INDIANA

“Indiana Jones! I always knew some day you’d come walking back through my door.”

—Karen Allen as Marion

from

Raiders of the Lost Ark

Gary, Indiana,

Gary, Indiana,

Gary, Indiana

Let me say it once again.

—Meredith Wilson,

Gary Indiana

from

The Music Man

Letterman and Hoosiers

Late night television addicts think of David Letterman at the mention of the name Indiana. They might wonder if the city of Indianapolis has gotten around to naming I-465, the highway that loops the city, “David Letterman Highway.” They may also wonder how the Ball State Cardinals football team is faring this year. But for others, perhaps those who watch The Tonight Show, the easternmost of the three “I” states that define the American Midwest is the Hoosier state, the farm belt, basketball, and for those of a certain age and disposition, the whole embarrassing episode with Bobby Knight.

And then of course, there’s Harrison Ford, Notre Dame, the Indianapolis 500, and a quaint little song from The Music Man about Gary, Indiana, that will stick in your brain like It’s a Small World at Disneyland. For some, there is also the image of a young Dennis Quaid and his band of teenaged malcontents, swimming in the quarry and riding their bikes triumphantly in the 1979 award-winning movie Breaking Away .

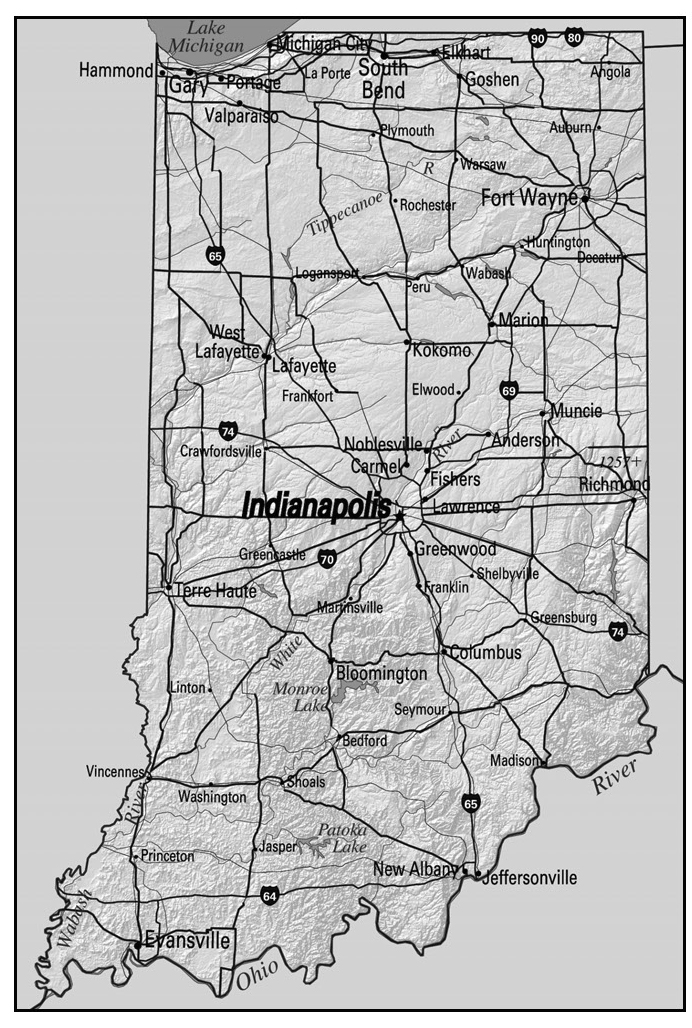

A glance at a road map of Indiana can remind you of Rome—as in, “all roads lead to it,” though in this case the roads lead to Indianapolis. Such a glimpse fills you with a comforting sense of pragmatism—the state capital in the geographical middle of the state and sharing its name so intimately, with all of the major highways radiating out from it like a star.

A closer look at that map however, can reveal something that many non-midwesterners would never have considered a possibility. Indiana has a shore! A coast! Okay, it’s not on an ocean, but still...how can a state in the heart of the Midwest have a beach? It’s supposed to be land-locked and full of wheat or corn or something. And yet, there it is: Marquette Beach on Lake Michigan in Gary, Indiana. Hmm. Perhaps Mr. Letterman would prefer a beach to a highway.

Well, Obviously...

The derivation of the name “Indiana” seems so obvious that in searching for it, one tends to find a lot of phrases like “It simply means...” or “It is obviously derived from...” or “Clearly....” It makes sense to assume that the word “Indiana” is directly derived from the word “India” or “Indian,” and so it is. These brief assertions are then inevitably followed by a long, detailed description of the possible derivations of the word “Hoosier,” Indiana’s perennial mascot.

In naming the states of the Northwest Territory, the fashion of using native or aboriginal names was just beginning, and the use of the feminine Latin ending was still in vogue. Whether “Indian” can be considered aboriginal is certainly debatable, but in the minds of early 19th century legislators, the area being organized was closely associated with natives, and their word for native was “Indian.” Slap on the Latin ending, and you get “Indiana.”

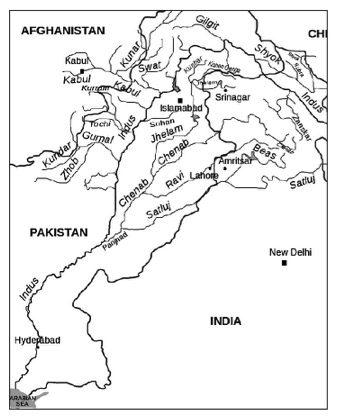

What is not really quite so obvious is that the word India , and therefore Indiana , takes its original derivation from the Sanskrit word sindhu meaning “a river.” As early as 893 A.D. King Alfred the Great referred to the area in modern-day Pakistan of the “Indus” river and called its inhabitants Indikoi . Eventually the word made its way into Greek and then Latin, and by the time of Columbus’ voyages, had become “India,” “the Indias” or “the Indies” and was commonly used to refer to all of Southeast Asia. Interestingly, the Indus river headwaters wind through the disputed territory of Kashmir and into China. None of the Indus River flows through what we today call India.

It is also generally acknowledged that the application of the word “India” to the West Indies in 1492 was a mistake, applied by Columbus in the false assumption that he had landed somewhere in southeast Asia. In the journal for his first voyage he writes about the place he named “Indies” and its inhabitants who he dubbed the “Indians.” Thoroughly debunked is the theory that the word “Indian,” as Columbus used it, was originally “El Gente in Dios” or “People of God.”

Even after Europeans determined once and for all that what Columbus had found was not the Far East but a New World, the names Indies and Indians stuck. These misnomers so quickly and so thoroughly propagated that for Americans today the word “Indian” is more readily associated with Native Americans than with people from India. Also, we tend to use “Indian” as a noun (he is an Indian) when speaking of Native Americans and as an adjective (he is Indian) when speaking of people from India.

It has been pointed out that while Columbus believed he had found India, he was actually looking specifically for “the noble island of Cipangu,” which is to say, Japan. Had he believed himself successful in his quest, the Native Americans we now call Indians might have a different, if still inaccurate, name…and so might Indiana. Cipangana ?

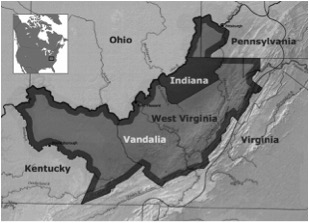

The First Indiana

The “first Indiana” was actually in West Virginia and is, in fact, sometimes referred to as the “first West Virginia.” It was a tract of land procured by a group of Virginia and Pennsylvania land speculators who called themselves The Indiana Company. The leader of the group was Samuel Wharton, son of a successful Philadelphia merchant and friend of Benjamin Franklin.

These men came together with a common complaint—that they had lost valuable property in New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia during the French and Indian War. They wanted the help of Parliament in reclaiming their losses, but Parliament, noting that the losses were accrued during a declared war, refused, and the petitioners became known as the “suffering traders.”

Ever persistent, the “sufferers” formed The Indiana Company, the creation of which is poorly documented. The name may have derived from the intention of the Company to negotiate directly with the Indians in an attempt to acquire land west of the Alleghany Mountains, land which was off limits by order of King George III’s proclamation of 1763. At a meeting at Fort Stanwix, New York, in 1768 the suffering traders gained cessions from the Six Iroquois Nations for a section of land between the Ohio and Monongahela Rivers in what is now West Virginia. They called the land Indiana after their company.

Once Indiana was secured, Samuel Wharton and a smaller group of speculators attempted to gain control of a much larger tract of land. They proposed a new colony called either “Pittsylvania” after William Pitt, the English parliamentary reformist, or more likely “Vandalia” for the Germanic tribe of Vandals from whence Queen Charlotte was believed to have descended. Vandalia would have completely surrounded Indiana and consumed most of what is now West Virginia, but Wharton and others engaged in coercive machinations that proved ruinous to the whole venture, and many of the speculators eventually declared bankruptcy. With the Declaration of Independence, the new states vigorously asserted their land claims west of the mountains, only to surrender them willingly to the new Federal Government, and so “Indiana” was effectively liquidated.

The Second Indiana

The name “Indiana” is said to be (clearly, obviously, simply...) a Latin version of “place of Indians.” Given that “Indian” was already a Latin version of “Indus,” this seems a bit redundant. Still, Latinizing words, that is to say, applying a Latin ending (usually a feminine suffix) to the word for use as a place name, was certainly en vogue during the founding and naming of the nation—Virginia, Louisiana, Montana, America, etc.

Once the Indiana Company was finished with the name “Indiana,” it was no longer applied to a place or a group of people. But it was out there, in the consciousness of the new Americans and their government, and it had a particular meaning. While “Indiana” may today signify David Letterman or fields of corn, in the late eighteenth century it still meant Indians. It was probably only a matter of time before the name got applied to a region that was strongly associated with Native Americans, which was virtually any section of the continent that was not yet dominated by white people.

The Northwest Territory was claimed by the United States after the Revolution, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 (see Ohio) made provisions for the division of the region but placed no names upon the lands. Ohio Country and Illinois Country had already long been referred to as such, one for the river which dominated the area and the other for the Natives who inhabited the banks of the upper portion of the Mississippi River. But the section in between the two was nameless.

When the Northwest Territory began to be divided in earnest, the first bill to address the process drew a line dividing the region into two sections, and naming the eastern section “Washington” and the western section “North-Western Territory.” This bill passed the House of Representatives, but the Senate committee that debated the bill didn’t care for the names. They removed the name “Washington” and began referring to what is now Ohio as the “Territory North-west of the River Ohio,” and they inserted the name “Indiana” for the region in the west.

The name must have made perfect sense to the committee members. Since the end of the Revolution, the U.S., while outwardly claiming to have won the Northwest Territory by conquest over both the British and the Indians, also spent much time and effort acquiring concessions from, and signing treaties with, various Indian tribes who had inhabited the land, perhaps for centuries. After years of negotiation and broken treaties, many native tribes were angered by the usurpation of their lands by the Americans, and they continued to harass settlers and enrage U.S. officials. For the new American government, this was the beginning of a century of handling the “Indian Problem" (usually in brutal fashion). It would play out over and over again, east to west, north to south, for decades.

In 1805 Indiana’s northern border was fixed to create the new territory of Michigan, and four years later, the Territory of Illinois was formed to the west. With no further discussion of a name, Indiana was approved by President James Madison as the nineteenth state of the Union on December 11, 1816.

Despite its name, Indiana today has one of the smallest Indian populations in the country, with fewer than 13,000 people claiming that heritage in the 2000 census. The Midwest in general does not have, nor is it even perceived to have, a concentrated population of Native Americans. This legacy of European domination in the 19th century was perhaps not foreseen by those who placed the named “Indiana.” It seems that one subject that tends not to be inspired by the name “Indiana”...is the subject of Indians.