NEW HAMPSHIRE

Live Free or Die!

—New Hampshire state motto

“For those of you who are feeling giddy or cocky or think this is all set, I just have two words for you: New Hampshire.”

—President Barack Obama,

during the 2008 presidential campaign,

reminding supporters of his loss to

Hillary Clinton in the

New Hampshire primary

Live Free or Die!

“Live Free or Die!” New Hampsherites proudly proclaim. Not “Live Free or Fight!” or even “Live Free or Write Your Congressperson!” No, in New Hampshire they don’t do anything half-way.

Among the areas in which New Hampshire can claim a unique superlative are

1. It holds the first primary—which is to say, before any other state—of every presidential election season.

2. It has the shortest oceanic coastline of any coastal U.S. state, running only about 18 miles along the Atlantic Ocean.

3. Mount Washington of the White Mountain Range, the tallest peak in the northeastern U.S. (which is a little like saying that your pinky is the largest finger on the far outside portion of your hand), claims the honor of having the “worst weather on earth.”

4. It was the first state to lose a native son in the American Revolution.

It was in Hanover, New Hampshire that the prolific, hilarious, and intrepid author, Bill Bryson, first spotted the Appalachian Trail and learned that it runs from Georgia to Maine. Having long been the adventurous type, Mr. Bryson set off to conquer this trail along with his old friend, Katz. From the effort, he produced the exquisitely entertaining book, “A Walk in the Woods.”

Our image in the 21st century of New Hampshire is one of colonial and revolutionary America. A place of gentle hills, quaint farms, and fiercely proud people who, despite being the 46th largest state in the country, are intent on making their voices heard in politics and in life. It is a tiny state that refuses to get “lost in the shuffle” as just another New England state. No, New Hampshire raises its hand and says that, “Our people are not afraid, not of being a little revolutionary, and not afraid to tell the nation who we choose to run for president of the country.”

It is truly the mouse that, every four years…roars.

Hampshire or Hampton?

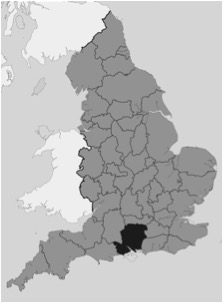

New Hampshire is named for the county of Hampshire—birthplace of Charles Dickens, home to JaneAusten, and custodian of the enigmatic Stonehenge—located on the southern coast of England. The word Hampshire comes from the Old English words “ham,” meaning home or village, and “shire” or “scire,” referring to an administrative district. One history of the English county of Hampshire written in 1909 asserts, however, that the name “Hampshire” is a misnomer, and that the official name of the county is and always has been “Southampton.”

“ ...there seems little doubt that the name is Saxon in origin—Ham-tun, the home-town or settlement, carrying us back to the...years during which the Saxon invaders...were making good their foothold...Ham-tun was the name they gave to their first secure base—Hampton it remained in popular style for at least one thousand years—and the name of the first permanent settlement thus became the name of the ‘hinterland’ which it dominated.”1

The Saxon “tun” was indeed a word indicating a farm or settlement and predates “shire,” which was a more formal administrative region. In 755 A.D. “Ham-tun scire” appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle—a sort of history of the world commissioned by King Alfred the Great of England in the late ninth century. Later the county began to grow and prosper, making it necessary to distinguish between the northern and southern portions. This produced “South Ham-tun shire,” and from there the word evolved into “Hampshire” to describe the whole county and “Southampton” which is the name of one of the largest cities in southern Hampshire.

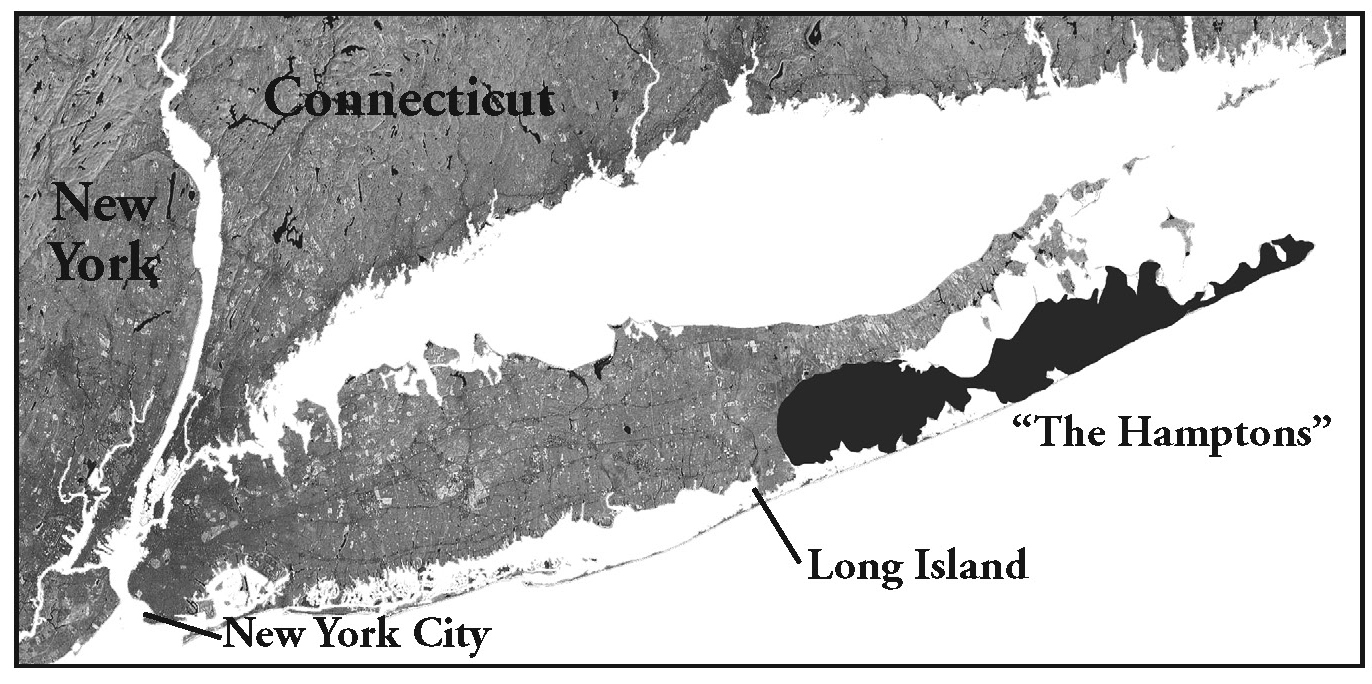

Hampshire or Hampton? The question is academic in England. But if you’re in the United States and you want to go to New Hampshire, you go to a state in New England; if you want to go to the “Hamptons,” you go to a group of villages on the eastern end of Long Island.

Captain John Mason

Captain John Mason, born 1585 at Kings Lynn in the county of Norfolk, England, is described many different ways in the various histories in which he is mentioned: pirate, one-time governor of Newfoundland, heroic naval captain, and successful London merchant. He was all of those things, as well as what he was most famous for: founder of New Hampshire.

By the age of twenty-five, John Mason had graduated from college, married, and bought himself a nifty little ship which he began using to capture legitimate trading vessels between Norway and Scotland. This was a lucrative business until he was caught in 1615 and forced to surrender his ship and thus his “career.”

It is stated with authority in some history books that Mason never saw the land which he would “found,” but this may not be true. In 1616, with a little help from his friends, he was appointed to the position of Governor of Newfoundland, a post he would hold for six years. During this time he made exploratory excursions westward into what would later become Nova Scotia, Maine, and possibly...New Hampshire.

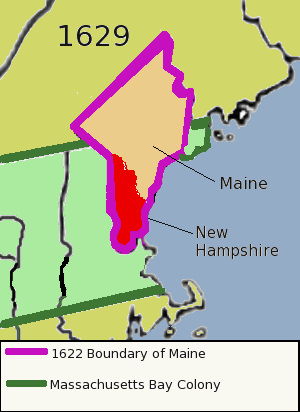

It was not until Mason returned to England however that he and his friend Ferdinando Gorges received a grant in 1622, made by the newly formed Council for New England on which Gorges served prominently. This new grant was for the “Province of Maine” between the Merrimack and Sagahadock (now the Kennebec) Rivers. Within a year, Mason and Gorges sent a man named David Thompson, his wife, and about ten indentured fishermen to establish a settlement and stake their claim. Thompson did exactly that and is a favorite son and source of much pride for the state of New Hampshire. He built a stone manor which he called Pannaway at the mouth of the Piscataqua River, a region Thompson named “Little Harbor” (now the town of Rye). The manor stood for some sixty years and began what would be the third permanent English settlement in the New World after Jamestown and Plymouth.

Back in England, Mason had settled in Portsmouth, Hampshire and established himself as a successful businessman, though he complained in his letters that his colonizing efforts had yet to bring in any money. On the 7th of November in 1629, Gorges and Mason divided their grant amicably: Gorges took Maine north of the Piscataqua, and Mason took the rest and named it “New Hampshire”.

Some New Hampshire historians bother to provide a motivation for this name: “It was the home of his family’s estate,” “he spent many years there as a child,” etc. These reasons generally ignore the fact that Mason was born and raised in the county of Norfolk on an estate which had been in his family for several generations, his mother was from Yorkshire, and he did not move to Portsmouth in Hampshire until adulthood. The only available biography of Captain John Mason gives a more plausible, if not very exciting reason: “...and Mason called it New Hampshire, out of regard to the favor in which he held Hampshire in England, where he had resided many years.”2

Laconia and Masonia

Attempting to follow the grants and patents distributed by theCouncil for New England is a frustrating endeavor. As described by one historian, the Council

“...gave what they never owned, set bounds to that which had never been seen, fixed lines that had never been surveyed and laid the foundation for countless quarrels and much trouble in future years.”3

Cases in point: Laconia and Masonia.

Shortly after dividing their original grant, Mason and Gorges formed the Laconia Company and applied for a new grant west of (and in fact, overlapping) Mason’s New Hampshire. They called the land “Laconia” as it was in the lake region, and also in hopes of finding the fabled “Lake of the Iroquois” and subsequently taking over the fur trade in New England. The endeavor proved impossible because the lake they sought did not exist, however the effort did spawn new settlement along the Piscataqua River.4 The Laconia Company went bankrupt, but Mason retained proprietorship of some of the land in the Laconia grant.

In 1635 the Council for New England surrendered its charter, and the responsibility for granting land and patents reverted to the king. Mason quickly had his New Hampshire grant confirmed to him and in the same document was given ten thousand acres in what is now Maine which was called “Masonia”. Historically speaking Masonia was quickly absorbed into Maine and forgotten, but the document granting the land had the confusing title “Grant of the Province of New Hampshire to Mr. Mason, 22 April 1635, By the Name of Masonia.”

John Mason died later that year, leaving his many patents and land grants to his heirs. Years later his eldest grandson would go to New Hampshire to pursue his legal rights to the land.

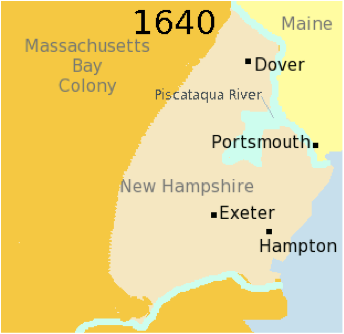

The Four Towns

By 1640 there were four main “plantations” or towns in the region of the Mason grant. Little Harbor, which was founded by David Thompson and expanded three miles up the Piscataqua River, would later assume the name Strawberry Bank, and still later the name Portsmouth. It was joined by Northam—later Dover—a town begun by the Hilton brothers, also under the direction of the Laconia Company. The other two towns were born out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. One was Exeter, founded by John Wheelwright, who had been expelled from the MBC for heresy and sedition and moved north to found his own settlement. The other was a town settled under the auspices of the MBC at a place the natives called Winnacunnet and which the colonists named Hampton.

These four towns were bound to each other only by their relative proximity and by their tenuous, and perhaps a bit self-conscious, separateness from the imposing Massachusetts Bay Colony. One New Hampshire historian writes,

“In 1640 the term “New Hampshire” had little or no meaning for the inhabitants of the four plantations. Many probably knew that Captain John Mason had used the name to identify territory included in one of his many patents, but few cared about the legal status of that or other patents granted by the Council for New England. The Council no longer existed, Mason had died, and crown officials were so busy trying to resolve England’s internal problems that imposition of effective royal authority in New England seemed unlikely.”5

In fact by the autumn of 1642 all four towns had applied to Massachusetts for inclusion in its government and were accepted as part of the Bay Colony. Mason’s heirs, in particular his grandson Robert Mason, had no chance to claim his inheritance during the English Civil War and the reign of the Puritan government of Oliver Cromwell, but after the restoration of the throne to Charles II in 1660, he petitioned the King for redress. At first nothing was done, but Mason persevered, and in 1679 King Charles II declared New Hampshire a Royal Province—separate from Massachusetts—under Mason’s proprietorship, meaning he now owned all unsettled land from the original grant and could collect rent from the current landholders. The colony of “New Hampshire” was now firmly planted.

Massachusetts Again

Well, maybe not. Opposition to royal rule and to Mason’s proprietorship was strong. Two different governors attempted to enforce English laws pertaining to land tenure and customs, in particular the hated “Navigation Acts” which were intended to force all trade between English colonies to go through England on English vessels so that duties could be collected. The acts were summarily ignored in New England, and no amount of intimidation by New Hampshire’s governors could force compliance. Mason, too, was frustrated in his attempts to collect rents or to gain control of unsettled lands. As a final insult, he was even physically assaulted at the peak of tensions in the colony.

In 1685 a different kind of unrest swept the colony. Those who wished a return to government by Massachusetts had their hopes dashed when that colony’s charter was revoked, and the “Dominion of New England” was established—the king’s attempt to erase the carefully drawn boundaries and combine all the New England colonies into one carefully managed unit. At this point, confusion ruled among the northern colonies who didn’t know if their provincial status existed. To make matters worse, the appointed governor of the Dominion was Edmund Andros, a tyrant who made enemies wherever he governed.

Fortunately the Dominion was short-lived, ending with the Glorious Revolution which brought William of Orange and his wife Mary to the throne of England in 1688. Massachusetts now reverted to its pre-Dominion government, but New Hampshire was totally without authority. Even the Mason proprietorship was deprived of its driving force, as Robert Mason died that same year. At this point the four towns came close to establishing their own self-devised, self-imposed government but the Puritans in Hampton feared too much secular control, and the attempt failed. The only solution now available was the reannexation to Massachusetts, and this was done rather efficiently by March of 1690. Once again, New Hampshire ceased to exist.

New Hampshire, at Last

Still, the years of royal government had convinced more and more New Hampshire residents that the colony had an independent destiny separate from that of Massachusetts. The beginning of the eighteenth century brought a sense of optimism for the future of what one official called “little New Hampshire,” making separation and self-government a real prospect.

In 1699 New Hampshire petitioned the English authorities to separate it from Massachusetts, while at the same time Massachusetts lobbied for complete control over both. Instead of deciding for either colony, a compromise was instituted whereby the colonies would remain separate but would have the same governor. This solution was surprisingly agreeable to most people, but the tensions between the colonies would ebb and flow for the next forty years.

Finally, in 1741, after a lengthy dispute over the location of the border between Massachusetts and New Hampshire, a border which was unnecessary when the two colonies were governed as one, the English Privy Council handed down a quite favorable ruling for New Hampshire, placing its border south of not only Massachusetts’ claim but of New Hampshire’s claim as well.

The Proprietorship

In the meantime, the legacy of Captain John Mason continued to turn up like a bad penny for decades. Around 1690 Robert Mason’s sons sold the proprietorship to Samuel Allen, an energetic London merchant who had begun to invest heavily in New Hampshire. Allen succeeded in having himself appointed governor of the colony but was frustrated, as Robert Mason had been before him, in his attempts to collect payment or rents from the colonists.

In 1705 a group of representatives from the New Hampshire towns put together an offer to effectively buy out Allen, and Allen probably would have accepted, had he not died on the day after the proposal was made. This morbid but fortuitous turn of events prompted Cotton Mather to remark,

“I cannot but admire at the providence of Heaven, which has all along strangely interposed, with most admirable dispensations, especially with strange mortalities , to stop the proceedings of the controversy about Mason’s claim just in the most critical moment of it.”6 (emphasis added)

In the 1730s the proprietorship reared its ugly head one last time when John Tufton Mason, a descendant of the Captain, appeared in Boston to stake his claim to New Hampshire. Tufton eventually sold his rights to a group of Portsmouth businessmen who are remembered today as the “Masonian Proprietors.” For nearly forty years these proprietors set land policy and granted townships judiciously without attempting to profit unfairly from their powers, and thus the problem of the proprietorship was solved for good.

Statehood and the Western Border

In 1763, with the Treaty of Paris that ended theFrench and Indian War, the territory west of the Connecticut River was deeded from France to England and was claimed by both New York and New Hampshire. Quickly, however, the residents of the disputed land declared their independence from either colony. In 1777 Vermont’s sovereignty was recognized by both claimants, and the borders of New Hampshire were now fixed.

On June 21, 1788 New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution. With New Hampshire, two thirds of the states had now ratified, causing the Constitution to take effect and thereby giving that state yet another source of historical pride.

End Notes

1. Varley, Telford and Wilfrid Ball, Hampshire (London: Adam & Charles Black, 1909), p. 3.

2. Dean, John Ward, Capt. John Mason: The Founder of New Hampshire , (New York, 1887), p. 21.

3. Hadley, George Plummer, History of the Town of Goffstown 1733-1920 , (Concord, 1922), http://www.usgennet.org/usa/nh/county/hillsborough/goffstown/book/chap3.html, created June 28, 2000, accessed July 23, 2009.

4. Daniel, Jere R., Colonial New Hampshire, A History , (Millwood, 1981), p. 24.

5. Daniel, p. 38.

6. Daniel, p. 129.