KANSAS

“Toto, I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore.”

—Judy Garland as Dorothy

from The Wizard of Oz

Carry on my wayward son

There’ll be peace when you are done

—Kansas, Carry On My Wayward Son

I’m as corny as Kansas in August…

—

I’m In Love With a Wonderful Guy

from

South Pacific

The Middle

It is a symbol of normalcy, of everything that is familiar to us, everything recognizable as home. We think of Judy Garland as Dorothy with her freckles, pigtails, and checkered dress. We think of rolling fields of wheat, long, straight, dirt farm roads, windmills, county fairs, hard work, and lots of silence. Even city folk find something down right homey about Kansas .

Our image of Kansas is not exactly exciting. Even the major cities of the state—Wichita and Topeka (Kansas City is, of course, mostly in Missouri)—evoke calm. Kansas seems like a place that restless young teenagers want to get out of, and only after experiencing the treacherous world outside her borders can they recognize the beauty and comfort of what they left behind. To some, everything outside of Kansas probably seems like Oz.

Except for an edge along a tiny section of the Missouri River, Kansas’ borders are a set of four straight lines that proudly surround the geographic middle of the forty-eight contiguous states. That is, of course, another way of saying that people in Kansas (those restless, young teenagers perhaps) who want to leave the United States have to book a longer flight than people who live in any other state.

Apparent political inconsistency is another hallmark of Kansas—as in What’s the Matter With...? Thomas Frank wrote his bestselling book after the 2000 presidential election about people who vote against their own self interests—as thousands in Kansas had just done. In the introduction he wrote, “People getting their fundamental interests wrong is what American political life is all about.” Not all of course, but according to Frank many of those “people” are Kansans.

There is, of course, another image of Kansas that comes to us from the Wizard of Oz . It is the foil to that image of utter normalcy that the state conveys: tornadoes . Kansas lies in the heart of “tornado alley,” a vaguely defined section of the country where twisters are most common. The Fujita scale measures tornado intensity, category 5 tornadoes classified as the most powerful of the lot. Kansas lands are terrorized by this most severe level of twisters more than any other state in the country. A large section of central Kansas is one of the highest risk areas for tornadoes in the U.S., though an even larger section of her southern neighbor, Oklahoma, shares that distinction. Alabama and Mississippi also have stretches of very-high tornado risk, as do big chunks of Arkansas, Nebraska, and Texas. Nevertheless, when we think of tornadoes, we’re more likely to think of Kansas than any other state. Thanks perhaps to Dorothy, Toto, and the gang.

Kansas-Nebraska Act

The creation of Kansas was intricately entangled with the creation of Nebraska, and their formations marked a turning point in the nation’s political destiny. After Missouri achieved statehood in 1821 it quickly became clear that white settlers coveted the land west of the Missouri River. That land that was now designated “Indian Territory” and several reservations had already been established to accommodate eastern tribes who had migrated or been “removed” westward.

In 1845 John O’Sullivan, a writer and editor of a New York newspaper, codified the concept of “Manifest Destiny,” writing that, “In its magnificent domain of space and time, the nation of many nations is destined to manifest to mankind the excellence of divine principles.” The United States embraced this concept as justification for expanding its borders westward, and so the organization into territories of the land west of Missouri quickly became a foregone conclusion for most Americans.

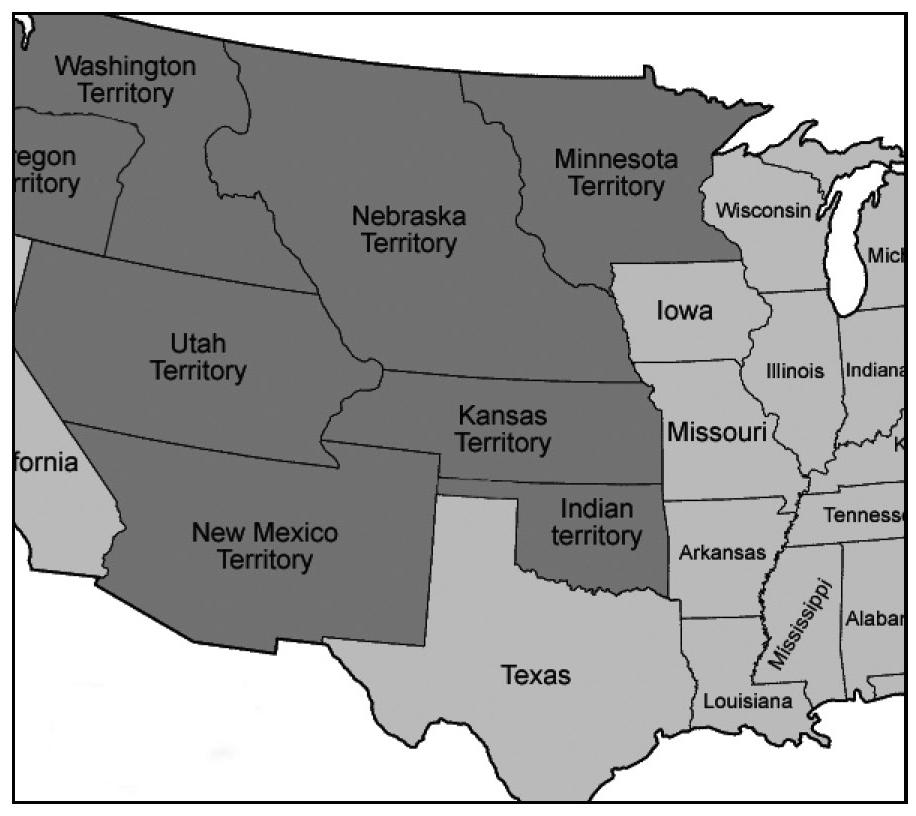

By 1853 several attempts had been made to organize the Territory of Nebraska, but all had failed due in large part to the political controversy surrounding slavery. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 designated 36º 30’ north latitude—the southern boundary of Missouri—as the line north of which slavery would not be legal. The proposed new territory of Nebraska fell north of this line. Southerners had already "allowed" California to enter the Union without slavery, but they were hell-bent on blocking the creation of any more “free soil.”

Stephen Douglas, famous future debater of Abraham Lincoln, took up the cause of Nebraska, but he was pushed and prodded by a senator from Missouri named David Rice Atchison. Atchison was an advocate for the southern states and a staunch supporter of slavery. The Nebraska bill became a way for slave states to push for the repeal of the Missouri Compromise and institute “ squatter sovereignty ,” or as it is more commonly known “popular sovereignty,” whereby any new state, regardless of its relation to the 36º 30’ line, would be allowed to determine its own status with regard to slavery. Missouri, a slave state, would probably supply most of the settlers to the new territory, and if popular sovereignty were established, those settlers would be able to vote in slavery. The most vocal opposition to the repeal of the Missouri Compromise came from Iowans, many of whom had moved north from Missouri specifically to avoid paying taxes in a slave state. Iowa, too, expected to supply settlers to any new territory west of the Missouri River, and these settlers would be “free soilers.”

It was Atchison who proposed that the Nebraska Territory be divided, the northern section to be Nebraska and the southern to be Kansas. In this way he could appease the Iowans, virtually giving them their own free state to settle, and still achieve his main objective, which was the repeal of the Missouri Compromise and the continued use of slave labor.

Atchison proposed the name Kansas to Douglas, taking it from a prominent river in the region. He is said to have claimed that since Nebraska was named after a river, so Kansas should be too. The name was, of course, already in use by the time Atchison proposed it. The city that grew up on the Missouri River at the mouth of the Kansas had been called Westport on the west side of the Missouri, but the ferry landing on the east (Missouri) side came to be known as “Kansas Landing,” “Port of Kansas,” and eventually City of Kansas . Residents of the town generally referred to it only as Kansas , and it was becoming a thriving gateway to points west. David Atchison’s suggestion of the name was probably influenced by the prominence of this town near what would be the new territory. Once the territory was created, the port city officially changed its name to Kansas City to distinguish it from the territory. The eastern border of Kansas however, would remain the Missouri River, so the city that lent its name to the state would remain outside the borders of that state.

State of Kaw?

The name that David Rice Atchison proposed for the territory was, as stated, taken from the river. The river, like so many others that had been mapped by Europeans, was named after a prominent tribe living along its banks. Kansas, it turns out, is the English plural of Kansa or Kanza , a Siouan tribe that lived along the Kansas River at the time of their first meeting with Europeans. The name for the tribe had been spelled many (by some accounts more than a hundred) different ways on maps and in journals from as early as the 1673 expedition of Marquette and Joliet or possibly even earlier. Some believe that the references to the Escansaques or Escanzaques by members of a Spanish expedition led by Juan de Oñate in 1601 to locate the village of Quivira were actually the Kansa Indians.

The Kansas belonged to the Dhegiha Sioux group of tribes, a linguistic group that also included the Omaha, Osage, Quapaw (Arkansas), and Ponca tribes. At one time these five tribes were one and migrated westward before contact with Europeans, but from where has never been determined. Some say they could have moved from as far east as the Atlantic seaboard, but more prominent theories suggest a region near Lake Michigan. Sometime before 1673 (the year Marquette and Joliet ventured down the Mississippi), the Dhegiha Sioux divided and separated. Ironically, there is evidence that as late as 1698 the Kansa tribe was still living east of the Mississippi River and may have been driven westward by other tribes during the domino effect that European immigration had on virtually all of the Natives in North America. Had it not been for the push of the Europeans, the “Kansas” River might today be in Illinois.

The 1970s rock band Kansas , in tribute to their namesake, released a song called “People of the South Wind,” acknowledging the widely held belief that the word “Kansas” means “wind people” or “people of the south wind.” Ethnologists have noted that other Siouan tribes also contain a “Kansa” or “Kauza” division, a reflection of a certain clan’s status within the tribe. While there is strong ethnological support for the interpretation of “Kansas” as “people of the south wind,” there are those who support other theories. Kansa interpreter Addison W. Stubbs, writing in 1896, suggests that the word closest to “Kansa” in the tribe’s own language was konza which meant “plum.” He stressed, however, that the name “Kansa” was, to the members of the tribe, simply what other people called them and had no particular meaning.1

According to Kansas place-name scholar John Rydjord, the Kansa Indians used the word Hútañga to refer to themselves, a name which may be related to the Siouan word Hu-tam-ya, meaning “by the edge of the shore.”2 The name Kansa , used by other Siouan tribes who repeated it to early French explorers, was probably pronounced “Kauza” or “Konza.”

There is strong sentiment within the state for the name “Kaw” instead of “Kansas” when describing both the river and the tribe. This shortened appellation is a by-product of the French tendency to abbreviate place names on maps. Historian John Francis McDermott writes

The Kansas River for the French was the Kan, and even today people speak of that stream as the “Kaw” (sometimes “Caw”), which was as close to the French pronunciation as the Americans could get.3

In fact, the modern tribe maintains its identity as the “Kaw Nation” based in Kaw City, Oklahoma, and while the river still appears on maps as the “Kansas,” it is also affectionately referred to, particularly by locals, as the Kaw. It does not appear, however, that anyone has ever suggested applying that name to the state.

Bleeding Kansas

Ultimately, David Rice Atchison’s plan to divide Kansas from Nebraska worked, and the bill to create Nebraska now became the Kansas-Nebraska Act, historically better known as a significant step on the nation’s road to Civil War rather than an effort that simply organized two territories and set them on the path to statehood.

Kansas was also set on the path to grisly bloodshed. “Bleeding Kansas” is the graphic term used to describe the territory during the period in the 1850’s in which residents of Kansas were supposed to be deciding their own position on slavery. As promised, people moved west from Missouri and Iowa, as well as from places further north and further south, many of them with no intention of settling but hoping only to sway elections. Kansas became a tinderbox.

Among those who moved west were the sons and other followers of the Puritan abolitionist, John Brown, followed shortly by Brown himself, and they were among the first anti-slavery warriors to “fight back” against the encroaching pro-slavery contingent. The close proximity of so many violent advocates on both sides of the slavery issue touched off a series of massacres and battles that became a portent for the gruesome, desperate war that lay in the nation’s future.

The western border of the Territory of Kansas originally extended all the way to the crest of the Rocky Mountains, and there were many in the region who wanted not only to keep that boundary but to annex part of Nebraska Territory, making the Platte River the northern boundary of Kansas. The Colorado gold rush of 1859 was the major factor in moving Kansas’ western border east to 102 degrees longitude, making room for the new Territory of Colorado . Strong efforts to include the Platte River country in Kansas eventually failed.

When, in early 1861, seven states had already seceded from the Union and four others were threatening to do so, the U.S. Congress saw its chance. Now acting as the legitimate government of the United States, but without the southern states to obstruct them, they granted statehood to Kansas as a free state. President James Buchanan signed the Act on January 29th, 1861. This served, of course, to exacerbate the tensions between north and south, and four months later the nation was at war.

End Notes

1. Unrau, William E., The Kansa Indians: A History of the Wind People (Norman, 1971), p. 10.

2. Rydjord, John, Indians Place-Names (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968), p. 14.

3. John Francis McDermott, “The French Impress on Place Names in the Mississippi Valley,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society , vol. LXXII, No. 3, August 1979, p. 231.