NEBRASKA

“From the town of Lincoln, Nebraska

with a sawed-off .410 on my lap”

—Bruce Springsteen, Nebraska

“Ready or Not, Omaha, Nebraska…”

— Bowling for Soup,

(Ready Or Not) Omaha, Nebraska

“Go Big Red!”

Nebraska’s reputation is a bit enigmatic. Some people think of grazing cattle or a Big Mac, as Nebraska has a thriving beef industry. But when it comes to instant images, more of us probably associate beef with Texas or Montana. Corn comes to mind, but its association with that crop cannot rival that of its eastern neighbor, Iowa. Perhaps if Kevin Costner were to make a movie about a corn field in Nebraska....

It separates the fertile farm land of the Midwest from the Rocky Mountain states of Wyoming and Colorado. It sits between the rolling plains of Kansas and the badlands of South Dakota. Nebraska’s reputation draws on all of these neighbors to form images of a northernish Great Plains farming state in the heartland of the country.

If Nebraska has a personality of its own, it must surely be associated with football. The whole state lives for football season—at least it seems that way. Consider...

•The nickname “Cornhusker” was not adopted by the University of Nebraska as its mascot because of some previous association with the state. It was, in fact, a name that the state adopted from the University football team (and other athletic teams) in 1945.

•According to the Nebraska Blue Book , the official state song, A Place Like Nebraska , contains the line “with cool winding streams / and good football teams...”

•The first University of Nebraska football game was played in 1890—only twenty-three years after Nebraska became a state.

With its short, wide panhandle and its curved northeastern corner, Nebraska’s shape on the U.S. map is distinctive, breaking up the monotony of all the pseudo-rectangles that surround it. Historically, both the Mormon Trail and the Oregon Trail passed through Nebraska, as it is a convenient state to cross. As one Nebraska history book calls it, “A place on the way to somewhere else.”1

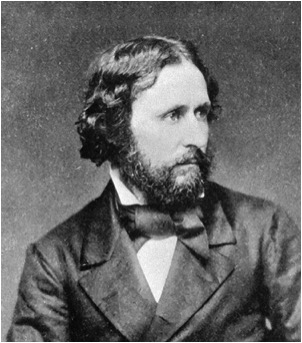

Fremont

John C. Fremont, the “Pathfinder” of the American West, is often credited with “naming” Nebraska. This reputation is due to a note made in his report on his very first expedition westward in 1842. He wrote,

“Crossing on the way several Pawnee roads to the Arkansas, we reached, in about twenty-one miles from our halt on the Blue, what is called the coast of the Nebraska, or Platte river.”2

This sentence would indicate that the name for what we now call the Platte River was not firmly settled in 1842, but despite this particular comment, Fremont refers to the river as the Platte in every other reference in the report. Indeed, the exhaustingly long title of the document is “A Report on an Exploration of the Country Lying Between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, on the Line of the Kansas and Great Platte Rivers .” (emphasis added)

John C. Fremont

Why Fremont chose to be ambiguous about the river’s name in this particular reference is not clear, but his maps of this expedition also use the uncertain label “Nebraska or Platte River.” Apparently by the time his journal was transcribed and published, the name Platte had been more firmly decided upon.

Whatever the reason, his ambiguity had some effect. In 1844 an expansionist named William Wilkins, serving at the time as U.S. Secretary of War, submitted his annual report to President Zachary Taylor. It contained the recommendation that the region west of the Missouri River be organized into a territory and that “The Platte or Nebraska River being the central stream would very properly furnish a name to the territory. Troops and supplies from the projected Nebraska territory would be able to contend for Oregon with any force coming from the sea.3” Wilkins’ naming suggestion was by no means revolutionary. Three of the four territories—Iowa, Missouri and Arkansas—which had so far been created out of lands obtained in the Louisiana Purchase had been given the aboriginal names of major rivers in their regions, rivers that had originally been named after tribes who lived nearby. While the continent’s central plains are not generally known for their dominant rivers, the system seemed to be working and so government officials like Wilkins were disposed to continue it.

The French

But John C. Fremont was not the first to use the name Nebraska. Nor did he apply the name Platte. He was using names which had been previously documented by French explorers more than a hundred years earlier.

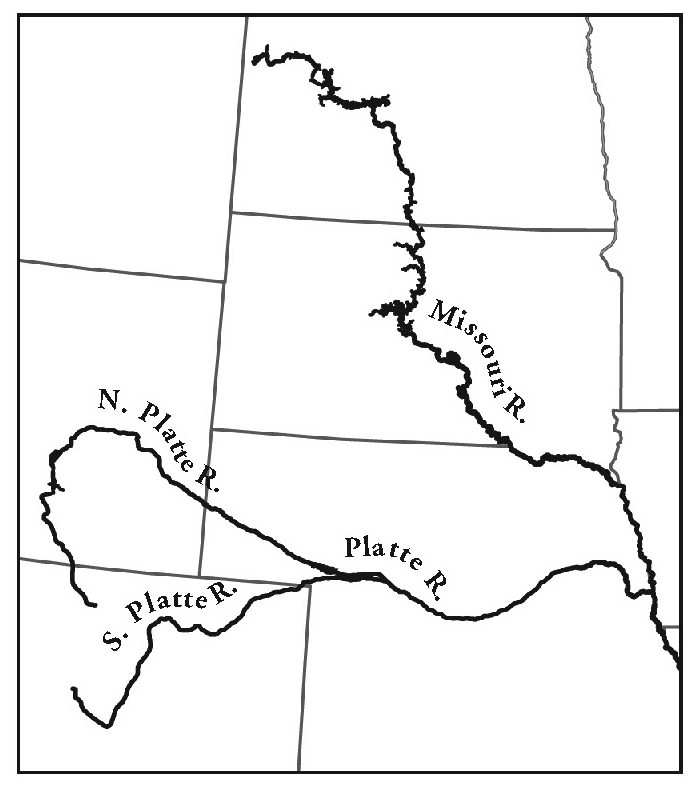

Ètienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, is generally regarded as the first white man to explore the Platte River. He did so in 1714, and noted in his journal, “Higher up the river, one finds the Large river, called Nibraskier by the French and Indians.”4

But Bourgmont may have been a bit premature. For twenty-five years after his trip, the French explored very little west of the Missouri. Then in 1739 two Canadian Frenchmen, brothers Pierre and Paul Mallet, proposed finding a route to the Spanish settlements in New Mexico by way of the Missouri River. In their attempt, they found and named the Platte River. Chances are they knew of Bourgmont’s “Nibraskier” River, but given their circuitous wanderings (they started in New Orleans!), they did not realize that the river they named "Platte" was the same as Bourgmont’s "Nibraskier."

Or perhaps they did. The words actually mean the same thing. Platte is French for “flat,” while Nebraska or Ni-ubthatka is an Oto (Siouan dialect) word for “flat, or spreading river.” Bourgmont, who had lived among the Missouri Indians for many years and was married to a Missouri woman, would have been accustomed to using the native names for the rivers he found. The Mallets, whose motivations were to find and plunder the Spanish silver mines that they believed existed in New Mexico, would have been more likely to translate the word, using a French name rather than that of the natives. At any rate, the Mallet’s name for the river became common on French maps, and by the time of Fremont’s 1842 expedition, Platte was the most widely used name for Nebraska’s dominating river.

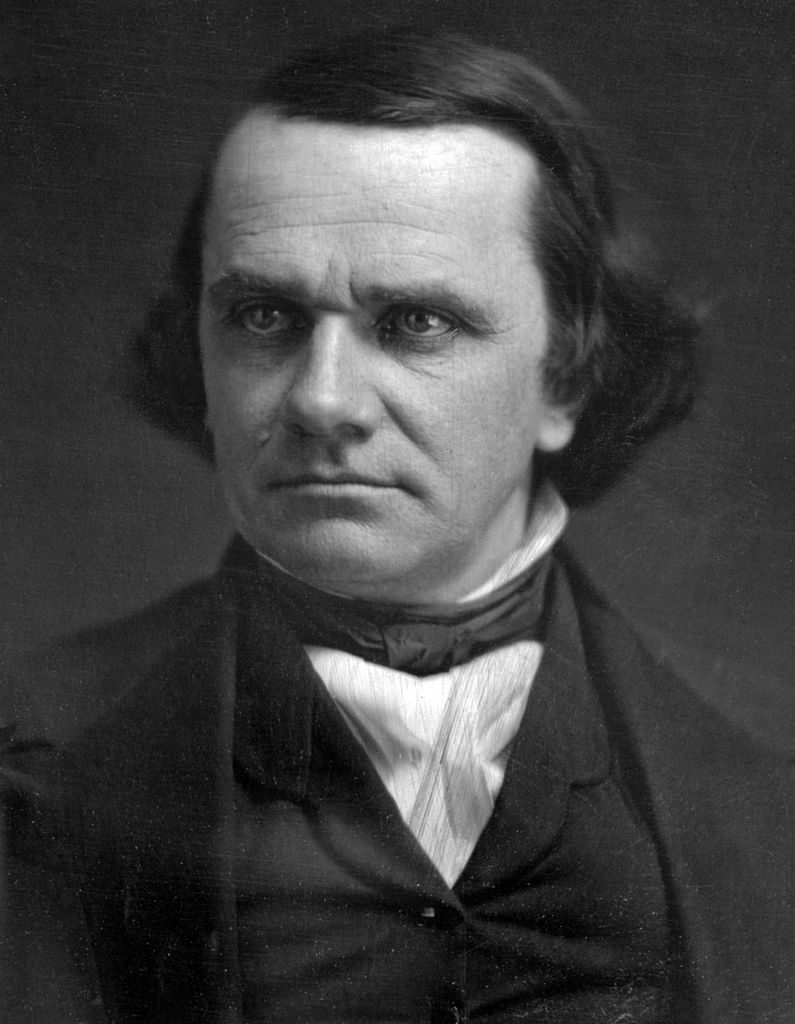

Stephen Douglas

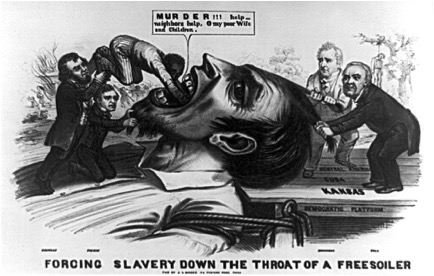

William Wilkins’ suggestion in 1844 to create a new “Nebraska Territory” seemed to make an impression. On December 17, 1844, a bill was introduced in Congress to do just that. The proposed territory included what are now Nebraska, Kansas, the Dakotas, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming and Montana. But unfortunately for Wilkins and other champions of organizing the region, the divisions between north and south, free and slave, were once again affecting territorial politics. The "Missouri Compromise" had dictated that no slavery would be allowed north of the 36º 30’ parallel, and the South, wanting to keep the balance of power in the Senate, would not approve any bill that created a new free state.

For the next ten years, various forces would clamor for territorial organization of Nebraska. The most vocal were the railroad companies who wanted to build a line along the Platte River. But also demanding territorial status were settlers—those who wanted to move into the region, as well as those who were already squatting there in defiance of the law.

It was the railroad issue that most motivated Stephen Douglas. Representing Illinois in the U.S. Senate, he was interested in establishing Chicago as a railroad hub, and to this effect lobbied hard to get the Platte River route built. It was Douglas who had introduced the first Nebraska Bill in 1844, and he would continue fighting for the territory for ten years.

Finally, in 1854, all of the issues came to a head. The solution involved dividing the territory and repealing the Missouri Compromise. Douglas and the Republicans agreed to cut off a southern section of what would have been Nebraska and call it “Kansas,” thereby creating a territory that southerners were sure they could bring into the southern (i.e. slavery) fold. The bill is the historically significant Kansas-Nebraska Act, though in some Nebraska history books, it is referred to, with perhaps a tinge of contempt or hubris, as the “Nebraska-Kansas Act.”

If Nebraska’s fortunes seem historically to be tied to those of its neighbors, nowhere is that more apparent than in the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. It was the creation of Kansas that allowed the creation of Nebraska, and it was Kansas that became the boiling pot that sadly foretold the coming Civil War.

In a final insult (if one is passionate about such things), Kansas was granted statehood in 1861, but Nebraska’s would not come until six years later. In the meantime, Colorado and the Dakota Territories were created in 1861 and Idaho Territory two years later (in its original form which included current Montana and Wyoming). Now Nebraska had the borders which define it today, and statehood was becoming imminent. But there was one more hurdle to cross.

The final leg on the march to inclusion as a state was to be unique for Nebraska. It is the only state created since Ohio that was granted statehood without the signature of the sitting president. Andrew Johnson’s ostensible reason for vetoing the 1867 statehood proposal was that the state’s constitution did not allow suffrage to non-white citizens. This was baloney, of course, because Andrew Johnson was a latent racist. He had been a slave-owner before his political career, and fought during his entire presidency against the 1866 Civil Rights Act and against ratification of the fourteenth amendment, which guaranteed the right to vote to all men regardless of race. His conciliatory overtures to the south after the Civil War made him reviled by the Republicans in Congress, leading to his eventual impeachment. Johnson’s real motivation was that Nebraska would be dominantly Republican, and its statehood would provide two more Republican senators to the U.S. Congress, along with three more electoral votes in his looming re-election bid.

Congress, too, was concerned—probably more genuinely so—about the flaw in Nebraska’s constitution, so it created a provision in the eventual bill that would only grant statehood if the problem were remedied—that is, if Nebraska guaranteed the right to vote to non-white Americans. The veto issued by President Johnson was of the “pocket” variety – that is, he allowed ten days to pass after the bill reached his desk without signing it. Curiously, a similar set of circumstances was being played out at the same time with regard to Colorado. Johnson received enabling bills for both territories on the same day, but his veto of the Colorado bill was of the traditional variety. Still more curiously, while Congress overrode the veto of the Nebraska statehood bill, on the very same day they did not override the veto of the Colorado enabling act.

Thus, Nebraska became a state nine years before its neighbor to the southwest on March 1, 1867, and without the signature of the U.S. President. The football rivalry between the two states would just have to wait.

End Notes

1. Luebke, Frederick C., Nebraska: An Illustrated History (Lincoln, 1995), p. 7.

2. Fremont, J. C., The Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains, Oregon and California (Buffalo, 1851), p. 17.

3. Sheldon, Addison Erwin, History and Stories of Nebraska (Chicago, 1913), p. 232.

4. James C. Olson and Ronald C. Naugle, History of Nebraska (Lincoln, 1997), p. 31.