MARYLAND

Maryland, I’m coming home

—Vonda Shepard, Maryland

Don’t go back to Rockville

And waste another year

—REM, Don’t go back to Rockville

‘Tweener

Maryland benefits (or suffers, depending on your point of view) from its proximity to the nation’s capital. It is known for being one of two states out of which the District of Columbia is carved, but other than that distinction it is a state whose personality may be difficult to get a handle on. Its largest city, Baltimore, comes to mind, but many Americans can’t place it within the state’s boundaries—“It’s somewhere in Maryland” is about all people can usually tell you. After some thought, one might come up with some Maryland associations such as “the Naval Academy at Annapolis,” or “the Preakness Stakes at Pimlico Racetracks,” but even people who are familiar with their Civil War history might question whether Maryland fought on the side of the Union or the Confederacy.

Maryland is a ‘tweener. It is smack in the middle of the eastern seaboard, and while it sided with the Union during the Civil War, its citizens were passionately divided on the issue, and Maryland had regiments fighting for both sides. (African-American abolitionists Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass were both born in small Maryland towns.) It claims over 4,000 miles of coastline, but most of that is along the Chesapeake Bay and its islands; less than half of its shores actually abut the Atlantic Ocean. And while it is generally thought of as a “small” state, that too, is deceiving. It is bigger than New Jersey but smaller than Maine. You could say it is the biggest of the small states or the smallest of the mid-sized ones.

land mass than New Jersey

Yet still, this large small state is very diverse. Maryland’s highest point is Backbone Mountain at 3,360 feet, and its lowest point is Bloody Point Hole, falling 174 feet below sea level. The highest temperature ever reached in Maryland was 109ºF (July 1936) and the lowest trickled in at a chilly -40ºF (January 1912), yet Marylanders enjoy a relatively temperate climate most of the time. And when it comes to sports, most Americans might think of baseball great Babe Ruth or the Baltimore Orioles, or the pro football team, the Baltimore Ravens, but the state sport is actually jousting; heroes clad in armor, weilding lances, and waving brightly colored banners atop galloping steeds. The medieval tournament has been popular in Maryland for the past 300 years!

George Calvert

Maryland was the undisputed brainchild of George Calvert, a wealthy English courtier in the 1620s whose life was changed dramatically by his conversion to Catholicism in 1625. Calvert had been a favorite of King James I, receiving a knighthood in 1617 and later serving as the king’s principal secretary of state. As a member of Parliament Calvert suffered a crisis of conscience when in 1625 that body debated the persecution of Catholics, a religion he had recently espoused. He resigned his seat in Parliament, as well as his secretaryship, but was retained in the King’s Privy Council. King James also awarded Calvert an Irish Barony, making him Lord Baltimore of Baltimore, in County Longford, Ireland.

First Lord of Baltimore

Calvert’s interest in colonizing abroad built up for some years. Before his retirement, he served as a member of the London Company, which financed and orchestrated the founding of Jamestown, and as a member of the East India Company, he oversaw British interests in the Far East. In 1620 he initiated his first attempt at colonization in the New World with the purchase of a plantation at Newfoundland. After retiring, Lord Baltimore took his family to the settlement—which he had named Avalon—but after a brutal 1628-29 winter, he determined that he might prefer to begin a colony somewhere a bit warmer and not so vulnerable to French war ships.

The Catholic Connection

Besides wanting to change the location of his colony, Lord Baltimore’s motivations for wanting to colonize also changed. No longer simply a financial venture, Calvert now wanted to establish a refuge for persecuted Catholics and for anyone, for that matter, who was fleeing religious persecution.

King James died in 1625, so in 1632 it was from his son, King Charles I, that Calvert requested a new charter for land further south in Virginia. The King was prepared to grant him this land, which would have encompassed the southern portion of present-day Virginia and northern section of North Carolina. Jamestown residents, however, strongly objected to the establishment of a Catholic haven in such close proximity and voiced their objections rather assertively, so Calvert changed his request to a section of Virginia north of the Potomac River. Apparently King James’ esteem for Lord Baltimore had transferred from father to son, and King Charles signed a charter which was written primarily in Calvert’s own hand, “leaving only a blank therein for the name of the proposed province.”1

Lord Baltimore preferred the name “Crescentia,” after a Catholic martyr but deferred to His Majesty:

“The King, before he signed the charter, put the question to his lordship, what he should call it, who replied that he desired to have it called something in honor of His Majesty’s name, but that he was deprived of that happiness, there being already land in those parts called Carolina. ‘Let us, therefore,’ exclaimed the King, ‘give it a name in honor of the Queen. What think you of Mariana?’ Upon Lord Baltimore’s recalling the fact that a Jesuit by that name had written against the monarchy, the King proposed Terra Mariae [Mary Land], which was concluded on and inserted in the bill.”2

The Jesuit who had “written against the monarchy” was Juan Mariana of Spain who in 1598 published a defense of tyrannicide. He argued, among other things, that it was appropriate for a person to assassinate a king who imposed taxes without the consent of his subjects. After the fatal stabbing of King Henry IV of France in 1610, Mariana’s arguments were used as a defense of the assassination. King Henry IV was the father of Charles’ bride, Henrietta Maria. It certainly would not do to “honor” the queen by naming the colony after a defender of her father’s assassin.

An Appropriate Choice

Maryland, then, was named for King Charles I’s wife, Queen Consort Henrietta Maria of France. Besides being the daughter of King Henry IV of France and Marie de Medici, she was the younger sister of France’s King Louis XIII. She married King Charles very shortly after his ascent to the throne, when she was only fifteen years old. One of the many controversial aspects of Charles’ reign was his wife’s Catholicism and her refusal, just like Lord Baltimore, to reject her faith.

The beginning of their marriage was strained and stormy. Charles attempted to exert an awkward control over the young Queen, and she, headstrong and emotional, refused to be controlled. In one instance, Charles sent all of Henrietta Maria’s French servants back to France, replacing them with English ones. The young Queen, heartbroken and fiercely defiant, let loose with a tantrum at the end of which she knocked out a window with her bare fists.

After a few tumultuous years, though, the King and his Queen grew to genuinely love each other and together had nine children. Henrietta Maria would eventually attempt to aide her husband in his fight against the Parliamentary forces during the English Civil War, a war which Charles himself was busily provoking by doing things like marrying a Catholic princess and granting prime American real estate to a devout Catholic whose expressed intent was to create a Catholic refuge.

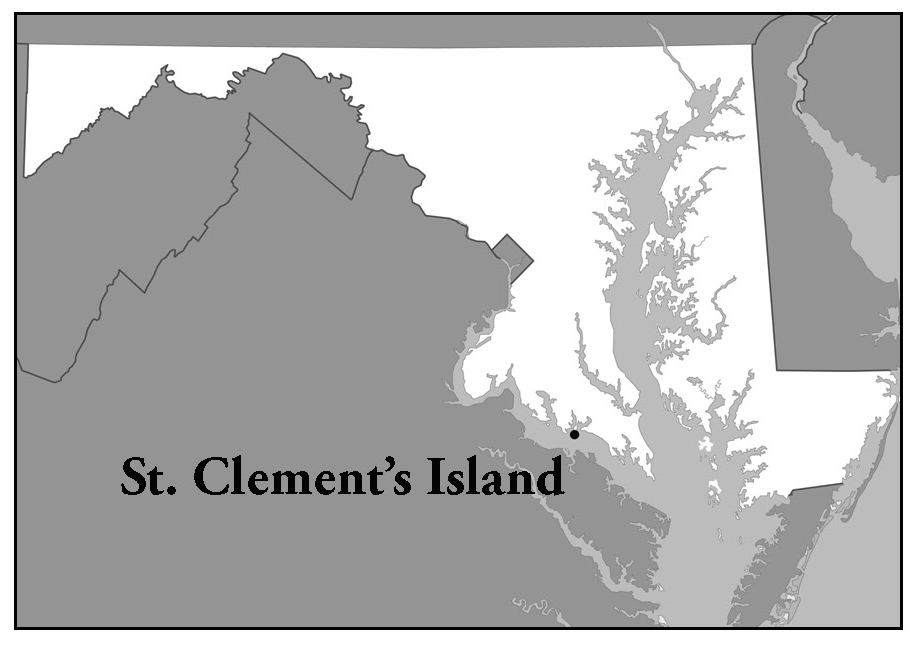

The Palatinate

George Calvert died in June of 1632, only a few days after his conversation with King Charles regarding a name for his new colony. It was left, then, to his son Cecilius, or Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, to receive the charter and build the new province. The first charter of Maryland was therefore issued in Cecil’s name, and he is the one who sent two ships, the Ark and the Dove , with their cargo of about two hundred colonists and provisions, to begin the colonization of Maryland. The ships arrived at St. Clement’s Island on March 25, 1634, and the passengers promptly held Mass to thank God for their safe arrival. March 25th is still celebrated in the state as “Maryland Day.”

From its inception Maryland was a “palatinate,” which is to say it was governed by a proprietor—Cecil Calvert until 1675—who had quasi-royal authority. The word “palatine” is derived from Roman times and described a palace guard. In English history, it came to describe a feudal lord who exercised sovereign power over his lands. Lord Baltimore answered only to the King of England and had the power to make laws and grant land however he chose; thus his control was nearly absolute.

Through the end of the seventeenth century, the colony endured a series of power struggles that mimicked those taking place in England between the Puritans of Parliament and the Royalists, who were loyal to the king. When the Parliamentary forces defeated and executed King Charles I in January of 1649, the proprietorship of Maryland was overthrown by Puritans. Then, in 1660, when King Charles II was restored to the throne of England, Cecil Calvert once again regained control of his palatinate. Calvert’s descendants maintained the palatinate until the “Maryland Revolution” of 1689, when Puritans once again took over the government of the colony. But the palatinate was restored one final time when, in 1715 Charles Calvert took the helm as the last Calvert to rule Maryland.

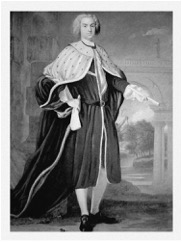

Fifth Lord Baltimore

Mason-Dixon Line

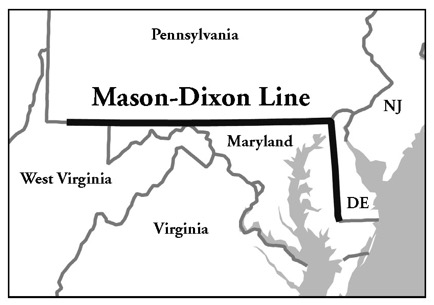

It was Charles Calvert, the fifth Lord Baltimore, whose reign oversaw the shrinking borders of Maryland. Like virtually everywhere else in the Colonies, Maryland was embroiled in border disputes on every front but none more pronounced—nor more famous—than the one with Pennsylvania and the three sons of William Penn, Jr. This dispute, which Baltimore ultimately lost, was the impetus for some of the most famous and the most creative surveying in America.

The “Mason-Dixon Line” is commonly thought of as the border between North and South, or between Free and Slave states, during the Civil War, but the actual Mason-Dixon Line is the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania. Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, two English astronomers and mathematicians, were hired to determine the location of the boundary between the two colonies, and they did so between 1763 and 1767. They placed stone markers at every mile and larger stones at every fifth mile. On the north side of the stones, they laid the arms of the Penns and on the south, that of the Calverts. They also cut down trees, creating a swath divided in half by the border line. This demarcation effectively ended the famous border war between the two families less than a decade before their proprietorships became inconsequential because of the American Revolution.

Maryland was the seventh state to ratify the U.S. Constitution, which it did on April 28, 1788. Some time later (an exact date is difficult to determine, though one would have to guess mid- to late-twentieth century), the term “Delmarva” was coined to describe the peninsula Maryland shares with Delaware and Virginia, Maryland consuming the bulk of it.

Delmarva. It’s an interesting coinage that compactly reduces to one word the symbolism and sentiment conveyed in the names of an English lord and two English queens.

End Notes

1. Andrews, Matthew Page, History of Maryland: Province and State , (Hatboro, 1965), p. 11.

2. Andrews, p. 11.