IOWA

“Is this heaven?”

“No. It’s Iowa.”

— Field of Dreams

There’s nothing halfway

About the Iowa way to treat you

When we treat you

Which we may not do at all.

—Meredith Wilson from

The Music Man,“Iowa Stubborn”

Corn

Just as strong as next-door neighbor Wisconsin’s association with cheese is Iowa’s association with corn… corn-fed cattle, corn-fed chickens, and corn-fed strapping young men. The state’s name conjures up images of vast fields of cornstalks drenched in golden sunlight, Kevin Costner ambling through them, an invisible sage whispering in his ear, “If you build it, he will come.”

Generations of farming in America’s heartland has imbued the name Iowa with a certain wholesomeness. This aesthetic involves hard work, rising before dawn to milk cows and feed chickens, and perhaps squeeze in a little Bible study. One also imagines a cautious, provincial people, proud of their state and their way of life. The mind’s eye, of course, sees most of them in overalls, unless it happens to be Sunday.

These proud, independent people are also famous for their primary (pun intended) role in selecting our nation’s presidential candidates. Like the first pitch on opening day, the Iowa caucuses in January or February kick off election season every four years. The event creates front runners and forces resignations, largely deciding for the rest of the country the field of competitors for the White House. While important, this honor subjects the entire state to a barrage of political ads so intense that it is perhaps a privilege the rest of the states do not wish to wrest from the people of Iowa.

When one ponders possible vacation spots Iowa seldom tops the list. In fact it seems almost counter-intuitive for the state to have a tourism agency, but in fact they do, and their website is slick and professional. It introduces you to such state attractions as Living History Farms, the actual Field of Dreams, and the world’s largest motor home factory, as well as Iowa’s many not-so-wholesome casinos. Still, as a tourist destination Iowa has difficulty competing with the untouchable vacation industry of, say Hawaii.

Iowans, one suspects, don’t mind.

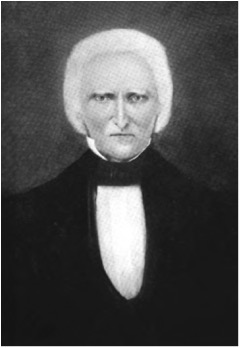

Albert M. Lea

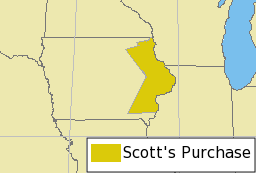

Albert M. Lea was a twenty-seven year-old lieutenant in the U.S. Army who, in 1835, led a company of dragoons (armed, mounted soldiers) to explore a tract of land on the west side of the Mississippi River that had been acquired three years earlier from the Sauk and Fox Indians. The region, part of the Wisconsin Territory, was commonly called Scott’s Purchase after General Winfield Scott, who had negotiated the treaty with the tribes. It was also sometimes called the Black-Hawk Purchase, an ironic name derived from the Sauk elder who, in 1832, led a rebellious band of tribe members into Illinois to attempt to reclaim their homeland.

As punishment for the Indians’ “insolence,” the United States dictated a treaty to several regional tribes which conferred upon the U.S. this strip of “purchase” land in return for about $600,000. The district was a small tract of land about thirty miles wide, bounded on the south by the state of Missouri, on the east by the Mississippi River, and by an angled line on the west, giving it the shape of a miniature mirror-image of California.

Lieutenant Lea preferred neither of the two commonly used names. He instead chose to refer to the land as the “Iowa District” after the river which “flows centrally through it, and gives character to most of it, the name of that stream being both euphonious and appropriate....” Upon his return, Lea wrote a short book describing the land in glowing terms: “The general appearance of the land is one of great beauty.” Of the white people who were already pouring into the district he wrote,

“The character of this population is such as is rarely to be found in our newly acquired territories. With very few exceptions there is not a more orderly, industrious, active, pains-taking population west of the Alleghenies than is this of the Iowa District.”

It seems even in 1835, Iowans were cultivating their wholesome reputation.

Lea titled his book Notes on The Wisconsin Territory; Particularly with Reference to the Iowa District, or Black Hawk Purchase , and a thousand copies were printed and sold. One hundred years later the book was reprinted, this time with a new title and an “Explanation” at the beginning. It was now called The Book that Gave Iowa its Name , an obviously tantalizing label for students of state name derivation. The “Explanation,” which appears as a preface or foreword, declares “While the information which [the book] records on the Iowa country in 1835 is invaluable to students of Iowa history, the supreme historical significance of Lieutenant Lea’s book is the fact that it fixed the name Iowa upon the country that was to become the Territory of Iowa in 1838 and the State of Iowa in 1846.”

Tribe, River, State

“Iowa” is an Indian word whose original meaning has been obscured over generations of language loss and corruption. It has, as a result, assumed an almost comical number of diverse definitions. Among them are “this is the place,” “beautiful land,” “crossing, or going over,” “gray snow,” “dusty noses,” “something to write with,” “one who speaks gibberish,” “drowsy ones,” “those who put to sleep,” “marrow,” “squash,” and “none such.”

Historians and scholars disagree at varying intensities about which definition is correct, some asserting confidently that one of the above meanings is true without mentioning the other possibilities. In 1955 Joseph P. Harrington, working for the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology, wrote “The Iowa form of the tribal name is ‘Ayuxwa,’ which means ‘one who puts to sleep.’” A Dakota-English dictionary written by Stephen R. Riggs in 1890 and reprinted in 1992 offers the following definition: “i-ó-wa, n. of owa; something to write or paint with, a pen or pencil.” Others, however, acknowledge the conflicting definitions and concede that the true meaning of the word will almost certainly never be known.

To further complicate matters, the Iowa Indians of the 17th and 18th centuries used a different word to describe themselves—Pahoches (the “h” is pronounced like the “ch” in the name of the German composer Bach.) This word was used by the Chiwere—a linguistic group that included the Missouri, Oto, and Iowa tribes—of the middle Mississippi, while “Iowa” was used by the Dakota Sioux of the upper Mississippi. But the meaning of the word “Pahoches” is just as unclear as that of “Iowa,” and the two may simply be synonyms from different dialects of Sioux. Mildred Mott Wedel, an ethnohistorian who compiled and published a synonymy of names for the Iowa tribe in 1978, conveys the exasperation of scholars in their endeavor to determine a true definition:

The variety of explanations proffered by the Ioway and other Indians to explain the Chiwere name to Americans makes it quite clear why linguists prefer to view with caution the descriptive meanings or folk etymologies of proper names.1

But while a meaning for “Iowa” may be elusive, the history of the word and its adoption as a state name is still traceable. In 1676 a French missionary, Father Louis Andre, wrote of a group of Indians who had come to his mission near what is now Green Bay, Wisconsin. These natives, he reported, were called “Aiaoua” and were visiting their friends and relatives among the Winnebagos who lived near the mission. Historians generally agree that Andre’s reference to this tribe is the very first written reference to the Iowa Indians by a European.

Andre, however, was receiving his information about the tribe second- or third-hand. It is believed that Algonquin-speaking Ottawa and Chippewa tribes, those close to Father Andre, borrowed the Dakota name for the Iowas and probably conveyed that name to him. Had Andre been speaking to the Iowa or even the Winnebago Indians directly, he would likely have received the Chiwere name “Pahoches” to describe them.

There is overwhelming evidence that the original (i.e. correct) pronunciation of the word was “Ioway.” Indeed, the final “y” was used in the spelling of the tribe’s name in at least seven treaties with the U.S. government between 1824 and 1854.2 According to Wedel, the Spanish were responsible for changing the pronunciation of the final syllable from “way” to “wah.” They spelled the name “Ayoa,” “Aiaoas,” and “Hayuas” during their reign over western Louisiana in the late 1700s. Wedel also explains that anthropologists “have found it useful to use ‘Ioway’ to distinguish the Indian name from that of the state.” She acknowledges, however, that in 1938 the tribe adopted the spelling “Iowa” to match the orthography of the state name.3

As early as 1685 the French began to use the name of the Iowa Indians to label the river upon which they lived. Throughout the following centuries the region surrounding the river would be claimed by all three major European powers and eventually the United States. The spelling would change, but the river continued to be named for the Iowa Indians.

In 1778 Thomas Hutchins, an accomplished cartographer as well as experienced frontiersman and Indian agent, mapped the region. His map is considered the first to use the modern spelling of the word Iowa (to name the Iowa River), and that map was used in 1803 by Thomas Jefferson and Merriwether Lewis to plan the route for the Corps of Discovery on Lewis and Clark’s trek across the North American continent.

Honey War and Slavery

In a familiar pattern, the river of the region took the name of the tribe, and the land, largely by virtue of Albert Lea’s little book, took the name of the river. On July 4, 1838 the region became the official U.S.Territory of Iowa.

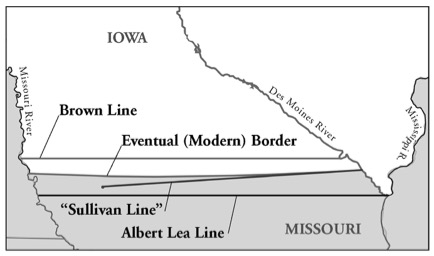

Iowa was part of the Louisiana Purchase area in 1804, and remained a part of the Louisiana Territory until 1812 when Missouri was carved out and given territory status. In 1816 John C. Sullivan surveyed the northern border of Missouri Territory, defining that area that had been ceded to the United States by the Osage Indians. Sullivan made a minor error in his survey, however, causing the line to be slanted, and so in 1837 a new survey was undertaken by Joseph C. Brown. Brown, unfortunately made an even larger mistake, and designated a fourteen-mile strip in southern Iowa as part of Missouri.

1st Territorial Governor of Iowa

Upon taking office, Robert Lucas, Iowa’s first territorial governor, immediately had a border dispute on his hands. Lucas was no stranger to border wars, having served as Ohio’s governor during the Toledo War between Ohio and Michigan, which came dangerously close to armed combat (see Michigan). Most disturbing to the Iowans who now found themselves residents of Missouri was that Missouri had entered the Union as a slave state. Many of the people in the disputed region had moved there specifically to avoid paying taxes in a state that supported slavery. If the new boundary held up, they would be forced to move again as a matter of conscience.4

President Martin Van Buren selected none other than Albert M. Lea to mediate the controversy. (Ironically, the disputed region was considered by Iowans to be part of their Van Buren County.) Lea studied the situation and submitted four proposals to Congress, each representing a different border configuration. But while Congress debated, some impatient Missouri militiamen angered Iowans by storming north and cutting down three trees which were rich in honeycomb, prized by Iowa farmers as a source of valuable sugar. Tensions mounted, but fortunately in the end, the trees were the only casualties of what came to be known as the “Honey War.” But the dispute would not be finally settled until 1849, three years after Iowa became a state. In that year the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the original “Sullivan line,” straightened out except for a tiny notch in the northeast corner, would be Iowa’s official southern boundary.

In a complicated set of circumstances, the bill providing for Iowa to create a constitution (the final step toward statehood) changed her borders dramatically, moving the western border from the Missouri River eastward to a longitude that nearly sliced the state in half. Iowans were outraged and refused to act on their own statehood until their original borders were restored. Stephen Douglas of Illinois proposed the compromise that was eventually accepted, moving the western border back to the Missouri River, and placing the northern border at the 43° 30’ parallel, instead of following the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers further north. Boundaries now firmly in place, President James K. Polk signed Iowa into existence as the 29th state in the Union on August 4, 1846.

End Notes

1.Wedel, Mildred Mott, “A Synonymy of Names for the Ioway Indians,” Journal of the Iowa Archeological Society, vol. 25, 1978, p. 54.

2.Wedel, p. 60.

3.Wedel, p. 60.

4.Wall, Joseph Frazier, Iowa: A Bicentennial History (New York, 1978), p. 32.