NEVADA

“Viva Las Vegas!”

—Elvis Presley, Viva! Las Vegas!

Danny: “You’re either in, or you’re out. Right now.”

Linus: “Las Vegas, huh?

Danny: “

America’s Playground

.”

—From Ocean’s Eleven (2001)

Casinos

The irony is lost on no one—the state with legalized gambling and prostitution, right next door to the one which comes closest to having a state-sanctioned religion. To many, Nevada is an adult Disneyland; for others, it is a waste of space, time, and human energy; and for still others, it is a place of sin and corruption to be avoided and/or converted. People who have never been there may imagine Nicolas Cage and Elizabeth Shue leading their desperate, pathetic lives in 1995’s Leaving Las Vegas , or the “Flying Elvises” in yet another Nicolas Cage movie, Honeymoon in Vegas , or perhaps any version of Ocean’s Eleven . Nevada’s largest city does not want for TV and movie exposure.

Big (monstrous?), lavish (wasteful?), shimmering (gaudy?) casinos with lights bright enough to be seen from outer space—that’s Las Vegas. And the rest of Nevada? It’s a huge desert with a bunch of smaller Las Vegases dotting the landscape, tiny-to-medium-sized towns that you can always see from miles away because of the massive lighted signs guiding the way to the casinos. Drive into the state at night on virtually any highway, and the border is unmistakable.

It was in 1931 when Nevada officially legalized gambling, partly in anticipation of a growth in tourism with the construction of the Hoover (Boulder) Dam. In its infancy the industry was financed by—and intimately connected with—organized crime, prompting many other states not to follow Nevada’s lead. Eventually however, the industry was cleaned up and legitimized and proved to be the tourism magnet that the state had hoped for.

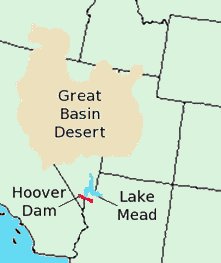

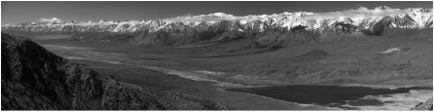

Nevada imparts other images, too. While it is comprised mostly of the Great Basin of the American West, Nevada’s natural beauty takes the form of breathtaking plateaus and scenic deserts, and the ominous Hoover Dam and corresponding Lake Mead rival Las Vegas in their inspiration of wonder at man-made monstrosities. There are those who associate Nevada with marriage and divorce, and the ease with which one can come by either within her borders. Still others associate Nevada with nuclear testing and the disposal of radioactive waste. And then there are those who connect the entire state with a sixty-square-mile military aircraft testing facility known as “Area 51,” which some believe is the U.S. government’s site of choice for examining UFO’s and space aliens.

Columbus

In 1848 the state we call Nevada was among the spoils claimed by the U.S. after the Mexican-American War. Often referred to as “Eastern California,” the region was also commonly referred to on maps as the “Great American Desert” (a term perhaps more commonly associated with the continent’s central plains), “Great Basin,” and sometimes the “Fremont Basin,” after John C. Fremont, who explored and mapped much of the American West for the U.S. government. This massive desert east of California and west of Salt Lake City, was seen as an obstacle to be overcome for fifteen years as prospectors and pioneers crossed its brutal sands on their way to California.

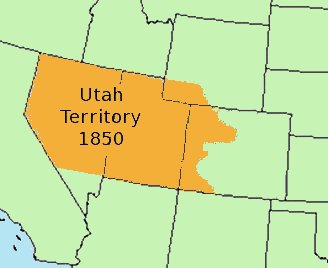

The exception, of course, was the Mormons. They had, since 1847, been settling the Great Salt Lake region of Utah, and for much of that time, lobbying Congress for territorial status, first for their own provisional state of Deseret , but eventually for whatever form the federal government deemed appropriate. Utah Territory was created in 1850 and included all of current Nevada except for the southern tip. In 1851 a group of Mormons led by John Reese and Steven A. Kinsey established Mormon Station , a trading post near the California border intended to service travelers as they attempted to cross the Sierra Nevada mountain range. By fall of the same year, several other settlers joined Reese and Kinsey, and the population grew to perhaps a hundred residents, both Mormon and Gentile. The first attempt to form a territorial government for the region was born out of the “squatter meetings” held by these industrious residents. By the end of 1851 they had drafted a petition to Congress to form a separate territorial government for western Utah, but the petition was never delivered, and the Utah government in Salt Lake City began to take measures to establish law and order in the region. The oldest permanent settlement in Nevada, Mormon Station, was made the county seat of Carson County in 1854 and renamed Genoa (Jah-NO-ah) in 1856.

Throughout the 1850s there was a sort of tug-of-war between California and Utah regarding the Carson Valley region. Many of the settlers in the valley were miners who felt they had more in common with the residents of California than with those of their own designated territory. In 1853 and again in 1855, some of these residents petitioned California for annexation, and each time the Utah territorial legislature took measures to assert more control over the region.

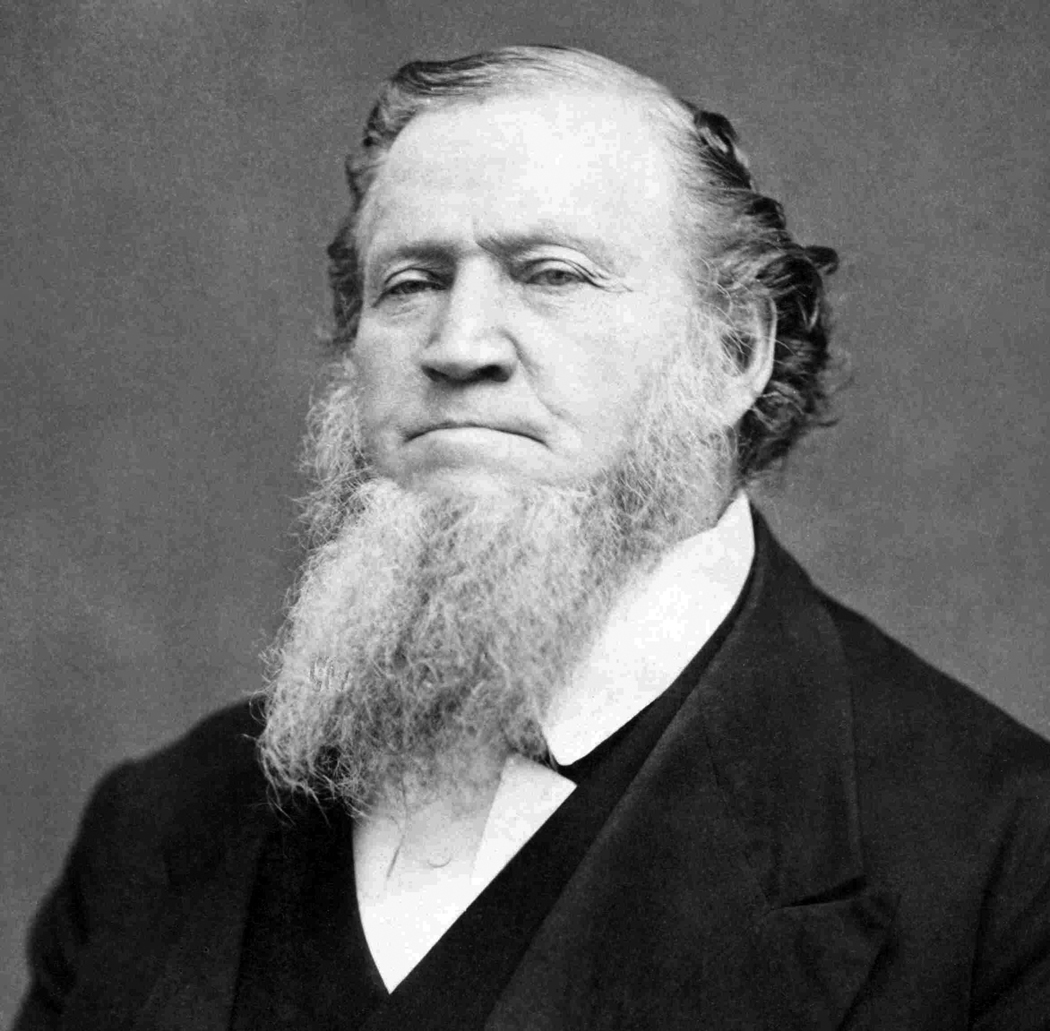

In 1857 most of the Mormon settlers in western Utah Territory made a dramatic exodus and returned to Salt Lake City. Heeding a call from Brigham Young, who was preparing to wage the “Mormon War” against government troops, they were told to “bring as much ammunition as possible and to hurry.”1 The Mormons attempted to govern the Carson Valley remotely, but the void of local authorities spurred the next attempt at separation from Utah. On August 3, 1857, a meeting of the remaining residents selected a delegate to present to the U.S. Congress a memorial which requested territorial status separate from that of Utah. The name the squatters chose for their territory was Columbus, and the capital was to be Genoa.2

Some in Congress saw the petition as an opportunity to “compress the limits of the Mormons” and reported on it favorably. James M. Crane, the delegate chosen by Carson Valley residents to deliver the petition to Congress, wrote a letter in February of 1858 suggesting that territorial status was imminent but in an off-hand comment noted that the name for the new territory had been changed to “Sierra Nevada.” Meanwhile tensions had eased a little between the federal government and Salt Lake City, and the distraction of the impending Civil War caused the petition to be tabled.

Silver and Gold

The Comstock Lode of 1859 proved to be the impetus for a great migration into the region (as well as an attractive theme for casinos a hundred years later). Most of the new population came not from the east but from the California gold fields to the west. These were seasoned miners accustomed to mining town politics and society. By the spring and summer of 1860 thousands of miners were pouring into the area just north of Genoa to take part in the biggest silver strike in world history. Carson City , formerly a small trading post named Eagle Station , became the new center of government and trade.

In an attempt to establish law and order, the Gold Hill Mining District was created in June 1859, but it proved too weak to manage the throngs of new residents. Miners were well acquainted with the mechanics of territory creation, and because they were genuinely dissatisfied with Mormon control, they took every opportunity to press for separation from Utah. In 1861 officials in Salt Lake City recognized the miners’ goal and made a last ditch effort to govern the region effectively, providing for the incorporation of Virginia City and moving the county seat from Genoa to Carson City. But it was too little, too late.

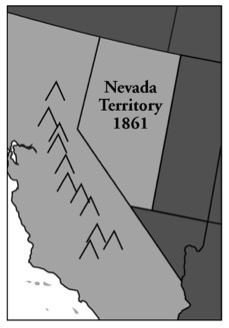

Back in the eastern states, the Civil War had been brewing and by 1861 had begun in earnest. With the departure of the southern states from the U.S. legislature, a major obstacle to territory creation was removed, as the slavery issue was now moot. While it is true that Carson Valley residents had wanted separation from Utah for a number of years, it is also fair to say that once the petition was re-submitted on February 26, 1862, it moved through successfully at lightning speed. On March 2, after passing the House, a companion bill passed the Senate and President Buchanan signed it that very day.

A Snow-Covered State?

It is not clear exactly who inserted the name “Nevada” into the bill creating the territory in 1861. The document was written by Missouri Senator James S. Green but chances are he used the name, or half of the name Sierra Nevada , which had been proposed four years earlier for the same region. There was already a Nevada City in California, and it was among the oldest mining towns in that state. In fact, some of the miners who had rushed to the Carson Valley after the discovery of theComstock Lode in 1859 had moved there from Nevada City.

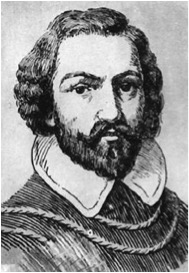

There is no argument, however, that the name was inspired by the Sierra Nevada, the mountain range that runs along the eastern border of California. The word sierra is Spanish for “saw-toothed mountain range,” and nevada , also Spanish, means “snowy,” “snow-covered,” or “snow-fall.” Juan Rodríquez Cabrillo, a Portuguese navigator who explored the coast of California in 1542 while sailing for Spain, named the snow-covered mountains which he could see far inland Sierra Nevada . Later Spanish explorers wrote of these mountains but not until 1776 did a Franciscan missionary named Pedro Font place “Sierra Nevada” on a map though, as one historian explains, he intended the name to be “descriptive, not specific.”3

Nevertheless, Sierra Nevada became the permanent appellation, and since the first English-speaking Americans began arriving in California the name, according to Guy Rocha, writing for the Nevada State Library and Archives Department of Cultural Affairs, has been misunderstood and mispronounced. Rocha complains of naive attempts to make the words plural, and explains that “Sierra” defines a range of mountains and so is already plural, and that “Nevada” is merely descriptive. “Sierra Nevada Mountains,” he continues, is redundant while “Sierra Nevadas” is simply grammatically incorrect.

Rocha also points out one of the great ironies in the choice of names for the new territory: the Sierra Nevada is in California. While the original petition for the creation of Nevada Territory requested a western border along the crest of that mountain range, it was fairly certain that California, which was already a state, would never approve of such a drastic change in her own borders, a change that would decrease her size dramatically and potentially remove rich mineral deposits. The other great irony in the name “Nevada” is that it means “snowy” or “snow-covered,” and yet it describes what was acknowledged, even in the 1850s, as the “Great American Desert.” Of all of the striking images we may have of Nevada, snow-covered is rarely one of them.

The Telegram

Two days after Buchanan signed the territory of Nevada into existence, Abraham Lincoln was sworn into office as the new U.S. president. He proceeded to appoint all of the administrators for the new territory and among them, in the post of Territorial Secretary, was one Orion Clemens, who moved out west to assume his new position accompanied by his younger, and soon to be much more famous, brother Samuel—a.k.a. Mark Twain.

The issue of the name and the borders for this fledgling territory were not yet completely decided. In 1862 the second territorial legislature adopted a new name, Washoe . The Washoe Indians were native to the Carson Valley and Lake Tahoe regions, and while the vague reference “Washoe Country” had been used occasionally to refer to western Utah after the Comstock discovery, no counties were ever officially labeled with that name. Now it was being proposed for the whole territory.

At the first constitutional convention in November of 1863, the issue of a name was debated. The act calling for the convention had already renamed the potential new state Washoe , but many at the meeting were dissatisfied with the change. Other names were proposed, including Humboldt and Esmaralda , but in the end, the state fathers agreed on the original name of “Nevada.” The second constitutional convention was held in March of 1864, and after what one historian calls a “warm debate,” the name Nevada was decided on once and for all.

In the meantime, Nevada’s borders were already changing. Originally her eastern border was set at 116 degrees west longitude, leaving out about a third of the state’s modern-day area. Her southern border initially went only as far south as the northern border of Arizona. Gradually, these borders were moved. Twice, while Nevada was still a territory, her eastern boundary was moved eastward. Then, after statehood, another sliver of Utah was given over to Nevada, and the southern section of the state, below the line of 37° north latitude, was also added.

In March of 1864, Congress passed the enabling act for Nevada, and the state legislature set about finalizing their constitution. So as not to waste any time, the entire document was wired to Abraham Lincoln at a cost of $3,416.77 making it the longest telegram ever dispatched to that time. President Lincoln approved it, and the State of Nevada came into existence on October 31, 1864.

End Notes

1. Elliott, Russell R., History of Nevada (Lincoln, 1973), p. 56.

2. Elliott, p. 58.

3. Farquhar, Francis P., History of the Sierra Nevada (Berkeley, 1965), p. 16.