NEW MEXICO

“And away I did ride,

Just as fast as I

Could from the West Texas town of El Paso

Out to the bad-lands of New Mexico...”

—Marty Robbins, El Paso

"Texas? Real cowboys don’t come from Texas.

We’re from New Mexico."

— The Cowboys (1972)

Oh, Santa Fe

The New Mexico area has been part of the United States, part of Mexico, the Imperial Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain, and home to the Navajo and Pueblo Indians. Present day New Mexico reflects these deeply rooted histories in its culture and ethnicities. The dominant ancestry group is Mexican, which is nearly double the percentage of the second largest group—Native American. And both of these ethnicities are trailed by single-digit percentages of German, Spanish, English, and Irish.

The topography of New Mexico is breathtaking: towering mesas, endless mountain ranges, canyons, valleys, and infinite highlands. New Mexico truly is a beautiful place to live, and the vast openness and natural beauty make the state a Hollywood hotspot for filming. Motion picture classics like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid , Geronimo , and even Oklahoma! were all filmed in front of natural New Mexico backdrops, and the state has maintained film-maker popularity with more modern works such as Natural Born Killers , Superman , and Twins . Actors Bruce Cabot, Demi Moore, and Neil Patrick Harris were all born in New Mexico, but the surprise might come from another legendary New Mexican, John Denver. Mr. Denver, whose given name was Henry John Deutschendorf, Jr. was born—not in the Mile High City, nor in West Virginia—but in Roswell, New Mexico.

Santa Fe, capital of the “Land of Enchantment,” is a bustling hub of Mexican and Native American art, cuisine, and history and has accomplished the considerable feat of gaining respect as a cosmopolitan city without losing its cultural bedrock. The brilliance of Santa Fe has been captured by many world-renowned artists, but no artist is as closely associated with Southwestern interpretation as Georgia O’Keeffe. O’Keeffe, a Wisconsin-born painter, put New Mexico on the artistic map with her colorful expressions of stunning Southwestern flora.

Mexica

The name “Mexico” is derived from “Mexica” (Me-shee-ka), a people who migrated into the Valley of Mexico in the twelfth century. One tribe of the Mexicas, the Tenochcas, were initially a peaceful people who were reviled by the other tribes of the region for their ritual of human sacrifice (okay, perhaps not completely peaceful). The Tenochcas were forced into slavery by a dominant tribe of the area but proved unmanageable and were eventually released.

An abject people, they were constantly forced onto the worst lands of the area. According to legend, some time between 1300 and 1375 the Tenochcas wandered into the area of a large lake, where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus with a serpent in its talons. They believed this to be a sign, and they chose the area to build their own city, Tenochtitlan, or “place of the Tenochcas.”

Once settled, the Tenochcas fortunes changed and they began to dominate the region in a sinister manner, demanding tributes from neighboring villages and tribes, forcing them into servitude, and, most diabolically, using them for their continued practice of human sacrifice. When the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortes arrived in 1519, he used the enmity between the Tenochcas—now led by Moctezuma—and their neighbors to his advantage. The chieftains of the villages near the coast where Cortéz landed brought him tributes of gold and silver, and indicated that there was more where that came from to the west in Mexico—place of the Mexicas. These people who had been subjected to the cruel domination of the Tenochcas were only too willing to help the Spaniards conquer Moctezuma and destroy his grand city. Thus the European conquerors referred to the city and region of Tenochtitlan as “Mexico,” and after his conquest of that region was complete and the city devastated, Cortéz rebuilt it, continuing to refer to it as “Mexico.”

The Spanish expanded their domination of Mexico northward, now calling the vaster region Nueva España or “New Spain,” and defined separate provinces or kingdoms with their own regional governments. The northernmost region of New Spain was virtually unexplored, but an exciting first hand account by Cabéza de Vaca was reported to Antonio de Mendoza, governor of Mexico, in 1536. De Vaca had spent eight years wandering the American Southwest, along with a handful of other survivors of the Narváez expedition (see Mississippi). When de Vaca told of rumors of large cities in the north where precious minerals were traded, Mendoza became determined to find them, sending first Fray Marcos de Niza and then Francisco Vasquez de Coronado to explore the territory.

De Niza planted a cross at the Zuni pueblo in what is today New Mexico, and conferred upon the territory the name of “The New Kingdom of St. Francis.” Coronado spent two years from 1540 to 1542 looking for the vast wealth of the Seven Cities of Cibola which de Niza claimed to have found, but discovered only the pueblo villages of the Indians.

In 1563 Francisco de Ibarra explored the northern territory for two years. When he returned he claimed to have discovered “The New Mexico,” alluding to vast riches like those that Cortéz had found in Tenochtitlan, and once again reviving the hope of finding mineral wealth in the region. The name stuck, and the Spaniards began to place “Nuevo Mexico” on their maps as more and more expeditions were sent north in search of the elusive treasures.

Ironically...

The original Mexica Indians who migrated into the valley of Mexico and built the city of Tenochtitlan had come from the remote north. They called themselves Aztecs, meaning “people of Aztlan.” The particular location of Aztlan is unknown and widely believed to be a mythical city of origin for this tribe of once nomadic people.

According to legend, a feud arose between two sects of Aztecs—those followers of Huitzilopochtli, their god of war, and those who worshipped his sister, Coyolxuhqui. A civil war broke out, and the followers of Huitzilopochtli won. In his honor, they began to call themselves Mexica, derived from “Mexitli,” which was a title for Huitzilopochtli. It was, in fact, from this god that the Mexitli believed the sign of the eagle on the cactus was sent, prompting the building of Tenochtitlan. Ironically, while the location of the northern region from which the Aztecs originally migrated is not known, it is generally believed to be in the southwest United States—in or very close to…New Mexico.

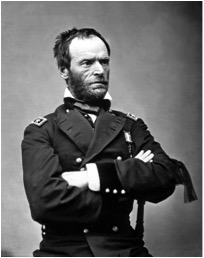

In 1848, centuries after the Spaniards had defined the province of New Mexico, the now autonomous nation of Mexico ceded the region to the United States in the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo which ended the Mexican-American war. The territory of New Mexico—consisting of what is now New Mexico, Arizona, and part of Nevada—faced a long delay in achieving statehood. The reasons were many and varied but generally derived from an ignorance of, and prejudice toward, the land and its people, the land being mostly desert and the people being predominantly Mexican and Indian. General William Tecumseh Sherman of Civil War fame once commented that the U.S. should declare war on Mexico and make it take New Mexico back!1

Among the proposals to counter this prejudice were periodic suggestions of new names for the territory—”Lincoln,” “Navajo,” and “New Andalusia” among them. Ironically, the reason for these proposed name changes was that the word “Mexico,” which had so inspired hope and dreams of wealth and prosperity for the Spaniards, was too suggestive of poverty and destitution for Americans.

Borders

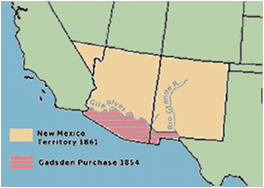

In 1854 James Gadsden, railroad promoter and American Minister to Mexico, attempted to rectify some confusion in the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo by placing the southern border of New Mexico Territory some thirty miles north of its original position. The loss would have cost the U.S. several thousand square miles, including the rich farmland of the Mesilla Valley and a potential site for a transcontinental railroad. Gadsden orchestrated the purchase of the land from Mexico for ten million dollars, cementing the southern border of the United States.

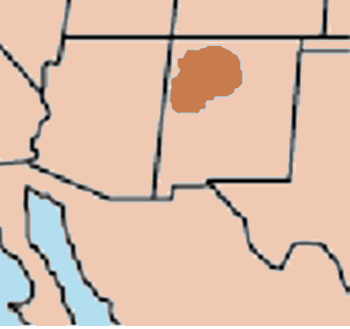

During the Civil War, New Mexico was divided into two separate territories—New Mexico and Arizona. This division, however, was not that which we know today. The region was split horizontally along the 34th parallel, the southern half taking the name Arizona. Both territories were governed briefly by Lieutenant Colonel John R. Baylor of the Confederate Army, who had conceived and decreed the division in order to appease the southern ranchers who were more sympathetic to the Confederate cause. But when New Mexico fell to the North after the decisive battle of Glorieta (referred to historically as “The Gettysburg of the West”), the territory resumed its original shape and name under Union control. Congress, now realizing that the region was in need of reorganization, took its own steps in dividing the territory. In 1863 the vertical division ofNew Mexico became official, with the new territory of Arizona being created out of the western half.

As previously mentioned, statehood was elusive for New Mexico. Opponents tended to be those wealthy land owners who benefited from having appointed officials rather than unpredictable elections. But also opposing statehood were people outside of the region who were prejudiced toward the aboriginal people there. One anecdote on the website for the New Mexico Genealogical Society illustrates how close New Mexico came to achieving statehood early on:

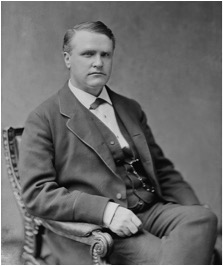

“ During an 1876 Congressional debate, Michigan Representative Julius Caesar Burrows, an admired orator, rose to speak in favor of a bill designed to protect the civil rights of freed Negroes. Stephen B. Elkins, New Mexico’s delegate to Congress, was not present for most of the speech, but entered the House chamber just as Burrows was bringing his rousing oration to a close. Unaware of the full nature of Burrows’ speech, Elkins shook his colleague’s hand in congratulations, a gesture many Southern Congressmen interpreted as support for the civil rights legislation. Elkins’ handshake is blamed for costing New Mexico several Southern votes it needed for passage of the statehood bill.”2

On January 6th, 1912, only weeks ahead of Arizona, New Mexico was confirmed as the 47th state of the Union. The statehood act was signed by President William Howard Taft who reportedly, after signing the legislation, looked at the distinguished and proud delegation from New Mexico and said, “Well, it is all over. I am glad to give you life. I hope you will be healthy.”3

End Notes

1. Simmons, Marc, New Mexico: A Bicentennial History , (New York, 1977), p. 133.

2. Torrez, Robert J., “A Cuarto Centennial History of New Mexico,” Official New Mexico Blue Book, Cuarto Centennial Edition, 1598-1998 , Office of the New Mexico Secretary of State. (also at http://www.nmgs.org/artcuar7.htm)

3. Torrez (accessed 10/2/09).