NEW YORK

I want to be a part of it: New York, New York

— Liza Minelli and/or Frank Sinatra

New York, New York

“…it appears, I say, and I make the assertion deliberately, without fear of contradiction, that this globe really was created, and that it is composed of land and water. It further appears that it is curiously divided and parceled out into continents and islands, among which I boldly declare the renowned island of New York will be found by any one who seeks for it in its proper place.”

—Washington Irving,

Knickerbocker’s History of New York

“Hey there Delilah, What’s it like in New York City?

—Plain White T’s, Hey There Delilah

New York…State

“New York” refers to New York City. Whereas the phrase “New York City” is almost redundant. If one wants to refer to the state of New York one generally does so explicitly: “New York State.” Not only does “New York” refer to New York City, it refers to Manhattan, otherwise known as “The City.” Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens and Staten Island are all spoken of separately, with their own brand of provincial pride.

There are, of course, those who might take offense at this generalization. What about Albany? Syracuse? Cooperstown, for heaven’s sake! What about Niagara Falls, the Adirondacks and the Catskills? All are readily and indelibly associated with the state of New York—but there’s that word again...“state.” Take it away, and what you have is a reference to possibly the most recognizable, the most identifiable place name in the country. And it’s not a state.

Such is the blessing and the curse of sharing your state’s name with perhaps the most famous city in the world. “New York” immediately sends one’s mind to a tiny island covered in slabs of cement, colorful lights, and just over eight million people. For some it stirs the soul with yearning for the cosmopolitan culture, the excitement of its frenetic pace, the endless possibilities for human connection and activity, and for others it evokes fear of crime, terrorism, and simply getting lost in the ocean of people ebbing and flowing through currents of life like the water of its surrounding rivers.

But whatever one’s impressions of New York—the state or the city—the words are imbued with perhaps the most emotion-provoking of any state’s name. Love it or hate it, fear it or long for it, the feelings are strong and the images crystal clear.

The Dutch

Few stories in American history are as famous as the quaint little anecdote about the Dutch Royal Governor Peter Minuit buying Manhattan from the Indians for sixty guilders or twenty-four dollars. Nowadays, however, historians spend more energy debunking this story than teaching it. They point out that the value of the trade goods has been massively skewed and cannot even be known for certain since no deed or bill of sale has ever been found. They observe that the source of the story is one line written in a letter to the officers of the Dutch West India Company (which had organized the colonization of New Netherlands), a letter which wasn’t even discovered until 1846. And they note that the natives from whom Minuit purchased the land were the Canarsees who lived in modern Brooklyn and not the Weekquaesgeeks who actually inhabited the island of Manhattan.

Still, the kernel of truth in the story reminds us that New York was originally New Netherland, and that New York City was, naturally, New Amsterdam, and that the colony was the only one of the original thirteen that did not begin as an English holding . The Dutch claim to the land came courtesy of Henry Hudson, an English adventurer who sold his services to the Dutch who, like everyone else in the world, were interested in finding a water route through the massive—and massively inconvenient—obstructions that are North and South America. Hudson, of course, failed. But his attempt during the summer of 1609 gained for the Dutch a solid claim to part of what the English were already calling “Virginia.”

The name “New Netherland” was first used in 1614 in a document organizing a group of independent Dutch fur traders who were collectively given a monopoly on trade in the region between the Connecticut River and the Hudson River. By 1624 the Dutch West India Company had supplanted the New Netherland Company, and they began to colonize their holdings in North America which now extended further south to Delaware Bay.

In 1626 Peter Minuit took over as Royal Governor of New Netherland and very quickly made his famous “purchase” of Manhattan (an Algonquian word meaning “hilly island”). In order to mitigate the danger of Indian warfare, he then consolidated all of the Dutch settlements onto this tiny island with its most agreeable bay, and called it New Amsterdam. The Dutch fur trade flourished in the 1630s, but the 1640s saw a series of Indian conflicts which in 1647 prompted the installation of a new governor, the one-legged Calvinist governor-extraordinaire, Peter Stuyvesant. Stuyvesant managed the colony for seventeen years, overseeing a huge increase in its population, but he may be more famous for surrendering it to the English in 1664.

Meanwhile, back in England...

While the Dutch were busy colonizing New Netherland, the English were consumed with Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s rise to power. But it did not go unnoticed in London that the Dutch and their powerful navy were complicating trade for England by disregarding Parliament’s Navigation Acts. These laws forbade the American colonies from trading directly with foreign merchants, requiring instead that all trade pass through England on English ships. Despite this the English Parliament was on generally good terms with Amsterdam during the Commonwealth years.

Upon Cromwell’s death, the Parliamentarians lost their forceful leader, and the Royalists saw their chance. In 1660 the English throne was restored to King Charles II. Charles, whose father King Charles I had been executed by the Parliamentarians following the English Civil War, made a triumphant return to England to assume the long-vacant throne and with him was his younger brother James, who was promptly made Duke of York and Albany.

Old York

York was, and is, a prominent and richly historical city in northern England. Its history (as well as its name) dates back to A.D. 71 when the Romans established a military stronghold at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss. They called their fortress Eboracum, probably derived from the Celtic personal name Eburos, which many believe was further derived from the ancient British word for the yew tree. The yew, a conifer with a reputation as a resilient, long-lived tree, was sacred to the Celts and can still be found in the churchyards of some old English villages.

When the Anglo-Saxons invaded the British Isles in the sixth century, they made Eboracum, with its walled fortress, the capital of the region, but they confused the Celtic word Eborus for their own word Eofor, meaning “wild boar.” They attached the suffix -wic, meaning “place,” and the name thus became Eoforwic or “wild boar place.” When the Norwegian-Irish Vikings settled in the area in the 900’s Eoforwic became Jorvik. The Vikings used Jorvik to refer to their entire kingdom in northern England, and only a few short centuries later, Jorvik morphed into York. The English suffix -shire was added to describe the county that had been the Viking kingdom, and so we have the English city of York in the county of Yorkshire.

The Dukedom and the Duke

In the fourteenth century the tradition began among English royalty of bestowing the Dukedom of York upon the second son of the monarch, which brings us back to Charles II and James (later James II & VII) , the first and second sons of Charles I.

Though amazingly forgiving of those who had executed his father, Charles II wasted no time asserting his authority and escalating tensions with the Dutch by giving to his little brother all the land in America between the Connecticut and Delaware Rivers. Now, it’s not as if they didn’t know that the Dutch had long-since claimed and colonized that particular chunk of North America. Indeed the borders were chosen specifically to match those of New Netherland and in fact overlapped a royal charter which had previously been granted to John Winthrop Jr. of Connecticut. Thus, the king and his kid brother were announcing to Amsterdam their claim to Virginia...all of Virginia, and had the Dutch taken the announcement seriously the most recognizable place name in the country might now have a Dutch, rather than English, origin.

(formerly Duke of York and Albany)

As it was, Peter Stuyvesant braced for an invasion by the English, but he was told by the West India Company leaders not to worry—the small fleet of English ships carrying about five hundred soldiers and led by Colonel Richard Nicolls was instead on its way to Boston to quiet the ever-troublesome Puritans. Stuyvesant was therefore wholly unprepared when Nicolls appeared off Long Island and demanded the immediate surrender of New Amsterdam. Stuyvesant was willing to fight, but the burgomasters of the colony, important land-owners and merchants who made up a kind of “city council,” agreed not only that the fight would be futile but that the terms offered by Nicolls were fair—indeed generous. They eventually convinced Stuyvesant to surrender, which he did on August 29, 1664, the day Richard Nicolls officially took control of the region in honor of his patron, the Duke of York, and the city and colony of New York were born.

As royal charters went, New York was a remarkably large region to have been offered in a single grant, but then New York was different, even then. It was the only charter which was not bestowed as a gift from the king but concocted as an international political maneuver. It was also the only grant of land which was already substantially populated by Europeans. The task, then, once the colony was secured, was not to colonize but to govern.

at its height in 1664

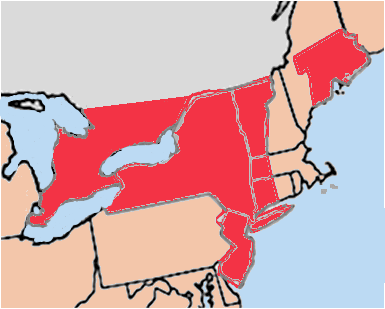

The borders of New York were unwieldy and far-flung, including not only the former New Netherland but all of Long Island (the northern half of which had previously belonged to Connecticut), the land west of the Connecticut River, eastern Maine, and the islands of modern Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. The largest change in borders happened before Nicolls even arrived in New Netherland. On June 24, 1664, James, Duke of York, bestowed upon two supporters, John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, the land south of the Delaware River which he named New Jersey. The borders with Connecticut were eventually settled by giving back to Connecticut most of the land west of the Connecticut River but keeping all of Long Island. This accounts for what now looks like a rather odd border, New York having only a few short miles of coastline on Long Island Sound but owning all of Long Island, which reaches northeastward nearly touching Connecticut.

The colony was already a thriving business center when the English took it, and that may explain the reluctance of the English governors to censure the Dutch or discourage their trade. Indeed, one of the reasons for conquering the province was its potential for wealth, badly needed (but in fairness, always badly needed) by the monarchy. James, Duke of York, became King of England in 1701, and the ducal proprietorship of New York was immediately converted to a royal province, but New York’s fortunes would quickly be tied to those of the other colonies.

By the time of the American Revolution, New York was one of the few colonies whose economy was robust enough to support the war. The city was already a metropolis (albeit by 18th century standards), and served as the nation’s capital for a short period after independence was declared.

On July 9, 1776, the New York provincial congress declared its independence from England. New York ratified the U.S. Constitution on July 26, 1788, making it the tenth state in the Union.