, or East

Despite the fact that Ohio is named for the “beautiful” river that creates its southern border, the state’s name often conjures up images of industrialization, steel and rubber factories, and smokestacks piercing the horizon. And Ohio’s city names may be even more evocative of the blue collar ethic that fuels such gritty development: Dayton, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus, etc.

Up until the 1970s Ohio was known more for the pollution of its rivers than for their beauty. The PBS series The States discusses the many fires that burned on the Cuyahoga River, fires that were fueled by the sheer tonnage of pollution in the river. These conflagrations, it turns out, had a silver lining. Because of the dramatic dumping of toxic waste into the state’s waterways, the environmentalist movement was galvanized with the federal Clean Water Act and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. The rivers of the state were cleaned up, and Ohio could once again take pride, knowing that its namesake once again represents nature’s beauty and not man’s folly. We owe a humble thanks for these new ideas on the environment.

PBS also reminds us that Ohio calls itself the “Mother of Presidents,” having provided eight of our nation’s leaders. But given who those eight were, it may not be a title Ohio truly wishes to embrace:

-

William Henry Harrison gave his inaugural speech on a cold, rainy day and died of pneumonia only thirty-two days later.

-

Ulysses S. Grant led the Union to victory over the South in the Civil War, but is known for running one of the most corrupt presidential administrations in history.

-

Rutherford B. Hayes lost the popular vote in 1876, and only took office after a compromise was reached wherein he agreed to end the military occupation of the southern states, thereby putting an end to reconstruction, in return for the Democratic party acknowledging the assignment to Hayes of twenty disputed electoral votes.

-

James Garfield was the second president to be assassinated while in office after Lincoln.

-

William McKinley became the third president to be murdered in office. (Being killed while in office is, of course, not their fault, but it does lend itself to a rather morose legacy.)

-

Benjamin Harrison is most famous for presiding over the first peacetime U.S. government to appropriate more than a billion dollars. Harrison, a Republican who supported high tariffs, increased spending on government pensions and education, and who signed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act into law, was defeated by Democrat Grover Cleveland who campaigned on a platform of decreased government spending and lower taxes.

-

William Howard Taft was, famously, the fattest president we have ever had.

-

Warren G. Harding presided over another one of the most corrupt administrations in U.S. history, including the Teapot Dome scandal which might have led to his impeachment if he hadn't died while in office .

Ohio is also known for its farmland and its football. While the cities of Ohio convey an industrial theme, a little over half of Ohio’s land is farmland. And one thing that both the city dwellers and rural folk can agree on is a passion for their football teams: the Hawkeyes and Buckeyes, the Browns and the Bengals—all can claim an enthusiastic base of proud Ohio football fans.

Ohio was the first of the states formed out of the Northwest Territory. It sits in the far southeast corner of that massive tract, won by the U.S. after the American Revolution. Its norther border is south of all of the other states carved out of the Northwest Territory. To westerners, Ohio is “eastern,” and to southerners it is “northern,” all the while remaining the easternmost of the “Midwestern” states. Make sense?

The Iroquois

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the French explored much of the eastern coast of Canada and the St. Lawrence River, and established trading posts in order to obtain valuable furs from the Indians of the region. The French, under Samuel de Champlain, allied themselves with the Hurons, long-time enemies of the Iroquois. The Iroquois, whose native land was in the region of New York State, began trading with Dutch settlers, eventually obtaining muskets and iron tools from them in order to effectively battle their Indian enemies as well as the hated French.

Around 1650 the Iroquois (or, more accurately, the Europeans who traded ravenously for furs) depleted the supply of fur-bearing animals in the area they inhabited, and so moved south and west to the lush Ohio River Valley. Using their newly obtained weaponry, they easily overtook the indigenous tribes of the region, tribes who were already weakened from diseases which had been spread to them by European explorers and missionaries. In what came to be known as the “Beaver Wars” because of the beaver and deer pelts so coveted by the aggressors, the Iroquois easily defeated and pushed out Ohio’s native tribes and claimed the land for the Iroquois Confederacy—not for habitation but for hunting and fishing.

The River

“Ohio,” the Iroquois word for the river which ran through the region they now dominated, was thus adopted by Europeans. The meaning of the word is mildly disputed. The French, who continued an adversarial (to put it gently) relationship with the Iroquois, translated Ohio into “La Belle Rivière”—”the Beautiful River.” Historian R. E. Banta interprets the French translation further: “Not a beautiful river, mind you, but the beautiful river, with no fear that it might be confused with any other.” Banta goes on to say that the French may have misunderstood the exact meaning of the Iroquois word. Later linguists have translated Ohio as “The Great,” “The White” or “The Sparkling.”1

Given old and current descriptions of the Ohio River, the French translation seems entirely appropriate. But more than being a beautiful river, the waterway, its banks, and the valley in which it is situated—called informally “Ohio Country” until the end of the Revolutionary War—was a strategic jewel for the Indians, the French, the British and the Americans. Not surprisingly then, the beautiful Ohio River and the region to its north and west were the sites of battles, skirmishes and grisly massacres for many years to come.

The river began to appear on maps around 1669, and descriptions of it renewed widespread anxiety that a trade route to the Orient might yet be found. Renè Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle explored the Ohio River, but whether or not he was the first European to do so is a matter of speculation.

The Territory

When the Ohio Country became a territory, it was not called “Ohio Territory.” It was referred to instead as the “Northwest Territory,” and included what is now Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois. The Northwest Territory was created after the American Revolution out of lands ceded to the United States by Great Britain. The question of what to do with those lands was being answered, however, while the war was still in progress, by a resolution adopted by Congress on October 10, 1780:

Resolved, that the unappropriated lands that may be ceded or relinquished to the United States, by any particular states...shall be disposed of for the common benefit of the United States, and be settled and formed into distinct republican States, which shall become members of the Federal Union, and shall have the same rights of sovereignty, freedom and independence, as the other States...2

The lands referred to were, at the time, claimed by the British, the Indians, and even by some of the original colonies, like Virginia and Pennsylvania, whose original charters included lands “from sea to sea.” After the war, the defeated British relinquished their claim on the territory. The Indians, who had for the most part sided with the British during the conflict, were coerced into giving up the Northwest Territory based on the American claim to have defeated the British and their Indian allies.3 Congress attempted to cloak its coercion in legality by signing dubious treaties with several of the Indian tribes, but the reality for the future would be a bloody struggle between Indians and settlers.

In 1787 Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, a document whose significance in U.S. history rivals that of the Constitution. It formalized the 1780 resolution, allowing new lands to be formed into territories and then equal states, rather than satellite provinces of the Union.

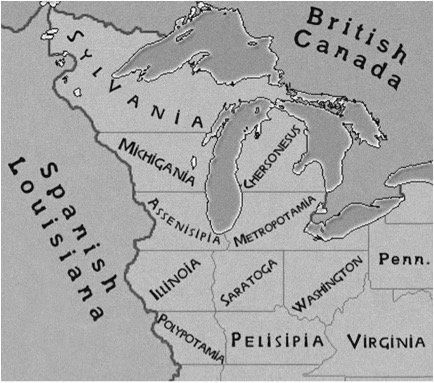

Thomas Jefferson was one Founding Father who was actively attempting to design a procedure for organizing the Northwest Territory into American states. In the now-famous Jefferson-Hartley map of the region, he not only divided the land into fourteen new states (some historians interpret it as up to seventeen), he proposed names for them as well. Sylvania, Michigania, Metropotamia, and Chersonesus were among the classical names proposed, and they sound kind of silly to our twenty-first century ears. But in truth, they were no more silly than, say, “Indiana” or “Montana.”

One other name that Jefferson proposed was “Washington,” in an obvious homage to our first president. It was actually inserted as one name for what would be the first territory created when the Northwest Ordinance was being debated in Congress. But when it actually came time to break up the Old Northwest, “Washington” was replaced with “Ohio” in the eastern, most populous region, and “Indiana” became the name for the remaining territory in the west. Washington became a county of the sixteenth state and remains so today.

The Seventeenth or the Forty-Eighth State?

For over a century Ohio’s statehood, or more accurately, the date on which statehood was conferred, labored under the most extreme confusion. One writer, a former Governor of Ohio, James Edwin Campbell, makes a convincing case in one article5 for five different dates upon which Ohio could have entered the union, none of the five contradicting the others. His point, which comes through loud and clear, is that when Ohio was being populated, largely by former soldiers from the Revolution, there was no clear procedure for new areas to be granted statehood. The Northwest Ordinance proclaimed it possible but did not lay out a definitive process.

Therefore, Ohio’s statehood could be asserted as any of the following:

-

April 30, 1802, the day the Continental Congress passed the Enabling Act authorizing Ohio to elect representatives and draw up a constitution.

-

February 19th, 1803, when President Jefferson signed an act approving Ohio’s constitution and boundaries.

-

March 1st, 1803, when state officials were inaugurated and judges were appointed.

-

March 3rd, 1803, the date Congress reviewed and accepted revisions to the state constitution of Ohio.

-

Or last, but not least, on August 7, 1953, when Ohio Congressman George H. Bender introduced a bill in Congress, specifically to admit the state of Ohio into the Union.

The last one, while odd, is actually true. In 1953, the year of Ohio’s sesquicentennial, a rider on horseback delivered an act to Congress in Washington D.C., which accepted the statehood of Ohio retroactive to March 1st, 1803 (the date most commonly agreed upon as the date of Ohio’s admission into the Union as the 17th state). It was signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

End Notes

1. Banta, R. E., Rivers of America: The Ohio (New York, 1949), p. 8.

2. Knepper, George W., Ohio and Its People (Kent, 1989), p. 47.

3. Knepper, p. 51.

4. Penny, Jordan, “248 – Friends, Polypotamians, Countrymen!,” Strange Maps , http://strangemaps.wordpress.com/2008/02/25/248-friends-polypotamians-countrymen/, accessed 9/15/09.

5. Campbell, James Edwin, “How and When (?) Ohio Became a State,” Ohio History , vol. 34, p. 29.