KENTUCKY

Kentucky Rain

Keeps fallin’ down…

—Elvis Presley, Kentucky Rain

Kentucky woman

If she get to know you

She goin’ to own you

—Neil Diamond, Kentucky Woman

From the Kentucky coal mines…

—Janis Joplin (Kris Kristofferson),

Me and Bobby McGee

Chickens and Horses

In the 1950s Colonel Harland Sanders labeled what would become one of the best kept secret recipes in culinary history with the name of the state in which he developed it. To this day the word Kentucky is likely to call to mind pressure cooked, finger-lickin’-good fried chicken, made with eleven celebrated (albeit secret) herbs and spices, and the white-coated, white-haired honorary colonel whose likeness appears on every box and bucket of it. In the twenty-first century it is conceivable that more people in the world (KFC® is franchised in more than fifty countries) know the taste of Kentucky Fried Chicken than could find the state of Kentucky on a map.

Kentucky is also famous for its blue grass, its bourbon, and its family feuds. Bourbon is the term coined for an American-made, distilled spirit that originated in Bourbon County, Kentucky, in the 18th Century. Jim Beam, Knob Creek, Maker’s Mark, and Wild Turkey are all Kentucky-born whiskies, dominating the bourbon industry and served at virtually every bar across the country.

The “Hatfields and McCoys,” the real-life warring Kentucky families of the 1800s, have become names symbolic of clan warfare everywhere. Simple family clashes between the two erupted into years of property conflicts, love betrayals, and murder. Dozens of family members on each side fell victim to the slaughter, eventually requiring state governors and militia to intervene before a truce was made in 1891, eighteen years after the first dispute.

And even people who don’t know an Andalusian from a Thoroughbred know of the Kentucky Derby, perhaps the most famous horse race in the world. The “Run for the Roses” is held every year on the first Saturday in May at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky. Few sporting events can compare with its tradition and ceremony, not to mention its brevity—the main event lasting no more than three minutes. The first Kentucky Derby was held in 1875, when only 37 of the 50 United States had yet been formed.

Americans know Kentucky as the “Daniel Boone state,” the place where arguably the nation’s most famous frontiersman hunted and explored. Indeed, mental pictures of coonskin caps and powder horns leap to mind at the mention of the state’s name, as well as images of the Shawnee Indians, Boone’s lifetime adversaries. And thanks largely to the efforts of Boone and his ilk and their efforts to open up the region to settlers, Kentucky would become the first of the trans-montane states to enter the union after the American Revolution.

An “Indian” Word

Kentucky, often written “Kentucke” in the early days of exploration, is a state whose name origins are shrouded in mystery and controversy. It is clearly derived from a Native American word, but which tribe’s language produced it is a matter of speculation. Consider…

Benjamin and Barbara Shearer’s book State Names, Seals, Flags and Symbols claims “The name Kentucky, the Wyandot word for ‘plain,’...was first recorded in 1753.”

In Kentucky Bluegrass Country , R. Gerald Avey says “...the original meaning of...the Cherokee term...‘Kentucky’ was ‘great meadowland’...”

In the forward of that same book however, Thomas D. Clark, a revered Kentucky historian, writes “the Iroquois gave it the name Kentucky , or Land of Tomorrow.”

Older histories simply call it an “Indian” word and leave it at that. More recent scholars acknowledge that the exact meaning and derivation of the word is not known, and they might point out that many of the languages spoken by tribes in Kentucky, including the three mentioned above, had Iroquois roots . The general consensus, however, seems to be that the word belonged to one of the dominant native tribes of the region and was used to refer to the area south of the Ohio River.

There is a commonly circulated theory that claims the name “Kentucky” means “dark and bloody ground,” but this speculation has been proven false. The myth probably emerged after years of bloodshed between and among Indian tribes, and eventually Europeans as well, over the Kentucky hunting grounds. One Kentucky history book reasons:

That legend probably came from remarks made by Cherokee chiefs Dragging Canoe and Oconostota at Sycamore Shoals when Richard Henderson bought what rights the Cherokee had to a large part of Kentucky. “There is a dark cloud over that Country,” Dragging Canoe reportedly warned, and Oconostota said to Daniel Boone as they parted, “Brother, we have given you a fine land, but I believe you will have much trouble settling it.”1

This region may never have been settled by a single group of natives even before European encroachment, at least not for long—a fact that no doubt has generated some of the confusion regarding its name.

Due to the lush woods, gently rolling hills and valleys, and numerous streams and rivers, Kentucky thrived as a deer and beaver habitat. This richness of the land made it a desirable commodity, and its hunting rights were bitterly fought over by the Cherokee, Iroquois, Shawnee, and other Indian tribes. During the mid 1700s, with the impeding American explorers on their bountiful land, these tribes quickly became frustrated at the existence of yet another competitor for the land and its fruits. Yet the Americans’ intentions were more commanding than those of the natives in that they not only competed for the guaranteed economic gain, they ultimately intended to settle the land—they wanted to live in Kentucky, to own it.

A County in Western Virginia

To colonists in the early eighteenth century, “Kentucky” was a vague region in Western Virginia on the opposite side of the forbidding Appalachian Mountains. It was only known to them through the reports of early explorers, hunters, and missionaries as well as by word of the local Indians with whom they traded. Daniel Boone, who began exploring Kentucky in the late 1760s is of course the most famous of these early white adventurers, but there were many others both before and after. They brought back tales of acre upon acre of green pastures, rivers packed with fish, and fur-bearing animals of every kind. Though this area was uninhabited by whites, they regaled their listeners and readers with accounts of menacing Indian tribes who harassed them during their ventures. Ironically, it was these same natives whose name for this coveted land became widely used by the English and other Europeans.

Technically, to the Virginians, the region was part of their vast Orange County formed in 1734 out of unexplored western lands that extended northward to the Great Lakes and westward to the Mississippi River. It was named for William IV, Prince of Orange. In 1738 the county was divided, the western portion becoming Augusta County, named for Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gothe, wife of Frederick, Prince of Wales. Their eldest son would become King George III, whose reign would so famously nudge the American colonists toward revolution.

It was in fact King George III who in 1763 made the trans-montane region of Virginia off-limits. By that year the Cumberland Gap, named by Dr. Thomas Walker in 1750 after the Duke of Cumberland, had been established as the easiest path through the mountains, and settlers had begun to trickle westward. In order to buy time to develop a western policy, King George issued a proclamation prohibiting settlement west of the crest of the Appalachians and ordering any of his subjects residing there to move east immediately. Virginians were outraged because they wanted to use the land to pay their soldiers for service in the recently-won French and Indian War. Their anger was somewhat mitigated after hearing of the horrors of Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763-65), a brutal and bloody series of battles and massacres between an Indian alliance led by Ottawa Chief Pontiac and British soldiers and settlers in the Ohio River Valley. The war somewhat justified the position of the crown.

In 1770 Augusta County was further divided, and the western portion containing Kentucky became Botetourt County, named for a well-liked governor of Virginia. Two years later, the western lands were once again lopped off and named Fincastle County, either for John Murray, Earl of Dunmore and Viscount of Fincastle, or for his son, Lord Fincastle. Then, in 1776 Fincastle County was broken up once again for ease of administration. The name Fincastle was discarded (possibly because Lord Dunmore was now an unpopular British Military leader in Virginia trying to squash the rebellion), and three new counties were formed: Montgomery, Washington, and Kentucky County, whose northern, southern and eastern boundaries were those we know today as the state. Only the western tip of the state, the land west of the Tennessee River was not part of Kentucky County.

Separation

In 1779 the population of Kentucky County began to change dramatically. Following the war, the government was responsible for paying the mercenaries who had bravely fought its battles. Land ownership was offered to soldiers as payment, and it was not long before they began to move west to claim it. Other settlers, no longer hindered by the British king’s proclamation, also poured through the Cumberland Gap by the thousands, so that by 1800 the population of the County was over 200,000.

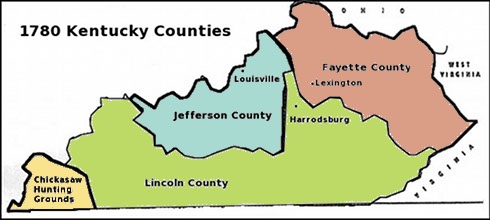

From the time of its first discovery by colonists, Kentucky was a separate entity from Virginia, partly because of the physical barrier—the Appalachians—that divided them, and partly due to mindset. Virginia was the first British colony, and it was accustomed to being divided. Its northern and southern boundaries had changed drastically since the establishment of Jamestown, when “Virginia” referred virtually to the entire eastern seaboard. By the time the county of Kentucky was formed, it was clear that the western border would change as well to accomodate a new entity in whatever form Kentucky was destined to take. For example, when in 1780 Kentucky County was divided further into three separate counties—Fayette, Jefferson, and Lincoln—they were still referred to collectively as Kentucky.

The handwriting on the wall became even clearer in 1783 when the former county was formed into the District of Kentucky, which now made it more administratively independent, and further divided it from Virginia. It had its own court system, but still sent a delegation to the Virginia legislature. But Kentucky also had its own political agenda which was vastly different than that of the easterners. Among its unique problems were the obvious and continuing Indian hostilities, and the politics of navigation on the Mississippi River. Residents were frustrated when these problems were all but ignored by the Virginia, and later the federal, governments.

On December 27, 1784, each militia company in the District of Kentucky sent a representative to the town of Danville for a convention. The only topic on the agenda was the issue of separation from Virginia. There would be nine more conventions over the next ten years as Kentuckians, Virginians, and the federal government debated the matter. There was no precedent yet for adding states to the original thirteen—Vermont would not become the fourteenth state until April of 1791, only a year ahead of Kentucky. However, it wasn’t as if the new American government wasn’t thinking about the process. The Northwest Ordinance started as a resolution that Congress passed in 1780 to deal with the Northwest Territory. It provided for the lands acquired from the British after the Revolution to “...be settled and formed into distinct Republican states.”

Spanish Kentucky?

Some Kentuckians, however, had different ideas. A movement led by James Wilkinson, a brigadier general during the Revolution, would have delivered a newly separated Kentucky to Spanish control. Wilkinson lived a notorious life of intrigue, and his motives in the Kentucky endeavor were largely those of personal financial gain. It was eventually learned that he was treasonously conspiring with the Spanish in New Orleans to bribe leaders of the Kentucky statehood movement to instead form an alliance with Spain against the U.S. (In later years he would involve Aaron Burr in a scheme which would forever brand the former Vice President as a traitor.) Wilkinson also enticed businessmen of Kentucky to consider his strategy by obtaining trade concessions from Spain, which controlled the Mississippi River. These concessions provided a badly needed outlet for exports from the area and brought to Wilkinson enormous personal profit.

In 1788, when the U.S. once again failed to give Kentucky statehood status, many in the region became increasingly frustrated with the fledgling feds and more enamored of Wilkinson’s plan. Serious proposals at the convention in November of that year proposed that Kentucky draft a constitution, declare itself separate from Virginia, and offer the federal government an ultimatum: either accept Kentucky as a separate state, or we will go elsewhere.2 The proposal failed, however, largely because the Spanish were losing interest, and the Kentuckians no longer had the leverage of a Spain-backed secession. So the District of Kentucky plodded on toward statehood.

Statehood and borders

Finally, on February 4, 1791 Congress passed a bill that would admit Kentucky to the union. State leaders set to work drafting a constitution and selecting representatives, and on June 1, 1792 Kentucky entered the Union as the fifteenth state.

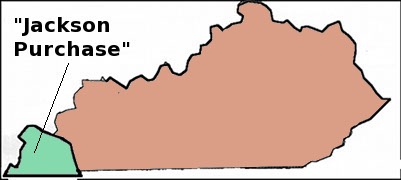

Bordering seven other states, Kentucky found itself embroiled in border disputes that would simmer at varying intensities until as late as 1890. In 1818, however, Andrew Jackson and Isaac Shelby facilitated what would become the most drastic change in Kentucky’s borders. Approximately two thousand square miles of land west of the Tennessee River was purchased from the Chickasaw Indians for three hundred thousand dollars, and formed into what is now the western tip of Kentucky. This region is bounded by the Mississippi, Ohio, and Tennessee rivers (the Tennessee was dammed at this point in 1944 to form Kentucky Lake) as well as the state’s southern border with Tennessee—some twelve miles south of the rest of the state’s border with Tennessee. This section of the state is still referred to today as the “Jackson Purchase.”

End Notes

1. Harrison, Lowell H. and James C. Klotter, A New History of Kentucky (The University of Kentucky Press, 1997).

2. Harrison and Klotter, p. 60.l.