NEW JERSEY

‘cause nothing matters in this whole wide world

When you’re in love with a jersey girl

—Tom Waits, Jersey Girl

New Jersey Turnpike in the wee wee hours

I was rollin’ slowly ‘cause of drizzlin’ showers

—Chuck Berry, You Can’t Catch Me

Contradictions

New Jersey, or “Joisey” as the stereotype has it, owns a reputation as an industrial, blue collar arm of New York, a reputation rife with images of smokestacks, turnpikes, and organized crime. However unfair, these impressions are pounded out regularly in movies and pop culture, from Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront to new-age crime boss Tony Soprano, to the rough-hewn lyrics of Tom Waits and Bruce Springsteen. The characters and the stories, while irresistible on the screen, foil any possibility for the state to reconcile its image to its well-known nickname: the Garden State .

But then there’s Princeton —gorgeous, pristine, and utterly dignified Princeton. There’s Atlantic City—flashy, colorful, fun. And there’s the Jersey shore. (On the west coast one goes to the beach, but on the east coast one goes to the shore.) Once the images of factories and the mafia are swept away, the name New Jersey easily calls to mind the sound of the Drifters singing Under the Boardwalk .

Upon its creation New Jersey was among the most ethnically diverse regions in British North America, having not only a large Native American population, but also large Swedish and Dutch communities. Today New Jersey is still among the most ethnically diverse states, and all of those ethnicities live closer together than anywhere else. While New Jersey is the fourth smallest state, it has the 11th largest population. Also, according to 2000 census data the three most densely populated cities in the U.S. are all in New Jersey.

Old Jersey

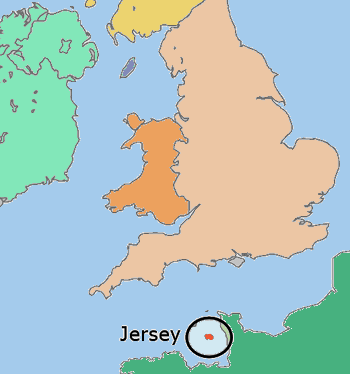

The island after which New Jersey is named is the largest of the Channel Islands between France and England, and is, in fact, the place where the Jersey dairy cow was originally domesticated. Closer to France, it was once part of the Duchy of Normandy, but to learn the history of its name we must go even further back.

The king in his charter called it “Nova Caesarea or New Jersey,” perpetuating a long-held but later strongly challenged belief that “Jersey” was simply a corruption of the word “Caesarea,” the Roman name for the island. “Caesarea” is an obvious tribute to Julius Caesar, under whose leadership the Romans conquered the island. Why this particular island should have been so honored is not entirely clear, especially given that there is no evidence that the Romans actually occupied Caesarea. They placed it on their maps and collected taxes from its inhabitants, but they built no structures or fortresses.

Some time in the fifth century A.D., the Franks moved south and west from Germany and defeated the Romans, driving them out of Gaul. Then, less than a century later, the Bretons (Anglo-Saxons who had taken over the British Isles from the Romans) moved into what is now northern France, and the region became known as Brittany . Jersey, now called Agna or Angia , was influenced by the takeover though not thoroughly consumed, retaining French as the native language.

Around 800 A.D. the Vikings began reeking havoc on the British Isles, France, and Brittany. Their origin was unclear to the Bretons—they knew only that they came from somewhere in the North Sea—but their raids each summer were brutal and widespread, burning villages, murdering people brutally and senselessly, and even plundering tombs looking for buried treasure. After a hundred years the Vikings, or Norsemen , had come to stay, and the King of France, Charles the Simple, purchased peace in 911 by surrendering to them modern northern France, the region historically known as Normandy (the Normans’ Land)2.

While not originally included in Normandy the island of Jersey was eventually won by the Norsemen, and its name bestowed by them. Whether they used a historical name—“Caesarae” which had been handed down since Roman times—or bestowed a new name from their own language is still debated.

There are two common theories about a possible derivation of the Viking word “Jersey.” One is the Old Frisian word “gers”, which means grass, combined with the common Viking suffix “-ey” meaning island. This would make Jersey “grassy island.” The other possibility is the proper Viking name “Geirr,” again coupled with “-ey,” which then became Geirr’s Ey, or Geirr’s Island.3

New Netherland/Sweden

New Jersey’s aforementioned ethnic diversity begins, of course, with the Indians. The Lenape, or Delaware as the English named them, inhabited the banks of the Delaware River upon the arrival of the first European explorers. A Lenape legend holds that when the Dutch arrived they asked only for enough land “for a garden spot,” thus conferring the state motto upon the region before states even existed. The legend continues that those Dutch eventually wanted more and more land, and in time the Lenape believed that they would “soon want all their country, which in the end proved true.”1

Actually the Dutch abandoned their attempt at settling the Delaware River, though they never relinquished their claim to the land, calling everything between the Delaware and Connecticut Rivers New Netherland . In 1624, to strengthen their defenses against the Indians and the English, they consolidated their colonists at Manhattan which had recently been “purchased” (see New York) by Dutch Governor Peter Minuit. Minuit, however, fell out of favor with his own government, and was recalled to Holland in 1631. In 1638 he sold his services to Queen Christina of Sweden, and led a group of Swedes to the Delaware River to find and purchase land from the Lenape to begin a colony. This one, New Sweden , thrived for almost two decades until the Dutch resolved to challenge the encroachment. In 1655 the Dutch captured New Sweden, once again bringing the area under the control of New Netherland.

Then came the English.

New York/Jersey

In 1664 King Charles II granted all the land that the Dutch were calling New Netherland to his brother James, Duke of York, and sent Colonel Richard Nicolls to claim it for him—by force if necessary. Force, alas, proved unnecessary when the Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant surrendered the entire colony (see New York), and Nicolls took over as the new Governor of what he, by prior authority of the Duke, named New York . Part of what Nicolls included in his domain was the region between the Delaware and Hudson Rivers, or modern New Jersey, but what Nicolls didn’t know is that while he had been at sea, sailing toward his showdown with Stuyvesant, the king had granted that part of New York to two friends, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, calling it Nova Caesarea .

Lord John Berkeley had been a financial advisor to Charles II during the years after his father’s execution while the English King lived in exile. Carteret had also been loyal to the King, sheltering him on his home island of Jersey for a time, and fighting valiantly albeit unsuccessfully, to save the island from the control of the Parliamentarians. Carteret’s family had for decades held much political control on the island. Sir George, following in his father’s Royalist footsteps, even hosted the eventual coronation of Charles II upon the death of Charles I.

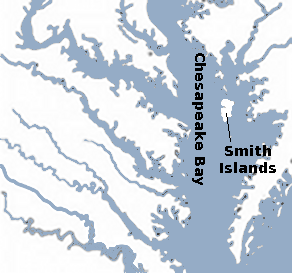

For his loyalty the now reinstated King Charles II gave Carteret a gift. He offered Sir George the Smith Islands off the coast of Virginia (now part of Maryland, they are a small group of islands at the southern end of Chesapeake Bay), and Carteret promptly renamed them “New Jersey”. His attempt at colonizing them failed, however, when the first ships he sent were captured by Parliamentary forces. Carteret never took possession of the islands.

In 1663 both Berkeley and Carteret were among the proprietors of the Carolina colony, and later both served on the Council on Foreign Plantations which advised the king to seize the Dutch colony of New Netherland. After acquiring the grant for New Jersey from King Charles they sent Carteret’s nephew Philip to govern their new estate, but he soon encountered resistance from colonists who had been granted estates by Richard Nicolls. Nicolls, of course, believed he was giving away New York property.

East/West Jersey

By the time the king settled the dispute between Nicolls and Carteret in 1674, Berkeley had given away his portion of New Jersey, now known as West New Jersey , to two Quakers, John Fenwick and Edward Byllynge, who immediately entered into a dispute over the property. The argument was arbitrated by none other than William Penn who, as payment for his services, took some of the disputed land and started his “social experiment” (see Pennsylvania) in West New Jersey.

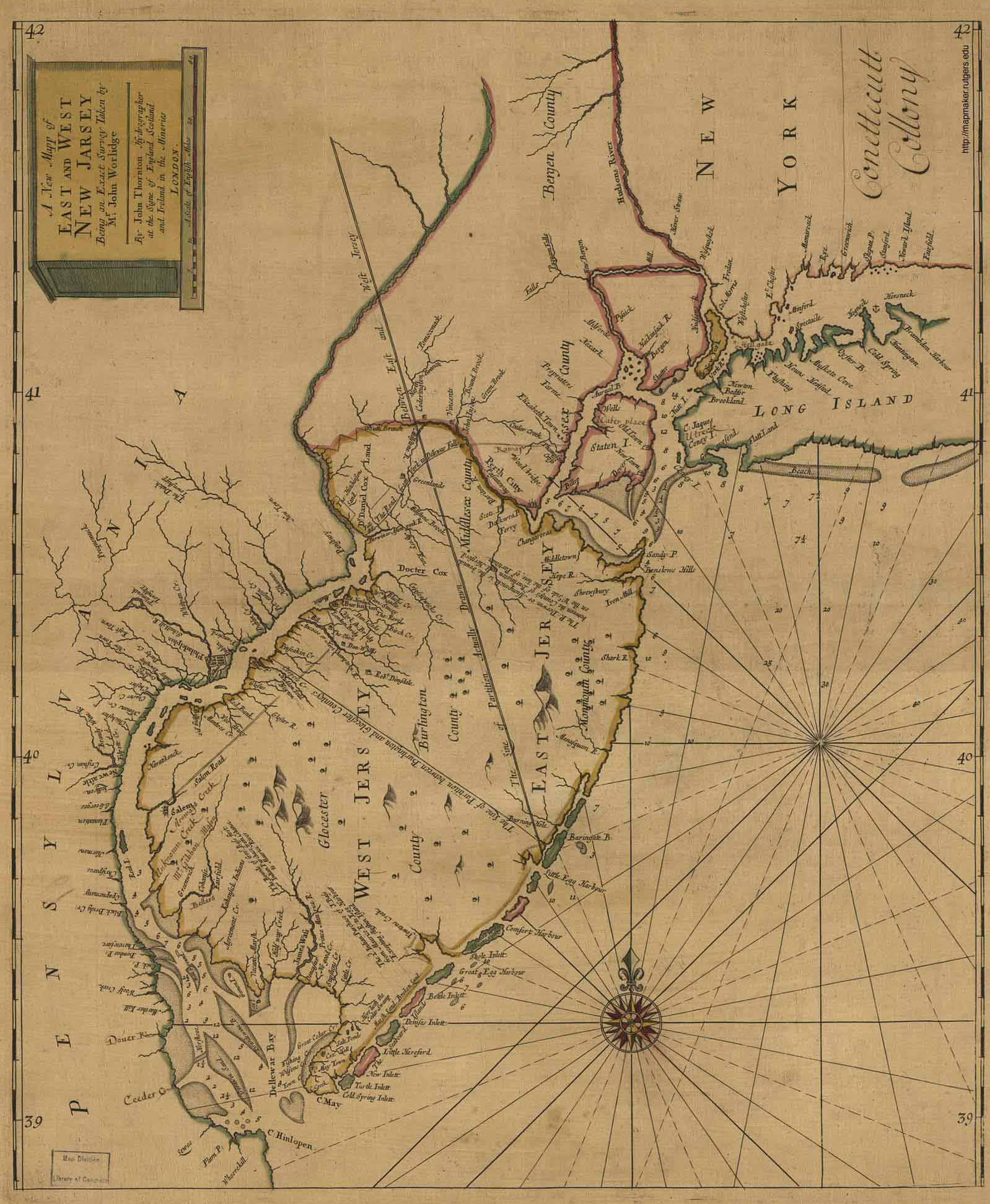

Though already owned in two separate pieces, on July 1, 1676 the colony was “officially” divided in two. The line between East and West New Jersey ran from Little Egg Harbor northwest to a point on the Delaware River just north of the Delaware Water Gap. Commonly in this time the “New” was dropped from the name, and the colonies were referred to as East Jersey and West Jersey .

In 1682 East Jersey was put up for public auction and sold to Penn and some of his associates for 3,400 English pounds, but governing the disparate population was troublesome to the proprietors, and in 1702 the crown reunited the colony, and took back control of it as a Royal Colony. Reunited, New Jersey was placed under the temporary governorship of Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury, Royal Governor of New York. Lord Cornbury is to this day considered one of the worst royal governors of any American colony. He is charged with having speculated on land while serving as governor and of plundering the public treasury for his personal benefit. This situation was naturally not acceptable to New Jersey, and the colonists clamored for more local control. The King responded, and in 1738 Lewis Morris of Monmouth County was named the first Governor of New Jersey.

Given the territorial dispositions of the Penn family over their colony at Pennsylvania and the similar ambitions of various enterprising governors of New York, it is somewhat surprising that New Jersey remained separate from either of those two colonies. It was, in fact, this proximity to New York and Pennsylvania that inspired Ben Franklin to refer to the state as “a valley of humility between two mountains of conceit.” In fact, largely because of its proximity to those two states, two New Jersey cities—Princeton and Trenton—hosted the U.S. Congress in 1784. Not only did New Jersey not get consumed by its powerful neighbors, it has the distinction of being the only state which retains to this day virtually the same borders defined in its original royal charter. On December 18, 1787, New Jersey solidified its autonomy, becoming the third state to ratify the Constitution of the United States.

End Notes

1. Green, Howard L., ed. Words that Make New Jersey History (New Brunswick, 1995), p. 6.

2. Balleine, G. R., A History of the Island of Jersey (London, 1950), p.27.

3. Balleine, p. 26.