MISSISSIPPI

In 1814 we took a little trip

Along with Colonel Jackson down the mighty Mississip

—Johnny Horton, Battle of New Orleans

M-I-S-S-I-double S-I-double P-I

—Bobbie Gentry, Mississippi Delta

Why this state?

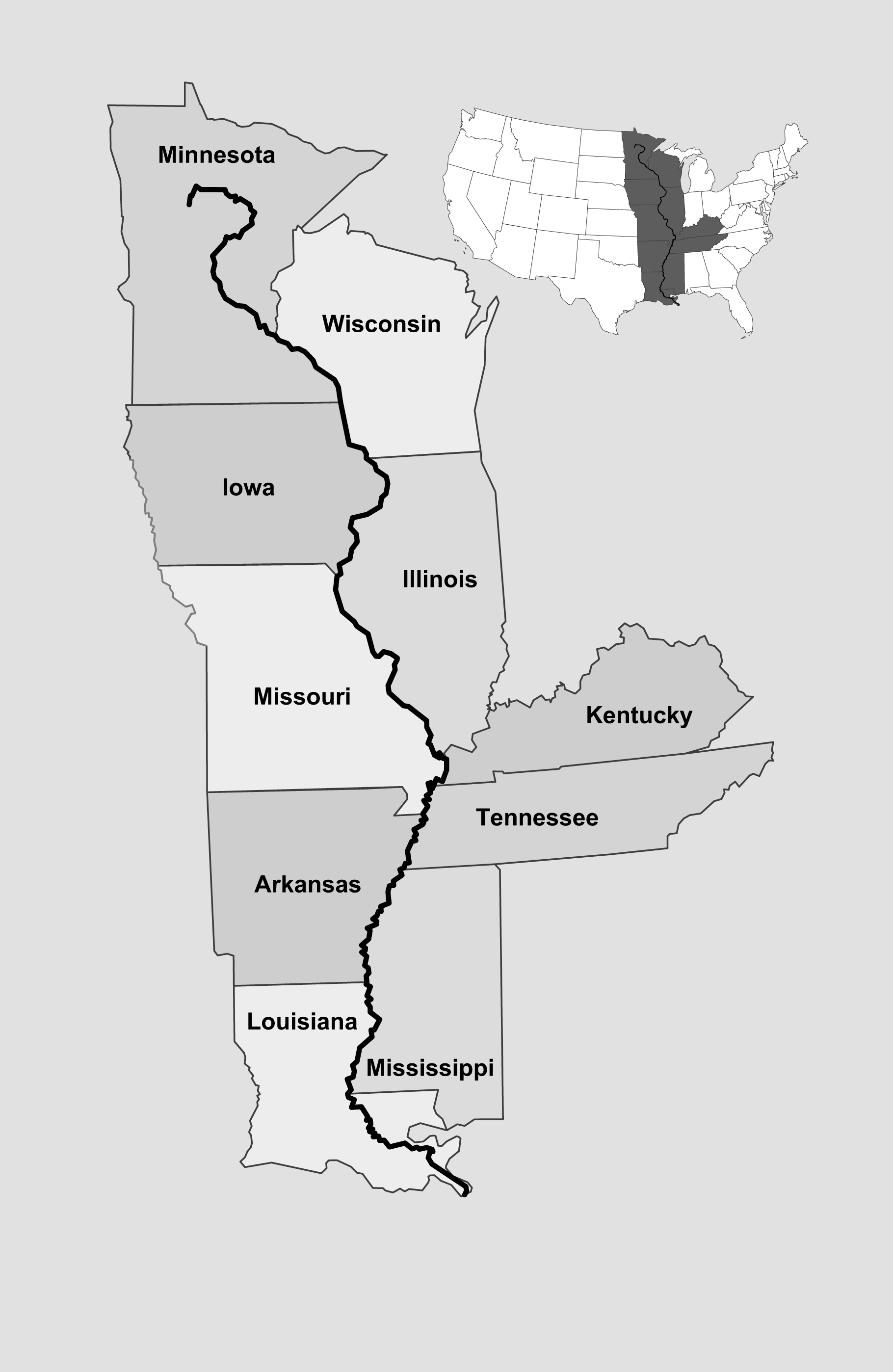

The Mississippi River touches ten U. S. States on its way from Lake Itasca in Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. Mississippi, the state, does not claim the longest border with the river (that would be Illinois), nor does it contain the source (Minnesota) nor the mouth (Louisiana). It is not the largest of those ten states (also Minnesota), nor was it the first of the ten to achieve territory or state status (Kentucky). The Native Americans who referred to the river as “Messisipi” were the Chippewas, encountered by French explorers near the southern end of Lake Michigan. The Gulf Coast natives, those who actually inhabited what is now Mississippi State, had an entirely different word for the river, “Malbouchia”. So how did Mississippi, the state, come to bear the name of the mighty Mississippi river?

The answer to that question is vague, but lies in the context of the history of both the river and the state. Indeed, both were known by different names by early European discoverers and settlers—in the case of the river, by many different names.

Of course, as a national landmark, it is difficult to beat the Mississippi River in sheer size and volume. Its importance in American history, culture, industry, and commerce is virtually unchallenged by any other natural resource. The mighty river and its banks gave us Mark Twain, riverboats, a massive trade route, and many different tribes of Native Americans who thrived for hundreds, even thousands, of years on her life-giving currents. When combined with the Missouri it is the longest river in North America, and the fourth longest in the world.

The state of Mississippi, however, has a reputation all its own. Besides the obvious “How do you spell that?,” the state calls to mind “The South,” with all its various images: slavery, the Civil War, southern belles in big hoop skirts, Baptist churches, and thick accents.

One image that Mississippi harbors, though certainly wishes it did not, is that of a poverty-stricken population. It is not an image the state wishes to proliferate, but alas, it need not bother. The state has the highest poverty rate in the country, with many of its western counties—those situated adjacent or very close to the Mississippi River—suffering poverty rates above thirty percent. This has been a misfortune of the state’s since the first farmers began to scratch at the land, one that has been burned into our imaginations.

But a 2009 book called “The State of Jones” by Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer reminds us to be careful of our assumptions about Mississippi and its people. It tells the story of Newton Knight, that rarest of creatures, a southern abolitionist who, like his counterpart in the north, John Brown, fought a very personal war not only against slavery, but against bigotry and racism.

For our purposes, it also chronicles the creation of what Knight and his compatriots regarded as a state separate from (but within) Mississippi, one where slavery did not exist, and would not be tolerated. And to punctuate their newly created “state,” Knight and his men gave it the name of the county they were proud to protect and dominate, creating a new and difficult front for the South in the Civil War.

The Lower Mississippi River

Hernando de Soto is generally acknowledged as the first European to discover the Mississippi River. He didn’t name it, however, for it already had a name to the Spanish. It was named “Rio del Espiritu Santo” or “River of the Holy Ghost” by Alonzo Alvarez de Piñeda who had explored the Gulf Coast in 1519 and applied this name to the mouth of a river he described as “very large and very full”1. Later historians guessed that the bay he referred to was actually Mobile Bay.

“Espiritu Santo” appears in 1521 on a map drawn to arbitrate the claims of rival discoverers. On this map the region of the Mississippi belongs to Francis de Garay, governor of Jamaica who had commissioned Piñeda’s voyage. Garay’s dominion was unimpressive by Spanish standards, however, for it was believed to be “too far from the Tropics” to contain gold2, and given the riches they plundered from Mexico and South America, Spain wanted virtually nothing else from its New World explorers.

The actual mouth of the Mississippi was likely found by Cabeza de Vaca, the treasurer for an expedition that began in 1527 led by Panfilo de Narvaez. Narvaez was, by all accounts, a brutal and selfish conqueror. He marched his men inland from Tampa Bay where they were molested by natives not, presumably, unprovoked and turned back toward the sea. They constructed boats from the hides of their horses and set sail for civilization. Narvaez was never seen again, but de Vaca lived to recount his tale. In it, he describes what historians believe truly was the mouth of the Mississippi (though de Vaca had no name for it). In their makeshift boats a few of the survivors attempted to enter the mouth of the great river, but, de Vaca wrote,

“By no effort could we get there, so violent was the current on the way, which drove us out, while we contended and strove to gain the land.”3

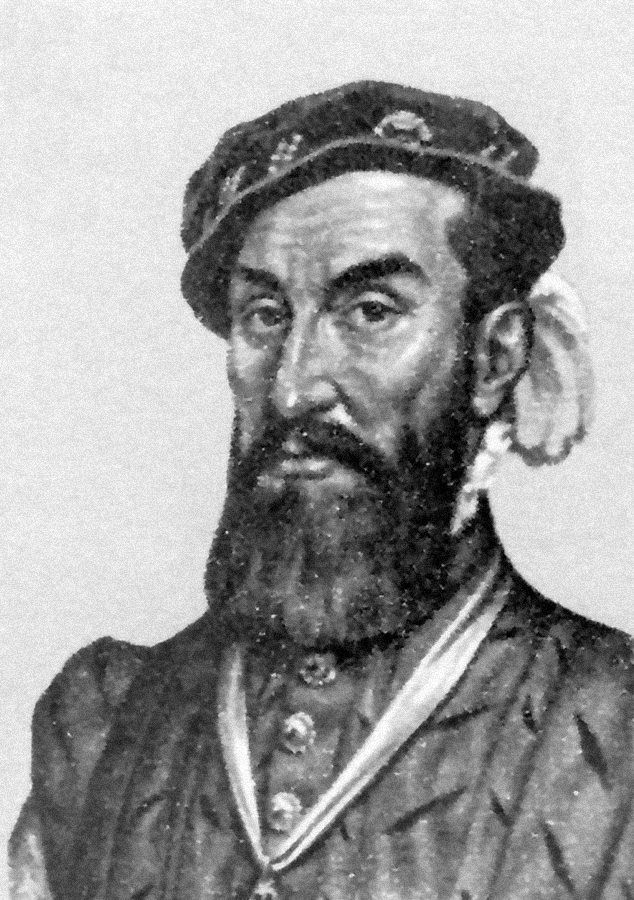

De Soto’s efforts were no less futile. His expedition of several hundred men began in 1539, again at Tampa Bay. They marched through the southeastern United States, confronting the natives with almost comical self-importance and belligerence. And when they encountered the mighty Mississippi River it was viewed as an irksome obstacle to be crossed in their quest for treasure, not the majestic waterway that would eventually become such a coveted trade route. De Soto’s status as discoverer of the river can only be attributed to the fact that he musthave crossed it, and the chronicler of his journey, the Gentleman of Elvas, refers to a river which he calls the “Rio Grande” that probably is the Mississippi. Arguably de Soto’s most compelling claim as the Mississippi’s European discoverer is that he was reported to have been buried on its banks.

The Upper Mississippi

After De Soto, the Mississippi went unexplored by Europeans for about a hundred years, after which the French began to close in on its banks in the north. The French explorers differed from the Spanish in almost every way. They were not conquerors but traders and missionaries. They befriended the natives whenever possible (though fought them when they felt it necessary) and generally maintained a healthy respect for their tenacity and willingness—not to mention right—to defend their homeland.

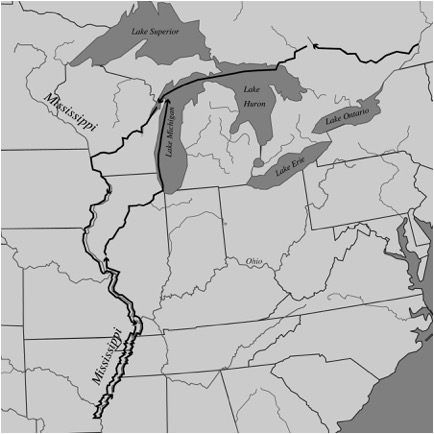

In 1634, French explorer Jean Nicolet journeyed up the Fox River in present day Wisconsin, where he was told by Winnebago tribesmen that there was a river nearby which flowed into the “great water.” He did not see the river, nor the tributary which the Indians described, but the “great water” he was told of was the Mississippi River.

The first written instance of the river’s current name appears in the Jesuit Relation for 1669 to 1670 . It was reported by Father Allouez, who had traveled as far as the Wisconsin River, that the “Messisipi,” as his Chippewa guides referred to it, was more than a league wide, that it flowed north to south, that the Indians had never traveled to its mouth, and that it was doubtful whether it emptied into the Gulf of Florida (meaning modern Gulf of Mexico) or the Gulf of California.4

In 1673 a French fur trader named Louis Joliet accepted a commission to explore the “Messipi,” translated as the “Great Water” or “Father of Waters.” He was accompanied by Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Missionary. The two men explored the Mississippi as far south as the Arkansas River where they encountered Indian tribes in possession of Spanish trade goods. Fearing they would be captured by Spanish forces and imprisoned, the Frenchmen turned back toward Canada. Unfortunately at the end of their journey, Joliet’s maps and notes of the expedition were lost in an attempt to shoot a set of rapids in a frail canoe. Joliet himself barely escaped with his life and later tried to reconstruct his journals, but much detail was lost. Marquette’s notes were used to fill in the blanks, but he was more a missionary than an explorer, and his accounts were of little consequence except that for some time after the expedition of Joliet and Marquette, the Mississippi River went by Marquette’s name for it, “Riviére de la Conception.” In one of Joliet’s reconstructed maps the Mississippi is referred to as “Riviére Colbert.” Jean Baptiste Colbert was a powerful Minister in the court of King Louis XIV and a driving force behind French exploration efforts.

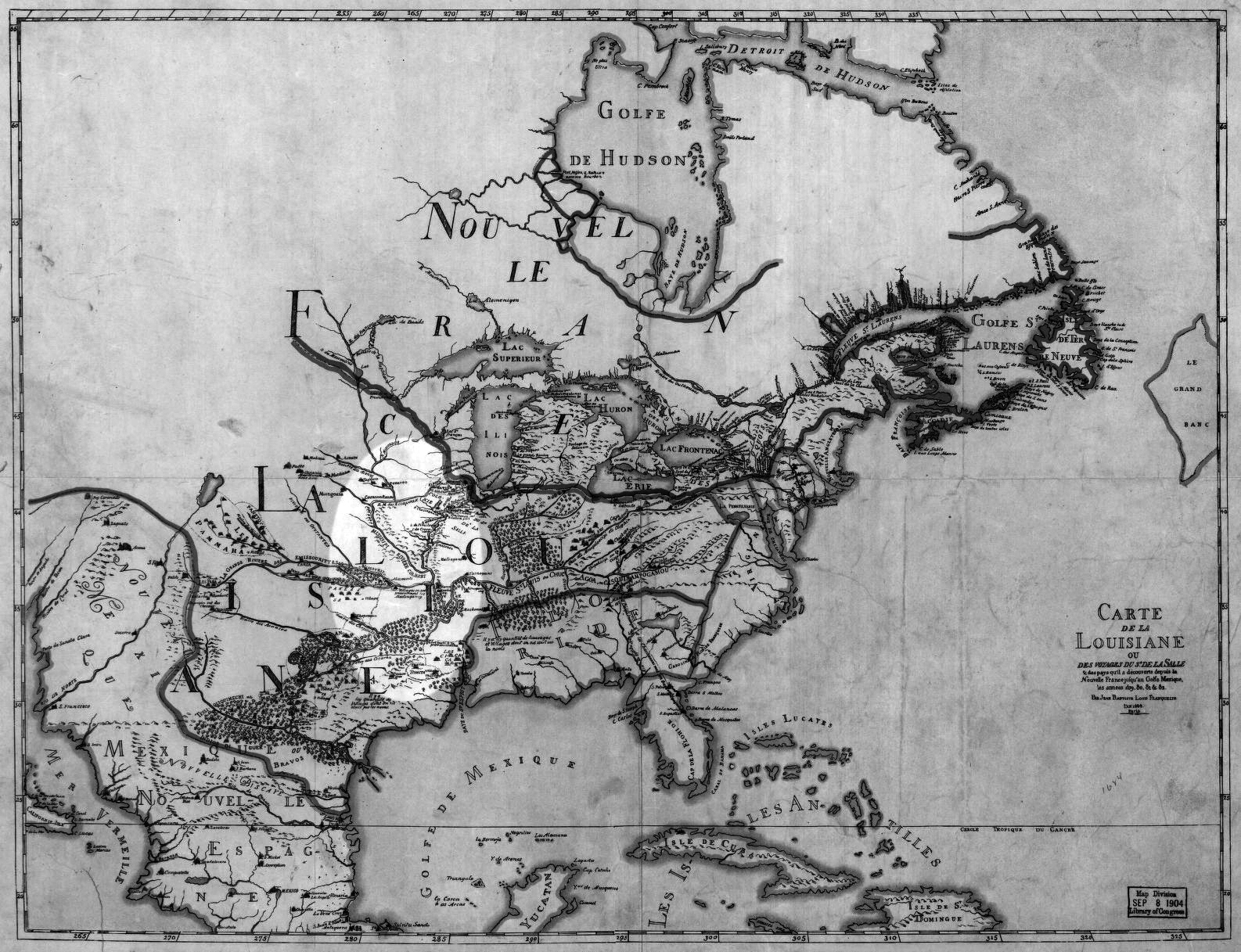

By the time Rene Robert Sieur de La Salle navigated the Mississippi to its mouth in 1682 and claimed its banks and tributaries for his King, the river had no less than ten names. Besides those already mentioned it also appeared on Spanish maps as “Rio Escondido,” on French maps as “Buade ou Frontenac,” the “St. Louis,” “La Palisade,” and the “River of Louisiana.” Other Indian tribes called it “Chu-ca-gua,” “Mal-bok-a,” and “Namese-sipon.”5 Even the name by which we now call it had, as one might imagine, countless different spellings since its written form relied upon the phonetic disposition of the writer.

In 1684, Jean-Baptiste Louis Franquelin was the official court cartographer for the French governor-general in Quebec. It was his map which became the standard for French traders and missionaries, and Franquelin chose to use the Chippewa name first recorded fifteen years earlier by Father Allouez. Even though he badly misplaced the mouth of the river and made no attempt at its source, Franquelin correctly drew the Mississippi River dominating the central plains of North America.

Mississippi River dominating the North American interior.

Dividing the Land

By 1762, Spain and France had become allies in an all-out world war against England, one which France was losing. American history calls it the “French and Indian War,” but that name seriously confuses the combatants (implying that the French were fighting against the Indians). The hostilities were more accurately part of the Seven Years War, a global battle fought with England and Prussia on one side, France, Spain, Austria and Russia on the other. The term “French and Indian” refers to the fact that in the interior of the North American continent, where France and England were the principal powers fighting for dominance, the Indians generally sided with the French, hoping to drive the land-hungry British back to Europe. Spain gets no billing because her footing on the North American continent was quite tenuous, holding only Florida and a few coastal colonies along the Gulf of Mexico. That however, would change with the war’s outcome.

In 1763 the Treaty of Paris was signed to end the Seven Years War, and new borders in North America were established. France, as a controlling power, was removed from the continent, and the land was effectively divided between England and Spain, the border between them being the Mississippi River. England, of course, received the thriving, colonized eastern half of the river basin, and Spain, who was on the losing side of the war, was compensated for more critical losses (namely Cuba), by gaining the relatively unexplored and, at the time, strategically unimportant western half—all the land in between the Mississippi River and the continental divide of the Rocky Mountains.

With the 1763 treaty the mighty river, instead of defining the region of its watershed, uniting its eastern and western banks, now served to divide the land. The river became a dominating border, and remains so today. Every state that touches the river also uses it as a border with a neighboring state. Even at its source, where Minnesota is divided from Wisconsin by a section of the Mississippi, and at its mouth where Louisiana is separated by the Mississippi from the state that bears the great river’s name, the river has become, to paraphrase former U.S. President George W. Bush, “a divider, not a uniter.”

The West Florida Controversy

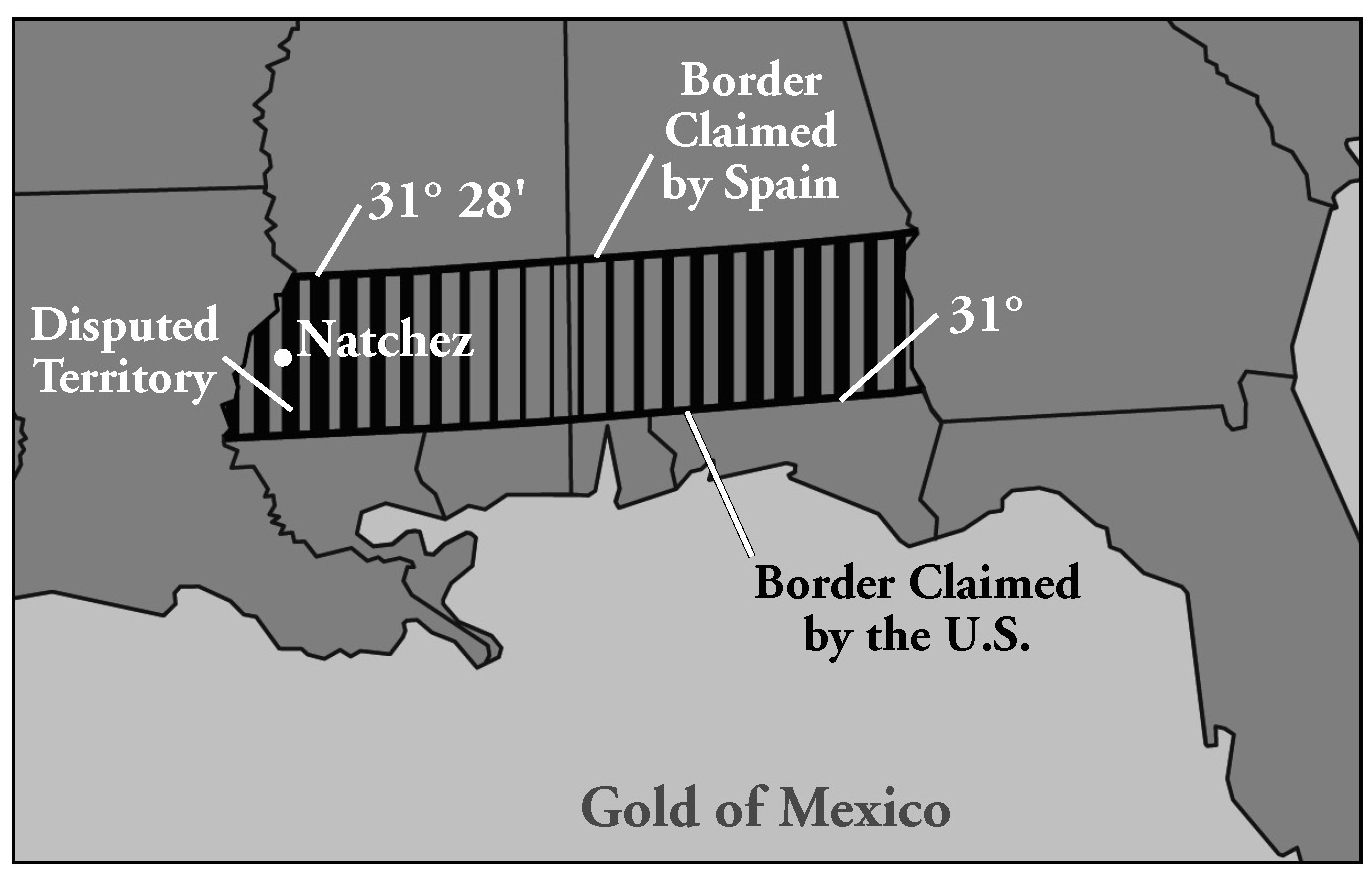

By virtue of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, England received Florida from Spain, roughly all of the current state of Florida plus the coastal colonies of the Gulf of Mexico. This included what the British named “West Florida” which “was bounded on the west by the Mississippi River, on the east by the Appalachicola River, on the south by the Gulf of Mexico, and on the north by the northern shores of Lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain and at 31 degrees north latitude.”6

In 1764 the British government made a decision that would touch off one of the most complicated border disputes in American history, and it involved the southern portion of the current state of Mississippi.

Finding that the fertile settlements ofNatchez fell north of the northern border of British West Florida, the British Board of Trade moved that border slightly northward to 32°, 28’. British West Florida now lay below that parallel, and above it, the British colony of Illinois.

During theAmerican Revolution the colony of British West Florida was a loyalist haven which went unmolested until 1778, when Captain James Willing attacked the settlements in the Natchez District. When France and Spain entered the war on the side of the U.S., Spain quickly took Natchez by force, and at the end of the Revolution, Spain was once again given control of the Floridas.

Thus began the dispute. By the 1783 Treaty of Paris, Britain ceded to the United States the territory between the Appalachians and the Mississippi south to the 31st parallel. She ceded to Spain the colony of British West Florida without reference to its northern border, a border which Britain had moved in 1764 to 32°, 28’, to include the coveted Natchez District. Both Spain and the United States claimed the land between 31° and 32°, 28’, but Spain held it by force, and so without going to war again, “the United States could only protest diplomatically.”7

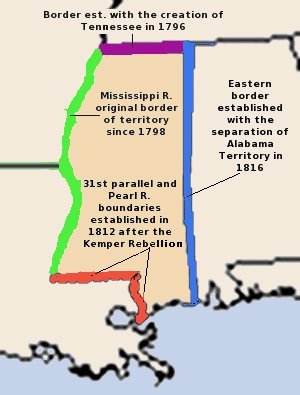

By the 1790s Europe was caught up in the French Revolution, and the United States was pushing westward full force. Spain felt the encroachment of the Americans, and in 1795 the two countries signed the Treaty of San Lorenzo (also called Pinckney’s Treaty) which gave Americans the right to navigate the Mississippi River, and finally settled—in favor of the United States—the disputed northern boundary of West Florida, placing it at the 31st parallel. For three years Spain dragged their heels in evacuating the Natchez District, but on March 30, 1798, the last of the Spanish forts was vacated. A week later, on April 7, the U.S. Congress created the Territory of Mississippi.

Territory and State

The borders of the Territory of Mississippi originally bore little resemblance to those of the current state. The western border was the Mississippi River, and along it the district of Natchez was still the most populated region in the new territory. The state of Tennessee marked the northern border, and the Chattahoochee River the eastern. In 1802 the U.S. persuaded Georgia to cede its claim on the lands west of the Chattahoochee, land the U.S. already considered part of the new Mississippi Territory. In 1810 settlers in West Florida rose up against Spanish rule and, in 1812, asked the United States for annexation. The U.S. gave that portion of West Florida between the Mississippi and the Pearl River to Louisiana, and a year later gave to the territory of Mississippi the region between the Pearl and the Perdido. Thus, by 1813 the Mississippi Territory contained all of the land now included in the states of Mississippi and Alabama.

The new territory, from the time of its earliest formation, was already divided economically and socially. The western settlers had become the large cotton plantation owners, while the easterners tended to be smaller farmers of corn and cattle.8 In March of 1817 the division became official with the creation of the Alabama Territory, and the Mississippi Territory, now with the borders it would carry on to statehood, began the process of electing officials and drawing up a constitution. On December 10, 1817 President James Madison signed the Act that would make Mississippi the twentieth of the United States of America.

End Notes

1. Severin, Timothy, Explorers of the Mississippi (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968), p. 12.

2. Severin, p. 12.

3. Severin, p. 92.

4. Childs, Marquis, Mighty Mississippi: Biography of a River (New York, 1982), p. 7.

5. Claiborne, J.F.H., Mississippi as a Province, Territory, and State (Jackson: Power & Barksdale, 1880), p. 32.

6. Skates, John Ray, Mississippi: A Bicentennial History (New York, Inc., 1979), p.32.

7. Skates, p. 44.

8. Skates, p. 68.