MICHIGAN

Old Michigan steams like a young man’s dreams;

The islands and bays are for sportsmen.

—Gordon Lightfoot from

The Wreck of the Edmond Fitzgerald

“Si quaeris peninsulam amoenam, circum spice” (If you are seeking an amenable peninsula, look around you)

—Michigan state motto

Cars and Coastline

There’s a bit of onomatopoeia in the name Michigan. Hear it? The firing of the pistons, the roar of the engine, the car rolling off of the assembly line in Detroit or Flint. The name Michigan seems to exude industrialism, factories, and manufacturing. Since the start of the 20th century, and the introduction of the first horseless carriage, a majority of the newly manufactured cars in the United States have been built in Michigan (though admittedly, in recent decades many other states have invited automobile manufacturing plants into their borders, particularly in the southeastern U.S.). Ford, Oldsmobile, and GM all originated in this state, as did the United Auto Workers Union. Detroit, Michigan’s largest city, and the tenth largest city in the country, has borne the nickname “the Motor City” since the 1940s.

Of course, the more common version of this nickname is “Motown,” a word associated with an entirely different industry. Berry Gordy, Jr., the man who founded Motown Records in the late 1950s, once worked on Henry Ford’s automobile assembly line. But Gordy would not become idolized for his fundamental contribution to the automobile industry. Instead, he and Motown Records are credited with first introducing the world to such legendary musicians as The Miracles, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, The Jackson 5, and The Temptations, and for playing a significant role in the racial desegregation of pop music.

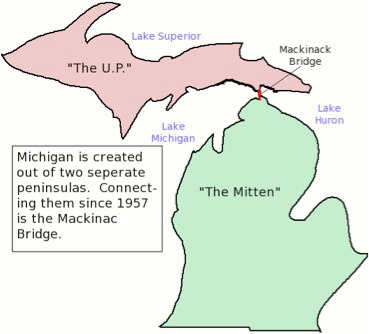

But perceptions of the state of Michigan have largely to do more with its geography, perhaps than with its industry. It is the only state that is formed out of two completely separate portions of the continent, though probably a little less separate since the opening of the Mackinac Bridge in 1957. The combination of these two peninsulas under one governmental organization is a curiosity to the uninitiated, and sometimes even to the initiated. The northern peninsula—cleverly titled “Upper Peninsula”—makes more sense as a continuation of Wisconsin than part of Michigan, while the main, or southern, peninsula fits more appropriately as part of Indiana, Ohio, or even Canada.

Movements to create a separate state out of the Upper Peninsula, or “U.P.”, or to somehow separate it from the rest of the state have brewed at varying intensities almost since Michigan’s formation. In the 1800s such movements proposed “Huronia,” “Superior,” and “North Michigan” as names for a separate state, sometimes including several northern counties of Wisconsin. Oddly, even though they are both peninsulas, it is the upper that is commonly referred to as such. The southern, mitten-shaped, portion of Michigan is rarely called the “Lower Peninsula” or even “Southern Peninsula,” though that’s exactly what it is.

With borders that touch four of the five Great Lakes in addition to thousands of islands, Michigan, deceivingly, has more coastline than all but one other state (Alaska). The largest of the islands included within her borders is Isle Royale, a roadless national park of an archipelago, sitting much closer to Canada than to either Michigan peninsula.

Like Alaska, Michigan is known for its abundant game fishing. Fishermen (and fisher-women) come from all over the country to cast out into the deep blue waters of one of the surrounding lakes—both great and small, hoping for the opportunity to catch one of the many species of fish found there.

A Stumbling Block

The French were the first Europeans to explore the Great Lakes and the first to map them and place names upon them. They took their own name for Lake Michigan from the Fox Indians, who referred to a neighboring tribe as Ouinpegouek or “People of the Stinking Water,” a reference to the algae-rich waters near that tribe’s home. The French mistranslated the name into Lac des Puans, or “Lake of the Stinking People.” Fortunately, like their names for several of the Great Lakes, this one would not last.

Later explorers and cartographers would label Lake Michigan Lac du Illinois for the nearby Illini Indians, Lac St. Joseph for the St. Joseph River to the south, and Lac Dauphin for the son of the French king. Finally, a popular map of 1688 used a derivation of the name that had been offered by Father Louis Hennipin, Michigami.1

Hennipin applied the name he heard used by natives during his explorations, but a precise derivation or definition of the word has proven elusive. It is certainly based in the same root as Michilimackinac , which, as an excellent history of the state by Bruce Catton puts it

“…is a stumbling block for anyone who writes or talks about Michigan. There are innumerable ways to spell it, there is argument over its meaning, and there is no logic whatever to its pronunciation; on top of which, it does not stay put properly as a historic place should.2”

Catton dismisses the notion that the name originally meant “great turtle,” a persistent myth based on the perceived shape of Mackinac (pronounced Mak-i-naw) Island from a distance that has its defenders even today. Catton based his own theory on an interview with an Ottawa Chief who insisted that the name referred to a tribe of people who once lived in the northern tip of the lower peninsula.

George Shankle’s reference book on state symbols also reflects the frustration of determining the origin of this state’s name:

“It would be a noteworthy accomplishment indeed, to be able to say authoritatively just who first gave the name Michigan to the Territory which now forms the State of Michigan, and from what exact Indian word it came.”3

The closest we may be able to come is this: the word Michigan is derived from some other, probably much longer, Indian word that is likely of Algonquian origin. Based on the language stock of the tribes who inhabited that area during the seventeenth century, Michigan is often referred to as an Ottawa or Chippewa word, but that is not provable. What is even less provable is to what someone might have been referring when they used the word. A group of people? A plot of land? A body of water? Or perhaps something else entirely.

Joseph Harrington, author of a Smithsonian report on state names in 1955, asserts unambiguously that the word means “clearing” but the dearth of references to support his assertion makes that definition entirely unsatisfying. Still, the translation “clearing” has become ubiquitous and is commonly offered today as fact. Others claim the word means “lake” or “large body of water,” but it is clear that these definitions originated after the word was applied by Europeans to the lake and the land.

Water, Water Everywhere

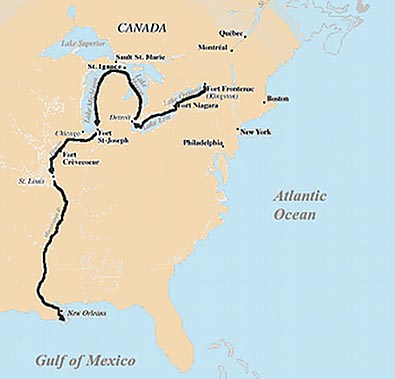

Michigan’s surrounding waters have historically been her life blood as well as her instrument of isolation. Throughout the seventeenth century Europeans (primarily the French) skirted the shores of Michigan, rowing and sailing their boats around the peninsulas in search of that ever-elusive water route to the other side of the continent. They set up the missions of Sault St. Marie and St. Ignace on the northern side of the straits of Mackinac (the narrow point that separates the two parts of Michigan), but the lower portion was relatively unexplored on the interior, simply because it was just too easy to get around it. The French were primarily trying to get past Michigan, and they didn’t need to get out of their boats to do it, so on they went, all the way through Wisconsin, and after a short portage, down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico.

Detroit was built to protect—not the land—but the water routes. The French, who were engaged intermittently in warfare with the English, constructed Fort d’Etroit on the river to which the same name was applied, in order to protect their monopoly on the navigation of the Great Lakes. Thus they would be able to keep the English from choking off the remote lake settlements in case of the fall of Quebec. But even after the establishment of Detroit, the interior of Michigan was virtually untouched. It was prime hunting ground for the furs being supplied by several Indian tribes, a supply the French did not wish to hinder. And the French, in general, did not colonize like the land-hungry British and, eventually, Americans.

The British won control of the region after the French and Indian War in 1763, and the Americans claimed it from the British after the American Revolution. But still, the region remained mostly home to the Indians—Chippewa, Sauk, Fox, Wyandot, Ottawa, and many others. While tribes of Native Americans on the eastern seaboard had been forced from their homelands by the hundreds of thousands, those in Michigan still held their land, even though the maps of the white men showed it officially changing hands at least three times.

Populating Michigan

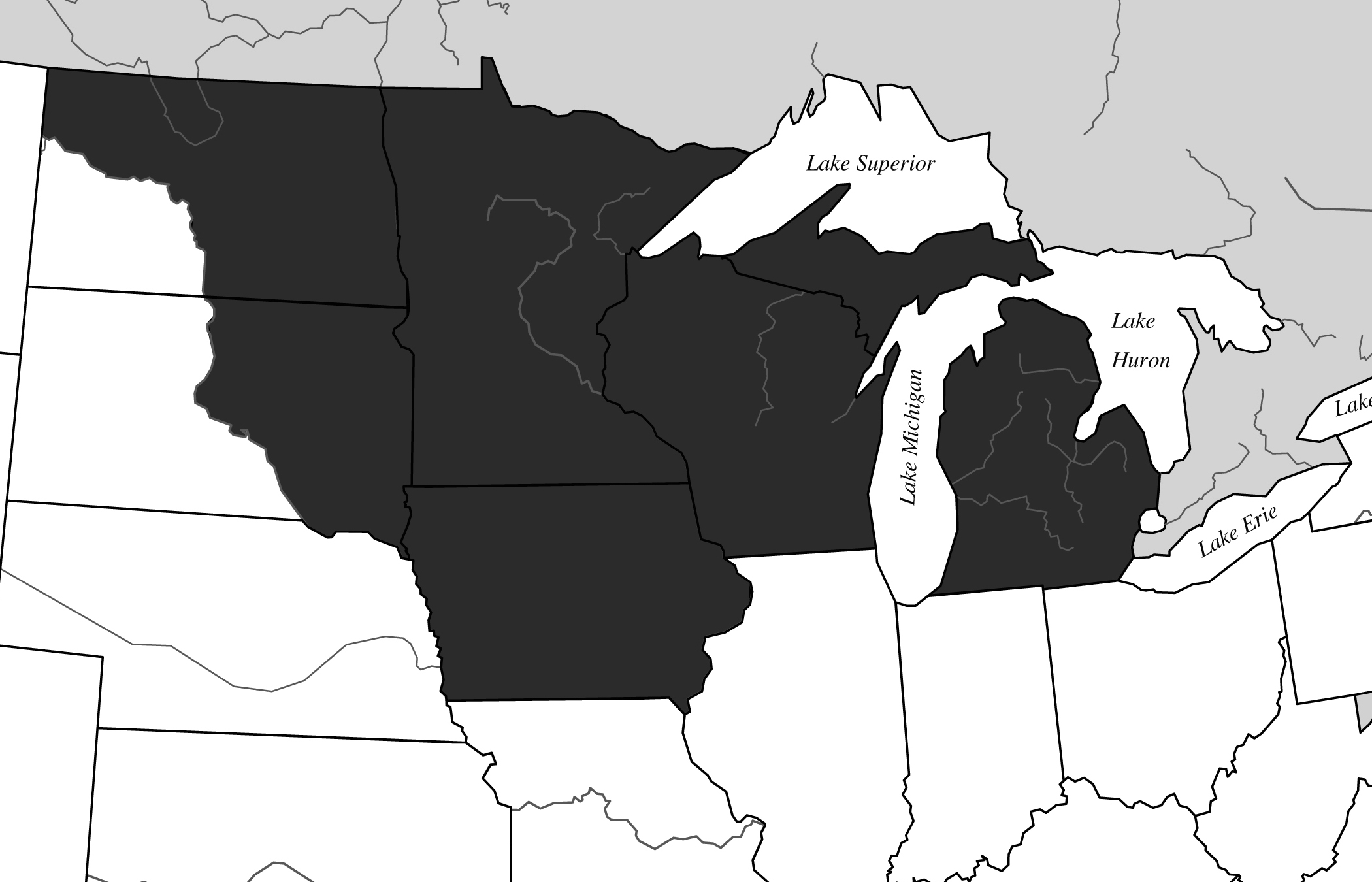

When the U.S. broke up the Northwest Territory the moniker “Michigan” was considered early on as a useful name for one of the new states, primarily because it was the name Europeans used for the lake that dominated the region. In fact, Thomas Jefferson had proposed “Michigania” to label a part of what is now Wisconsin. Instead, the Northwest Ordinance was adopted in 1784, providing for the division of the acquired lands into no more than five, and no less than three, new states. Michigan Territory was carved from the northwestern part of Indiana Territory in 1805, and it remained a territory until 1837, longer than any other in the Old Northwest. Initially Michigan included all of Wisconsin, and after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, her boundaries were extended to the Missouri River. The territory now included all of what are now Michigan, Minnesota and Iowa, and parts of the Dakotas.

Still sparsely settled, however, Michigan in the early 1800s was simply too remote and too inaccessible for Americans to flock to, especially when there was plenty of land (and plenty of “Indian trouble”) in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. But then in 1808 John Jacob Astor established his fur trading company, and Michigan was its primary supplier. And then came the Erie Canal.

extended all the way to the Missouri River

Hundreds of miles away from each other, New York and Michigan are connected by water—Lake Erie, to be precise. But the route from New York City, the state’s main seaport, and the lake was either circuitous or overland—either way it was slow. And so, between 1820 and 1825, New York State oversaw the completion of a 363-mile canal from the Hudson River just north of Albany to Lake Erie, which would provide an easy water route for settlers into the Great Lakes region and access to new markets for them to serve and be served by. By 1830 the white population of Michigan Territory was over 200,000—more than ten times that of pre-canal Michigan. The previously insulating waters surrounding Michigan’s peninsulas were now flooding her with people.

The U. P. And Toledo

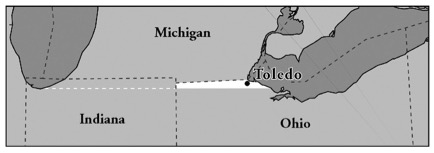

The reason that the Upper Peninsula is part of Michigan has partly to do with the city of Toledo, Ohio. By the provisions of the Northwest Ordinance, the city of Toledo (or more precisely, its location at the mouth of the Maumee River, a coveted water route) belonged to Michigan, whose border extended east from the southern-most tip of Lake Michigan. But when Ohio achieved statehood, it placed in its constitution a claim on the “Toledo Strip”—a tiny sliver of land created by moving the east end of Michigan’s southern border north about ten miles.

This border dispute, known as the “Toledo War,” raged for decades and hit its peak when Michigan was lobbying hard for statehood in 1835. As a way of compromising, Congress offered Michigan the Upper Peninsula in return for forfeiting its claim on the Toledo Strip. Michigan refused—the U.P. was considered a wasteland and no substitute for the thriving port city of Toledo. Finally, in 1837, Congress sweetened the pot, offering Michigan a share of a budget surplus of $400,000, to be distributed among all of the states. Territories were not eligible for the cash, so Michigan acquiesced on the Toledo Strip and begrudgingly took the U.P. and the money. Andrew Jackson made Michigan the 26th state on January 26, 1837.

End Notes

1. Snyder, Fred, “The Great Lakes - Still Great by Any Other Name,” Michigan Department of Environmental Quality , http://www.michigan.gov/deq/0,1607,7-135-3313_3677-15930--,00.html 3/4/03.

2. Catton, Bruce, Michigan: A Bicentennial History , (New York), p. 11.

3. Shankle, p. 73.