MONTANA

Like many fly fisherman in western Montana where the summer days are almost Arctic in length, I often do not start fishing until the cool of the evening. Then in the Arctic half-light of the canyon, all existence fades to a being with my soul and memories are the sounds of the Big Blackfoot River and a four-count rhythm and the hope that a fish will rise. Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it.

— A River Runs Through It (1992)

“Nobody’s Perfect

I gotta work it…”

—Miley Cirus, aka Hanna Montana,

Nobody’s Perfect

Anthony ‘Tony’ Soprano Sr.: [about his father] He’d been in prison. He was away when I was a little kid. They told me he was in Montana, being a cowboy.

—from The Sopranos

The Great Outdoors

Montana is that huge northwestern state that looks like it took a bite out of Idaho. It is a place that, without knowing much about it, people think of as beautiful and inviting. Remember that line in the movie Hunt for Red October where Sam Neill says weakly, as he lay dying in the arms of Sean Connery, “I would like to have seen Montana.” Most of us have never been to Montana, but it seems like the place you go when you want to disappear into the unspoiled nature of its shining western mountains or the vast rolling hills of its eastern plains. Like Neill’s Russian submarine officer, those of us who live in a world starkly different from that which we imagine exists in Montana may find the idea of the state especially enticing. It just sounds peaceful. Maybe it’s the name.

Of course, some people hear “Montana” and think not of a pristine wilderness but of a football player—that blond, baby-faced quarterback who could throw on a rope to Jerry Rice. Besides Joe Montana, two other American heroes come to mind: Lewis and Clark. The path of their Corp of Discovery crossed the length of the state both coming and going, along the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers. To them Montana was part of the unnamed, undiscovered wilderness of North America, a frontier they were proudly conscious of penetrating.

People may also think of cattle, one of Montana’s largest industries. An old truism jokes that Montana has more cows than people, and in fact it does—about three times more. But really, this statistic speaks more to the relatively small population of Montana and to the carnivorous nature of humans—especially humans in the United States. And given the variety of markets Montana’s cattle industry serves, the statistic is really not so shocking. Besides a thriving beef production, the state also claims a lucrative dairy industry, as well as being a world leader in providing seedstock—cattle bred for the purpose of...well, breeding cattle.

One thing is for sure. When one envisions Montana, the picture is most certainly one of the outdoors. While we know, rationally, that buildings do exist within the borders of the state, there are none in our mental image. Concrete and steel just don’t seem to fit into the picture with all of those mountains, plains, and...cows.

Gold and Vigilantes

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 the region of Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas was commonly referred to on maps as “Indian Country.” It was almost completely uninhabited by white people, so Congress largely ignored it while struggling to organize those areas where Americans were settling. Then, in 1846 the U.S. signed a treaty with Great Britain continuing the 49th parallel border with Canada all the way to the Pacific Ocean. (It had previously only been recognized as far as the summit of the Rocky Mountains.) And in 1848 the Mexican government ceded all of California and “Eastern California” (Nevada, Utah, and parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming) to end the Mexican-American War.

In 1862 the Civil War fighting began to heat up and so did the Montana gold rush. Of course, it wasn’t Montana yet. It was Idaho Territory east of the Rocky Mountains. Prior to that, it had had many official names to the U.S. government. Parts of it had belonged to Washington Territory, Dakota Territory and Nebraska Territory, not to mention its earlier stint as part of Louisiana Territory. But gold-seekers cared nothing of names. Prospectors poured into the mining camps and with them came the lawlessness that historically followed. Vigilance committees, like those created in San Francisco in 1856, were responsible for twenty-two lynchings in the first two months of 1864.

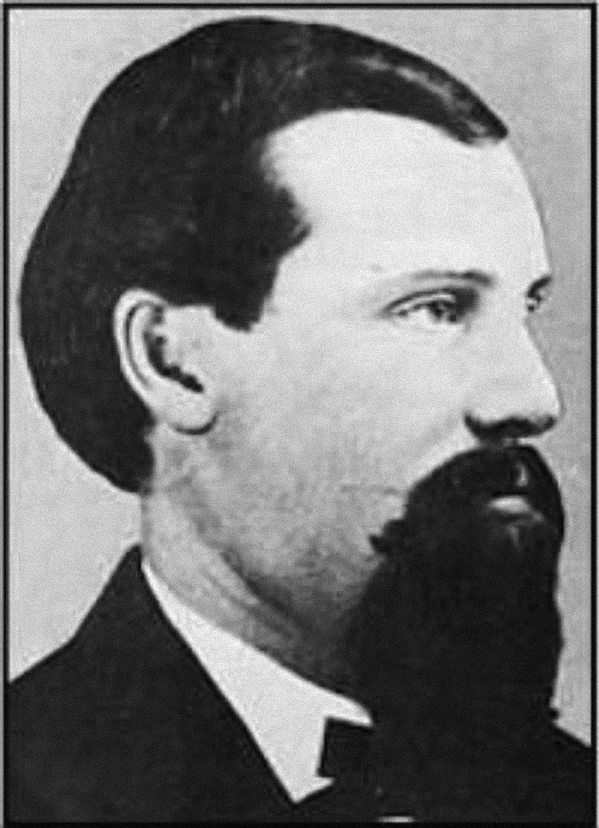

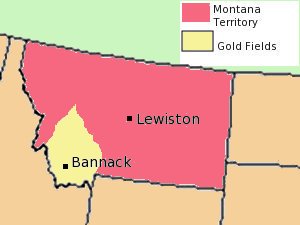

The most notorious of these lynchings was that of a man named Henry Plummer, a gambler and lawman who had come to Idaho to stake a claim in the fevered gold rush. He was hung by a mob in January of 1864 in the town of Bannack, Idaho Territory, for allegedly murdering a hated rival. The historical debate over Plummer’s guilt or innocence has fascinated Montanans for over a century and illustrates the murky lawlessness under which the people of the region operated. The citizens in eastern Idaho Territory wanted law and order, and the territorial capital at Lewiston was too far from the mine fields and the eastern plains to be of any use. They decided to appeal to the Federal government.

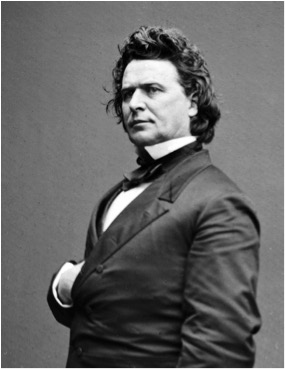

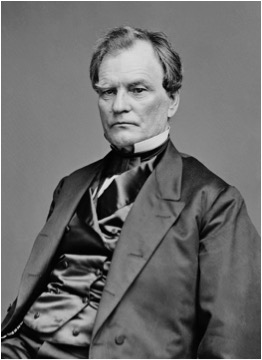

Edgerton and Ashley

The man sent to Washington to appeal for a new territory was Sidney Edgerton, former congressman from Ohio and known in Washington as a good Republican. Edgerton had been sent to Idaho in 1863 to be the Chief Justice for the territory, but instead of going to Lewiston to be sworn into office, he headed to Bannack where miners had recently struck gold, and a lot of it. Rather than establishing law and order for the region, Edgerton and his nephew, Wilbur Sanders, who had been sent along with his uncle as a federal prosecutor, became instrumental in the creation of Bannack’s Vigilance Committee —the one that hung twenty-two people including Henry Plummer.

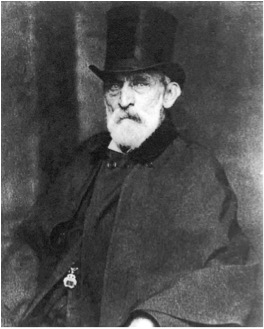

Nevertheless, Edgerton was the man chosen to lead the cause for territorial organization. He left for Washington in January of 1864 and wasted no time looking up his old friend James M. Ashley, chairman of the House Committee on Territories. From 1859 to 1863 the two men had represented Ohio together in the House of Representatives. Edgerton’s task was made fairly simple by the fact that the arguments for separating the eastern region from Idaho were sound, and that his political interests were friendly to the Lincoln administration and to Congress which was operating without the southern Democrats who had long since seceded. So the process proceeded quickly, as Ashley prepared and then introduced the bill proposing Montana Territory to the House of Representatives on March 17, 1864.

James M. Ashley would, in later years, become known as “The Great Impeacher” for his attempts to impeach and convict Andrew Johnson, believing he had been involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. But this reputation overwhelms many years of state-making which he accomplished as the Chairman of the Committee on Territories. Ashley held this chairmanship from 1861-1869, helping to engineer (and name) many of the western states.

The word “Montana,” which means “mountainous” in both Spanish and Latin, was a favorite potential state name of Ashley’s, one which he dearly wished to apply to any state that contained a section of the Rocky Mountains. He had originally applied the name to what became Idaho Territory, but another committee had changed that territory’s name to “Idaho,” and Ashley was quite disappointed. So when his friend Edgerton asked Ashley to propose a name for this new territory, he immediately suggested “Montana.”

Congress

The bill presented to Congress saw little opposition, though there were some details to be worked out, such as the appointment of judges and how much to pay them. There was, however, in the brief congressional debates, some discussion of the name. In the House of Representatives at least one man thought the name “Montana” meaningless until Ashley explained its Spanish derivation and definition. Another delegate offered the name “Shoshone,” preferring an Indian name to one imported from a European language. It was pointed out that the word “Shoshone” means “snake,” and the proposed name change was quickly abandoned. (The name “Shoshone” is now believed to mean “grass house people,” derived from the fact that certain tribes of Shoshone built their homes out of woven grass mats. The “snake” theory, however, persisted for years.) Other members of the House wanted to honor a statesman with the naming of the new territory, and the names Jefferson and Douglas were proposed. But these monikers “...met with little favor in a body dominated by Republicans.”1

When the measure arose in the Senate, there was still more discussion of the name. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts questioned the name “Montana,” claiming it “...strikes me as very peculiar...” and that it “...must have been borrowed from some novel or other.” Sumner stated he would prefer an Indian name, a name “from the soil,” but when pressed to suggest one, he admitted he did not know the region well enough to do so.

Senator Jacob M. Howard of Michigan quickly responded to Sumner’s curiosity about the name “Montana,” saying “...I was equally puzzled when I saw the name in the bill, and I ...was obliged to turn to my old Latin dictionary to see if there was any meaning to the word Montana, and I found there was...It is a very classical word, pure Latin. It means a mountainous region, a mountainous country.” Howard further championed the name saying “You will find that it is used by Livy and some of the other Latin historians, which is no small praise.”

Senator Benjamin Wade, who represented Ohio just as Ashley and Edgerton once did, summed up the entire discussion rather succinctly. Apparently wanting to move on to other topics, Wade noted, “I do not care anything about the name. If there was none in Latin or in Indian I suppose we have a right to make a name; certainly just as good a right to make it as anybody else. It is a good name enough.” And that was the end of the discussion on what to name Montana.

Indians and Statehood

The bill passed Congress fairly easily, and on May 26, 1864, Abraham Lincoln signed the Territory of Montana into existence. The next month he appointed Sidney Edgerton the first governor of the territory. James M. Ashley, the man who named the state, would also serve as governor of the territory a few years later. After leading the fight to impeach Andrew Johnson, Ashley failed to be reelected to the House of Representatives in 1869. As a consolation prize, the new president, Ulysses S. Grant, appointed him to the position of Montana governor, where he served for only one year.

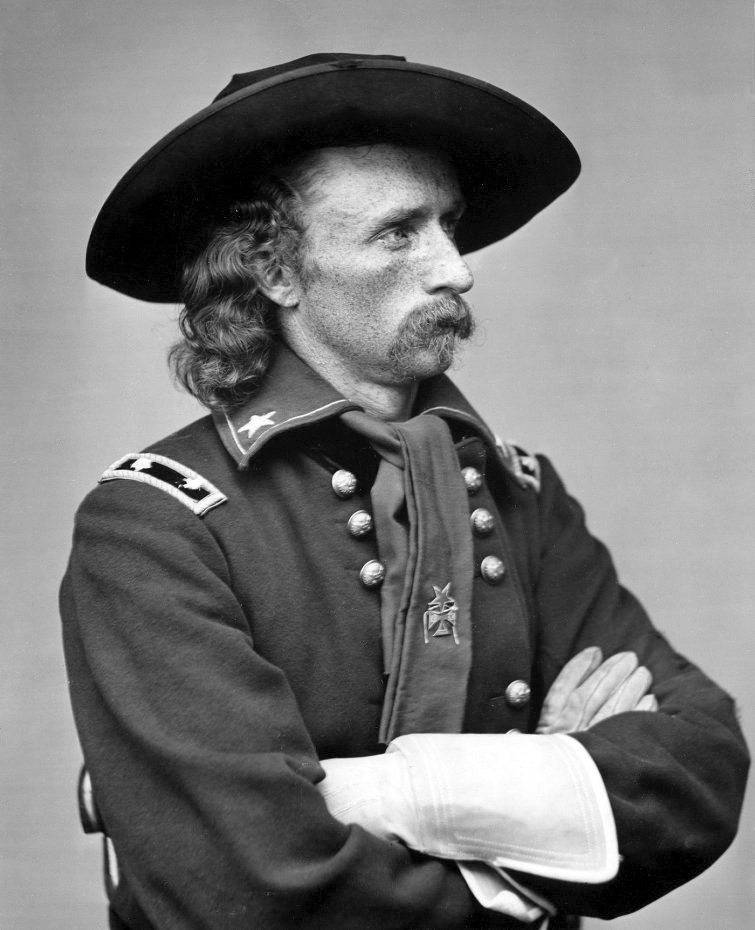

Some irony can be found in the attempt by Charles Sumner to replace “Montana” with an Indian name. Certainly the naming strategy in the creation of most of the western states commonly included aboriginal words, preferably—though not necessarily—words that applied to the region being named. But like most members of Congress, and most white Americans, Sumner knew almost nothing of the region he was proposing to name, and what he did know was of the few white Americans who lived there. But a decade after Sumner’s feeble attempt to apply an Indian name to the region, Montana would become the site of one of the most famous clashes between white Americans and native Americans—The Battle of the Little Bighorn , also known as Custer’s Last Stand .

The Little Bighorn battle marked the pinnacle of strength of the Sioux Nation in their escalating hostilities with the U.S. Army. But it was also the beginning of the end of American Indian wars. Skirmishes continued for the next ten years, but the support of white Americans was now with the U.S. army in its attempt to avenge the death of Custer and quell the Indian “threat” once and for all.

By 1888 several western states had languished in territory-hood for over a decade, and Congress was feeling the pressure to grant statehood to them all. An enabling act was passed by that year’s lame-duck session providing for the inclusion, pending constitutions and elections, of Montana, Washington, and the two Dakotas. On November 8, 1889, with the swift signature of President Benjamin Harrison, Montana became the 41st state in the Union. One year later final defeat of the Sioux was garnered one state away at Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

End Notes

1. Hamilton, James McClellan, From Wilderness to Statehood: A History of Montana, 1805-1900 (Oregon, 1957), p. 277