MINNESOTA

“My governor can beat up your governor.”

—Bumper sticker emblazoned with a picture of Jesse

"The Body" Ventura, governor of Minnesota 1999-2003

“There goes my Minnesota girl”

—Green Day, Minnesota Girl

“I’m looking California,

and feeling Minnesota.”

—Soundgarden, Outshined

True Colors

It is difficult to say the word “Minnesota” without adopting the manner of natives of that state—a sing-songy lilt with the third syllable drawn out and a puckering of the lips: Min-nuh-suōōō-tuh. And then it makes us smile.

In fact, just about everything about Minnesota makes us smile: the Mall of America, Former Governor Jesse “The Body” Ventura, Senator Al Franken, and Gophers. Even the nickname of its two largest cities, “The Twin Cities,” seems all-together non-threatening, and even pleasing, as if the cities it refers to were two young children who look and dress alike but somehow resent being confused with each other.

The word Minnesota is a Dakota word which means “sky-tinted water” or “somewhat clouded water” (“minne” for water, and “sota” for cloudy or bleary). One missionary in the 1800s told of having a Dakota illustrate the definition of the word to her by dropping a teaspoon of milk into a glass of clear water. This native was describing the Minnesota River which displays a whitish hue during some spring seasons, when the river swells and the light-colored silt along the banks crumbles into the water.

As one historian notes, a recent advertising slogan has led many to believe that Minnesota means “land of sky-blue water.” An apt comparison could be drawn to the state’s citizenry—calm and placid on the surface, but with the ability to stir the waters and surprise the rest of us, stirring a cool blue into a myriad of surprising colors.

Territory after Territory

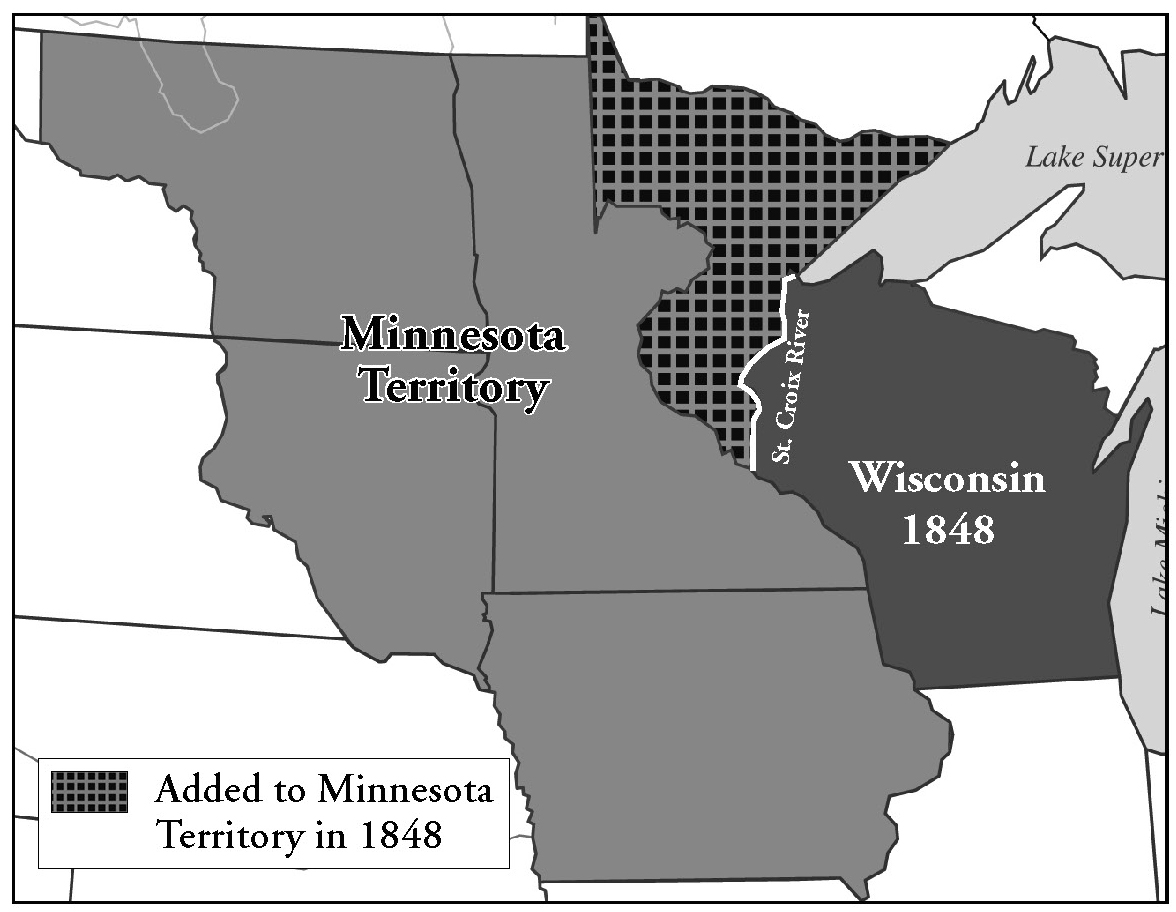

The Territory of Minnesota was conceived at the very height of westward expansion in the U.S. After the Northwest Territory had been carved up into individual states, Manifest Destiny took hold and the organization of the rest of the continent into territories and then states was virtually a foregone conclusion. All that was left to do, in the minds of many an enthusiastic expansionist, was to draw borders and assign names. Wisconsin , in 1848, was the last of the Northwest Territories to be granted statehood, but instead of keeping the western border of the territory, the Mississippi River, Congress decided to chop the St. Croix valley in half and use that river as the state’s new western edge.

This was done in part due to a pragmatic desire to keep the size of each state manageable and in part due to a partisan political phenomenon. Once statehood became imminent for a particular territory, congressmen would look westward, salivating at the prospect of adding more states, and therefore more representatives in Congress. Democrats wanted to create more Democratic states, and Whigs and Republicans wanted to create more for their own party. Slave-holders wanted more slave states, and abolitionists lobbied for more free states. The same motivations would play out over and over again, notably in the prairie and mid-western states, and was often a major cause of delay in any territory achieving statehood.

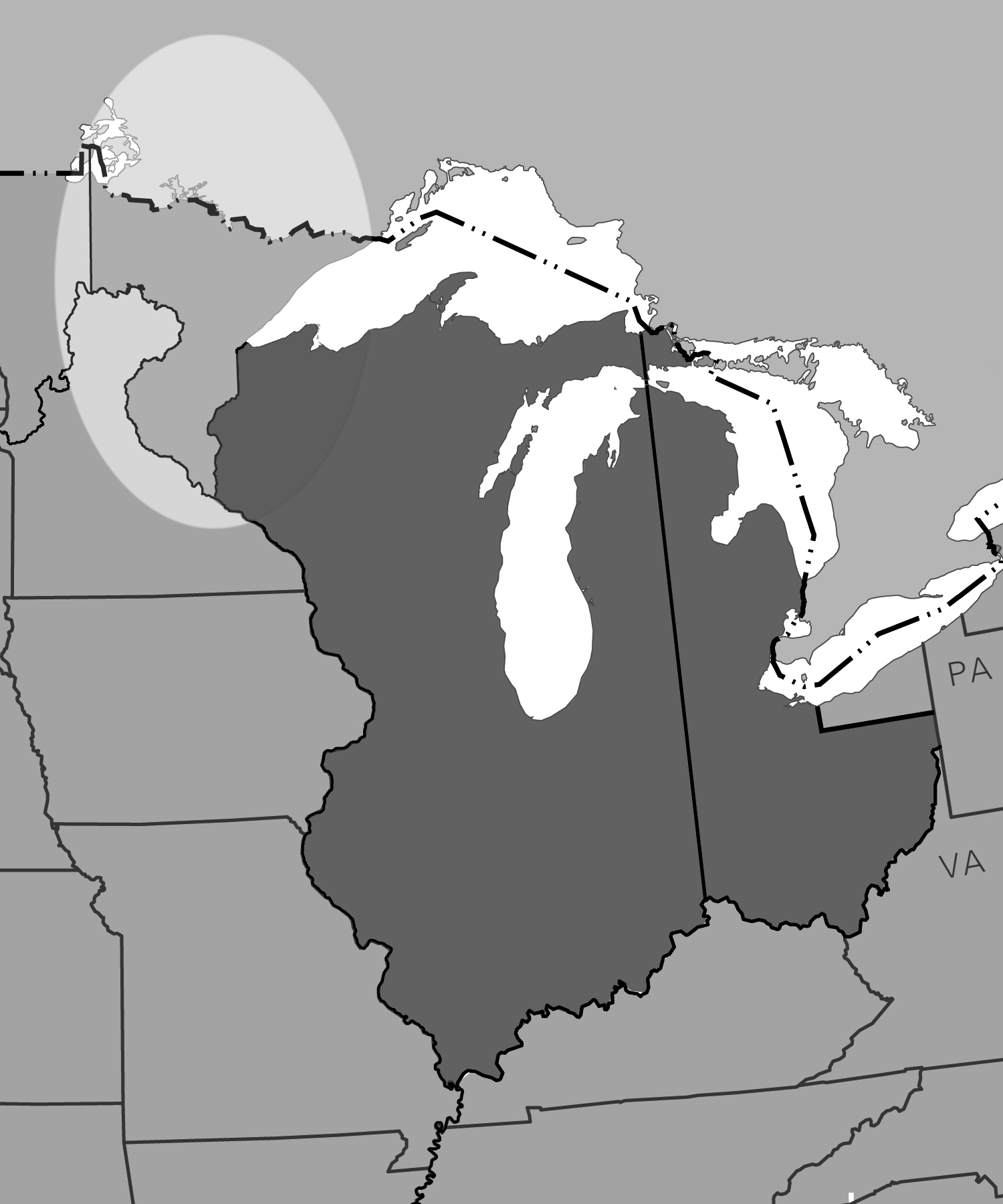

The U.S. claimed the land that is now the northeastern portion of Minnesota in 1783 after the Revolution. It was part of the Northwest Territory (for which the Northwest Ordinance was written—see Ohio) and was one of the spoils won from the British and their Indian allies, or at least that was the view of the U.S. government. Technically the region was claimed by Virginia as part of her original charter, but she readily ceded it to the new nation for stewardship under the federal government. The western portion of Minnesota would not be claimed until after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

But after 1803 the land was part of a long series of territories. Each time a state was formed by separating an eastern chunk of populated land from an established territory, the new state would usually take the name of the territory, leaving what was left over to be given a new name (and often new borders.) Minnesota, or some of it, had been part of the Northwest Territory, as well as the Territories of Indiana, Louisiana, Illinois, Missouri, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa.

Martin and Brown

“To many easterners Minnesota was an almost wholly unfamiliar name,” writes one historian, “and they had no idea where the territory really was.”1 It was in 1846, when Wisconsin was still lobbying Congress for statehood, that the name “Minnesota” was proposed for the western portion of the territory that would not be included in the new state. It was possibly the first time most of the Congressmen had ever heard the word uttered, and the person who uttered it was Wisconsin’s territorial delegate, a lawyer named Morgan L. Martin. Martin would later claim that, while serving in the Wisconsin legislature he learned the word from a colleague, a former soldier and adventurer named Joseph Renshaw Brown. Unlike Martin, who lived in Green Bay, Brown lived near St. Paul and had served at Fort Snelling. He would have known that the Dakota Indian name for what Americans called the “St. Peter River” was Minnesota.

Martin’s speech to Congress in 1846 was a plea for statehood for Wisconsin but included a proposal for the “organization of the Territory of Minnesota” as a way of disposing of those lands which would be left out of that state. Dominant in the proposed new territory was the Mississippi River, but that name, alas, was taken. Another prominent waterway was the St. Peter, but that name was inappropriate due to its religious overtones, and besides, Indian names were “all the rage.”

Martin’s bill was sent to committee where three other names were suggested for the new territory: “Itasca,” “Algonquin,” and “Chippewa.” Itasca has an interesting derivation of its own. It was coined by Henry R. Schoolcraft, the explorer who located the "source" of the Mississippi River. On his journey, Schoolcraft asked a colleague if he knew the Latin phrase for “true source.” The best his friend could come up with was “veritas caput,” or true head . Schoolcraft took the last four letters of the first word and the first two letters of the second to create “Itasca,” and used the word to name the lake he believed to be the actual headwaters of the Mississippi River—once he found it. When Morgan Martin’s bill came out of the Committee on Territories, chairman Stephen Douglas referred it to the House with the recommendation that “Itasca,” and not “Minnesota,” be the name of the new territory.

When the House of Representatives debated the bill, two more names were proposed: “Jackson” and “Washington.” At this point Martin suggested that his original name be returned to the bill, and not being able to agree on a replacement, the House passed the bill containing its original name, “Minnesota.” The senate rejected it. Two years later Minnesota would gain the territorial status it sought, and by that time, the name was much more popular and so was not debated.

As a territory, Minnesota contained all the land within its current borders plus half of North and South Dakota. Not until it became the 32nd state on May 11, 1858—President James Buchanan affixing his signature to the statehood Act—was the western border moved to its present location.

The Suland and the St. Peter

In 1851 a famous treaty—famous largely for its controversy—was signed with the four bands of Dakota Indians who lived along the Minnesota River. In the Treaties of Traverse de Sioux and Mendota these four bands, which comprised a division of the Sioux nation, relinquished their rights to the Minnesota River valley, and the land rush for the Suland (“Sioux land”) began. Though when the word was coined is not exactly clear, it appeared in newspapers of the time as the name for a vast section of southern Minnesota which was now available to settlers.

Interestingly, in the treaty the name of the river which the Dakota were being asked (many historians say “coerced”) to give up was “Minnesota.” This is notable because, since the 1600s when the river was first discovered and mapped by French explorers, it had been known as the St. Peter or St. Pierre River. It was Jonathan Carver, a British explorer and cartographer who spent the winter of 1766-67 near St. Anthony Falls (near modern downtown Minneapolis), who first recorded the name “Menesotor” in his popular book “Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America” and on the accompanying map. But by Carver’s time, “St. Peter” was already entrenched as the river’s official name.

The fact that “Minnesota” appears on the Treaty of Traverse de Sioux reflects the fact that, in the six years from the time the name was first proposed for the territory, it gained widespread use as the official “American” name of the river as well. Just to remove any confusion, however, on March 6, 1852, the Minnesota legislature petitioned the U.S. government, asking that the aboriginal name be used in place of the traditional “St. Peter” for all official government purposes. An act of Congress confirmed the name change on June 19th of that year.

End Notes

1. Theodore C. Blegen, The Land Lies Open (Minneapolis, 1949) p. 151.