NORTH DAKOTA

[Dakota] is a name at once suggesting greatness and broad domain. And a careful review of its history must satisfy one that a substitute should never be given. And it is no wonder that the people throughout the length and breadth of the Territory, as with one voice said: “Let them bear the ancestral name! A name whose every letter seems an unwritten chapter in the history of that powerful nation, from whose hands we adopted her; with all the legends, wild romances and fascinating traditions—an ancient jeweled-chain—which must be kept: A legacy for her children.

—Frances Chamberlain Holley,

Once Their Home: Our Legacy From the Dahkotahs

“Don’t come, unless you’re prepared to stay.”

—Garrison Keillor on North Dakota

It Can’t Snow All the Time

When you think of North Dakota and its continental climate location, it is difficult to picture anything else but snow. Not only does it snow—and a lot!—but once the snow arrives in late fall, North Dakotans can expect it to stick around until spring. Maybe it’s the ice storms or the polar fronts, the blinding blizzards, or the blood-drenched snow of the infamous wood chipper scenefrom the 1996 Oscar winning film “Fargo”; but whatever the mental image, if there’s snow involved, North Dakota probably isn’t very far from your mind.

Summers in North Dakota can also exhibit the drastic variations created by the continental climate, yet are typically mild and receive ample precipitation. This summer weather, joined with vast, fertile soil, permit North Dakota to be the country’s largest producer of barley, sunflower seeds, and durum wheat. In fact, in the summer months, the rolling snow-covered prairies are transformed into seas of bright burnt yellow, as sunflower farms take over the land. North Dakota truly is a perfect example of the beauty of nature’s climactic extremes.

Aside from the obvious—weather, agriculture, the widely popular progressive radio phenomenon The Ed Schultz Show—North Dakota is also (uncommonly) known for its cuisine. Knoephla soup, lutefisk, Kuchen, lefse, Fleischkuekle—these are not genus classifications for prehistoric organisms or the names of small, blink-through towns in unfamiliar European countries. They are in fact popular dishes of German and Scandinavian cuisine. In the late nineteenth century, the territory of North Dakota experienced an influx of Scandinavian immigration that has shaped, molded, and simmered the modern North Dakotan culture.

Moving

It is not difficult to trace the word “Dakota” to its origins. What is more difficult is tracing the application of the word to the land it now names, for it is not as simple as saying that the two states bearing the name “Dakota” were so called because they were inhabited by an Indian tribe of that name. In fact, before any European had met a Dakota Indian, they had a different name for them, a name that would describe them, their brethren, their language, and the language of many other tribes in North America.

The French, who in the early 1700s first explored the western Great Lakes region, traded among and were allied with the Chippewa Indians who were concentrated in northern Michigan and Wisconsin. The Chippewa, sometimes called Ojibwe , spoke an Algonquian language and were in the precarious position of being surrounded by enemies. To the north and east were the Iroquois, a powerful, dominating foe, in part because they obtained guns through their trade with the Dutch. And to the south and west were the people they called “naudiwisiweg” meaning “little snake” to differentiate them from the more awesome Iroquois. The French recorded the name as “naudiwisioux” and later shortened it to simply “Sioux.”

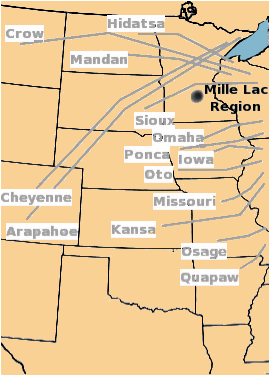

When ethnologists began classifying Native Americans by language, they discovered that the Siouan language was spoken by tribes all over central North America. The still-accepted inference is that wherever and however the Sioux people began as a culture, several groups divided from them before or during their move westward from the east coast of North America. Some moved south and became the Iowa and Kansa tribes, while others moved north and further west and became the Mandan and Hidatsas. The main group of Sioux moved west along the southern edge of the Great Lakes through Michigan and Wisconsin to Minnesota.

The Sioux, it turns out, were a highly organized nation of people. They trace their history (though not necessarily their origins) to a time just before the arrival of Europeans. During this era, the early 1500s, they lived mainly in the east between the Appalachians and the Atlantic. If they weren’t already rather nomadic (and indications are that they were), the coming of the white man caused them and virtually every other group of people living in North America to move, and move a lot. By the 1700s, before they had even seen a European, the Sioux were living in the Mille Lac region of Minnesota, though some groups had broken off and become enemies of their former tribe. The Sioux referred to them as hohay or “rebels,” and it was several of these tribes—the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Assiniboin—who would dominate central and northwestern North Dakota.

Allies

The Sioux called themselves Oceti Sakowin or “Seven Council Fires,” referring to the seven divisions of the nation. These seven divisions are grouped by the three similar dialects they speak. Four of the Council Fires are Santee Sioux who spoke the Dakota dialect. Two are Yankton Sioux, and spoke Nakota. The third and largest by far is the Teton Sioux group who spoke the Lakota dialect. The dialect is important in distinguishing between the three divisions, and often the tribes would refer to themselves by the language they spoke. As is indicated in the names of the dialects, often words were identical for each dialect except for the substitution of the letters d, l, and n. Thus the word for “thank you” in Dakota is pidomiye; in Nakota it is pinomiye; and in Lakota the word is pilomiye.1

Painting by Karl Bodmer

The word Dakota (as well as Nakota and Lakota) means “ally,” but is often translated as “friend”. “Ally” is more appropriate, however, because while all of the members in the seven councils became increasingly different in their culture and lifestyle, they remained allied with each other and had many common enemies, not least of all the encroaching Europeans.

Of the three, the Lakota became the tribe that epitomizes the stereotypical Plains Indian of American folklore. They took advantage of the newly introduced beasts of burden brought over by the Spaniards in the early 1500s—horses. They moved onto the prairies, became extremely nomadic, lived in easily-moved teepees, wore headdresses of feathers, were expert horsemen, hunted buffalo, and were fiercely defensive of their territory, especially with regard to white men. The Lakota dominated the Missouri River in what is now South Dakota and also hunted the southwest corner of North Dakota.

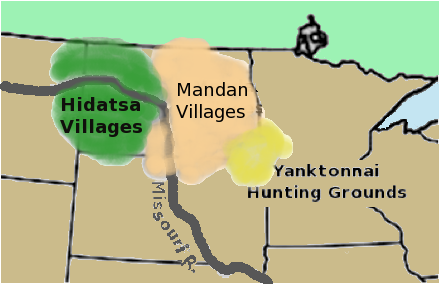

The Yanktonnai, a division of the Nakota Sioux, lived and hunted in southeastern North Dakota. In the central part of the state, however, the place where the Missouri River turns west, were the permanent villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes. These villages were well known trading centers, frequented by the French, and known to Americans by the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition. In fact, once the Louisiana Purchase created a new frontier for the U.S., the northern section of it was frequently referred to as “Mandan Country.”

Ironically, the Dakota were the only division of Sioux who did not migrate into what are now North and South Dakota. The Santee, or Dakota Sioux, were less nomadic than their brethren. When the Chippewa forced them from the Mille Lac region in Minnesota, they moved south only a short distance to the Minnesota River, maintaining their woodland and agrarian ways, and relying little, if at all, on the buffalo of the plains. While they defended their territory, the Dakota were also less warlike than the Lakota and Nakota and were therefore better known to the Americans who quickly moved into the region following the purchase of Louisiana.

For, this reason during the first half of the 1800s, the name Dakota was often used to refer to the entire Sioux nation, a legacy that has largely endured to this day. But the region that would become Dakota Territory did not yet have a name and was certainly not yet called “Dakota.” In fact, the word, while not completely obscure, was not by any means ubiquitous. In his journal in 1803, William Clark wrote “This great nation, whom the French have given the nickname of Sioux, call themselves Dakota-Darcotar.”2 The fact that Lewis and Clark felt compelled to report this indicates that the name Dakota was not entirely familiar to them, nor to those to whom they were reporting.

The Dakota Land Company

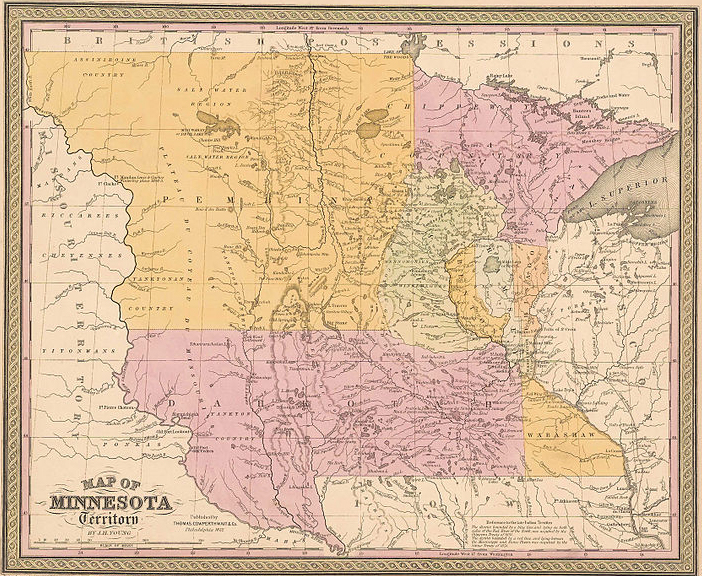

In March of 1849, Minnesota was given territorial status with borders that extended to the Missouri River, which is to say, it included half of what are now the states of North and South Dakota. A few short months later, the county of Dakota was formed in Minnesota Territory, the name taken from the Indians who in fact occupied much of the land at the time. The county included the bustling city of St. Paul and extended westward all the way to the western territorial boundary. This was undoubtedly the first point at which North and South Dakota could claim their name; however, four years later the county was divided up, and Dakota County Minnesota shrunk to a few square miles surrounding the city of St. Paul.

The connection between the county and the future states, however, would continue. In the 1850s it became clear that the imminent statehood for Minnesota would involve lopping off the western portion at the Red River. On May 23, 1857, a group of St. Paul businessmen who saw the handwriting on the wall were granted a charter by the Minnesota territorial legislature “with full powers for the purchase and entry of lands and the establishment of townsites.”3 They called themselves the Dakota Land Company, and though they were formed in Dakota County, Minnesota, their object was the land west of the Red River Valley, which would be left out of the new state once it was admitted. They sent a group of settlers to form a township on the Big Sioux River, but when they arrived, they found a town already established. The Western Town Lot Company of Dubuque, Iowa, had beaten them to the punch only weeks earlier and had claimed the choicest spot on the river, which they named Sioux Falls. Not to be outdone, the Dakota Land Company simply claimed the adjoining 320 acres and called their township Sioux Falls City.

The motivation of The Dakota Land Company is critical. While most of the history books allude to it, one book asserts rather blatantly that “from its very beginning the company was a financial venture of the Minnesota Democratic Party.”4 The goal of the company, then, was to gain territorial status for the region, and insert its own members as delegates and government officials, giving the Democrats complete control over a huge new territory, as well as more power in congress. The actual settlement of the land was secondary. Put another way “The Dakota Land Company...attached more importance to political organization than to immediate growth.”5

This point is rather pointedly illustrated by the story of the first territorial elections held in the region. Once Minnesota achieved statehood in May of 1858, the thirty or so citizens of Sioux Falls determined to form a legislature, thereby sending a message to Congress of the need for governmental organization. And so that there could be no confusion about who was putting forth the effort to organize the region, the Dakota Land Company began referring to it as “Dakota Territory” and organized the elections rather creatively:

...on the morning of election, the whole population organized into parties of three or four, elected each other judges and clerks of election, and then started off with their teams in various directions for a pleasure trip, and whenever a rest was taken, which occurred frequently, an election precinct was established, and the votes not only of the party but of their uncles, cousins, relatives and friends were cast, until as a result of the election the total vote rolled up into the hundreds, and was properly certified to.6

Similar antics of the Dakota Land Company are rampant in the history of the territory. Between 1858 and 1861 its agents formed “paper towns,” reported on phantom surveys, and began their own newspaper— The Dakota Democrat —which routinely reported the grossly exaggerated population of the area. A few short months after the “election” of 1858, an agent of the Dakota Land Company named Alpheus G. Fuller, who had been chosen to represent the territory to the U.S. Government, appeared before Congress declaring himself the delegate from the “Territory of Dakota.”

Late in 1860 a bill was introduced to organize a portion of the region along the Red River into the Territory of Chippewa . The request for this organization came from the citizens of Pembina, an old trading town near the Canadian border, and the only concentrated non-Indian population (though many of the residents were part Indian) in the northern section of the region. This bill failed, but the following year, under the guidance of the now Republican administration in Washington, the Dakota Territory was finally formed out of what are now North and South Dakota and the entire state of Montana.

The Rest of the Story

While the Dakota Land Company had failed in its political goals (i.e. making North Dakota a new territory safe for the Democratic Party), it had succeeded in imprinting upon the region the name which it would carry to statehood. Like most state names, the spelling of the word would not be finally settled upon for decades. Dacota, Dacotah, and Dakotah all appear in the Territorial Papers—in bills and memorials to Congress as well as various correspondence and newspaper articles, and often one document would contain different variations of the spelling. But the name was settled upon, and the work toward statehood now commenced in earnest.

Statehood, of course, involved division, and so the rest of the story of the naming of the Dakotas will be told in the chapter on South Dakota.

End Notes

1. Tweton, D. Jerome and Theodore B. Jelliff, North Dakota: The Heritage of a People , (Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1976), p. 16.

2. The Journals of Lewis and Clark , Chapter 1, Setting Forth, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/JOURNALS/LEWIS.html, accessed 7/25/09

3. Schell, Herbert S., Dakota Territory During the Eighteen Sixties (University Research Fund, 1954), p. 11

4. Lamar, Howard Roberts, Dakota Territory 1861-1889 (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1956), p. 42.

5. Schell, p. 12.

6. Baily, Dana R., History of Minnehaha County, South Dakota , (Sioux Falls: Brown & Saenqer, Ptrs., 1899), accessed at http://files.usgwarchives.org/sd/minnehaha/history/bailey/chap1.txt, 7/25/09.