ILLINOIS

Just got home from Illinois

lock the front door, oh boy!

—Creedence Clearwater Revival

Lookin’ Out My Backdoor

I drank musty ale at the Illinois Athletic Club with the millionaire manufacturer of Green River butter one night

—Carl Sandburg, Chicago Poems

“Holy Cow!”

—Harry Caray

The I’s Have It

Illinois is one of the “I” states—those three that line up in a crooked midwestern row providing a nice alliterative device for young students of geography to learn their names. Illinois is the long one in the middle, flanked by Iowa to the west and Indiana to the east. Too bad they’re not lined up alphabetically.

Illinois is perhaps best known for its largest city. “City of the Big Shoulders,” “The Windy City,” “My Kind of Town,” Chicago is a favorite setting for movies and prime-time television dramas. It conveys images of the wind blowing off of Lake Michigan into Wrigley Field, of Al Capone, the Mayors Daley, the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the Sears Tower, ER , and of course...Michael Jordan and Sammy Sosa.

Oh, and there is one other celebrity commonly associated with Chicago, someone who captured the nation’s political imagination in the first decade of the 21st century, someone who was swept into the White House in a stunning 2008 presidential election that saw the rise of the first African-American to be elected to that high office. I write, of course, of Michelle Obama, the 44th First Lady of the United States, who was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. But that’s Chicago.

Illinois is in the Midwest, and the Midwest means farms. A large majority of the state is covered in farmland—massive fields of corn owned by wholesome families who drive tractors and wear overalls. That is, of course, the image, but modernization of the agricultural industry has tweaked what once might have been this reality—to say the least. The family farm has been bought up by ADM at foreclosure auctions and the corn fields converted to bioengineered soybeans. The wholesome families more likely work as systems analysts, wear Cubs jerseys and drive Hondas. But the mythical family farm is still the embodiment of the Midwest in the minds of many Americans, even if our mental images admittedly lag a few years—or perhaps decades or centuries—behind reality.

So which Illinois is Illinois—Chicago or the Midwest? Both, of course. They are at once inseparable and irreconcilable. Call it schizophrenia, or call it what the Illinois tourism industry calls it...a cross-section of American culture.

Lincoln

Illinois maintains a strong affiliation with Abraham Lincoln. The state calls itself the “Land of Lincoln,” and for all the states that considered that always-a-bridesmaid name Illinois probably has the most legitimate claim. It was in Illinois where Lincoln served in the legislature and where he debated Stephen Douglas in his losing bid for senator. He was living in Illinois when he won the presidency in 1860.

But it is widely acknowledged that Lincoln was not born in the state of Illinois. In fact, he could not have been because Illinois was not yet a state on February 12, 1809 when Lincoln was born in Hardin County, Kentucky. Illinois wasn’t even a territory yet. On the day of Lincoln’s birth, it was the western section of Indiana Territory, its white settlers begging Congress for governmental organization: “...we have been neglected as an abandoned people, to encounter all the difficulties that are always attendant upon anarchy and confusion.”1

On March 9, 1809, about three weeks after Abraham Lincoln’s arrival into the world, the Illinois Territory, by an act of Congress, also arrived.

The French

By that time the name “Illinois” had been used to describe the region—along the Mississippi River, mostly on the east side, north of the Ozark Mountains—for over a century. It was coined by the French, who knew of the Illini Indians as early as 1640. As the French began to push westward from the St. Lawrence River into the Great Lakes region, they became interested in reports of a large tribe of Algonquin-speaking people living not too far to the west along a mighty river. They wrote the name “Eriniouai,” “Irinions,” “Aliniouek,” and eventually “Illiniwek.”

The first contact between the French and the Illini came in 1666 in what is now Iowa. A map produced in 1667 by Jesuit priests Dablon and Allouez named Lake Michigan “Lac des Ilinois (sic).” In 1673 Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet, the first a missionary and the other an adventurer, explored the Mississippi southward from Lake Michigan further than any European had yet traveled. They took Illini men with them as guides and translators, and also as subjects of study, learning that the term “Illini” referred to several loosely organized bands—the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Cahokia, Michigamea, among others—who lived along the banks of the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers.

A decade later, in 1683, Rene Robert Sieur de La Salle would travel the Mississippi and claim the entire river basin and all its tributaries for France, calling it “Louisiana” for his king (see Louisiana). Because their motivation was primarily trade with the natives and religious conversion of the natives, the French commonly—more so at least than the English and Spanish—applied native names to the lands they claimed, adjusting aboriginal words to suit their own phonetics. The word “Illini” was that tribe’s name for itself, and was made plural by adding “-ek” to the end. “Illiniwek” meant simply “the men” or “the people,” but French writers chose to replace the “-ek” ending with the French suffix “-ois,” giving us “Illinois,” and that oh-so-French silent “s.” The French suffix made the word descriptive and is often likened to the English suffix “-ese” as in “Chinese.”

But the pronunciation of the word “Illinois” has never been entirely straightforward. A paper published in 2000 by linguist and place-name scholar Allen Walker Read studies the historic variations on the spoken version of the word. Read describes the inclination by Englishmen in the late 19th century to attempt to apply proper French by pronouncing the word “Illin-wah.” He discusses the long and continuing competition between the pronunciations “Illinoy” and “Illi-noise” and sites historic variations on spelling that include “Illinoyes,” “Illinese,” and even “Ylinnesses.”2

Illinois Country

Illinois to the French was not a county or a district in the 1700s. To them the name described the people more than the land, and so “Illinois Country” was the borderless region one passed through when traveling along the Mississippi from New France to New Orleans, a critical route for French traders. The Illiniwek strongly associated themselves with the French. They traded with them, guided them, and fought with them against both Indian and European enemies. But while the French claimed the Illinois country, they did little to settle it, except to allow their missionaries to engage the Indians and to set up just enough outposts (including St. Louis) to maintain a relatively high profile along the river, giving notice to England and Spain of their claim.

The French claim was not, however, completely unchallenged. The English colony of Virginia, whose charter bestowed upon her a limitless western border, also claimed Illinois Country. But since the French and not the English had control of the Mississippi River, it was not until 1738 that Virginia took official measures to assert that claim. In that year the Virginia assembly created Augusta County, bordered on the east by the Allegheny Mountains and on the west and north by “the utmost limits of Virginia.” This was the colony’s way of saying that they didn’t know precisely what the western border was, but they would keep claiming land until they hit an ocean.

Of course, claiming the land and governing the people in it were two different things. The French had a few settlements in Illinois, but in 1738 the English were just beginning to creep over the Alleghany Mountains into Kentucky. It would be decades before there would be enough English colonists in Illinois to warrant any official government. Illinois Country began to be referred to by Virginians as the District of West Augusta, differentiated from the County of Augusta, which had an actual governable population.

As English colonists began to move westward, the county names they applied were often geographically meaningless. They usually used names of royalty whose favor was being courted and rarely anything that described the land being named (Augusta was named for the Saxe-Gothe Princess Augusta, married to Prince Frederick, Eldest son of King George II). But “Illinois Country” meant something, though it didn’t necessarily refer to the Illini Indians. To the English “Illinois Country” meant French outposts, the Mississippi River, and the frontier of English territory.

After the Seven Years War, or “French and Indian War” as it was known in America, The Paris Treaty of 1763 gave to the English the eastern half of Louisiana from France, and Virginia’s claim to the region became internationally recognized. Among the recruitment efforts for settlers to come to “Illinois Country” was a pamphlet that was circulated in Edinburgh, Scotland, proposing the colonization of Illinois country. The specific boundaries would have included the current states of Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan, and the proposed name was “Charlotiana, in honor of Her Majesty, our present most excellent Queen.”3 Settlers moved in quickly, but instead of encouraging efforts to colonize the region, King George III, Charlotte’s husband, in order not to inflame already tense dealings with the western native tribes (what a concept!), issued a proclamation that the region was off limits to colonial settlement, a decree that exacerbated the tensions between colonists and the crown, and eventually helped lead to the American Revolution.

The Americans

During the Revolution few people saw any military or strategic issues in the remote Illinois Country. One exception was George Rogers Clark, a Kentucky frontiersman (his little brother William would years later accompany Meriwether Lewis at the head of the expedition to explore the American Northwest). Clark feared for the few American settlements in the Ohio Country, Illinois Country, and Kentucky which were vulnerable to Indian attacks—attacks that were encouraged, and even led by, the British. In 1778 Clark led bold but relatively bloodless movements against British forts at Vincennes, Kaskaskia and Cahokia, in the heart of Illinois Country. By convincing the mostly French settlers there to join in the revolution against the British, he secured the region for the Americans, drove out the minimal British troops, and reduced the threat of Indian attacks, as the Illiniwek still tended to follow the lead of their French neighbors.

The Virginia Assembly, learning of Clark’s victories, wasted no time in reasserting their claim to the conquered region. Illinois County was created on December 9, 1778 from the region of Augusta County on the west side of the Ohio River. Perhaps because the county was created so quickly, the borders of the new Illinois County were vague, and the name was not debated. They simply used the name that they had used for decades, the one supplied by the natives, and altered by the French.

In 1784, after the war ended, Virginia ceded all of her claims to the Ohio Country, including the county of Illinois, to the federal government. The Feds, in turn, developed the Northwest Ordinance (see Ohio) for the purpose of disposing of the Northwest Territory, of which Illinois comprised the southwestern edge. In 1800 Ohio was separated from the rest of the region and given its own territorial status. The remainder of what had been the Northwest Territory was renamed Indiana Territory, and it included “Illinois Country.”

But the people of Illinois wanted a separate territorial government and knew that the Northwest Ordinance mandated one. In their impatience to divide themselves from Indiana, the subject of a name was again not debated. Just as Virginia had used the traditional name for their region, so did the settlers, and on March 9, 1809, the Illinois Territory was formed.

Don’t Forget Chicago

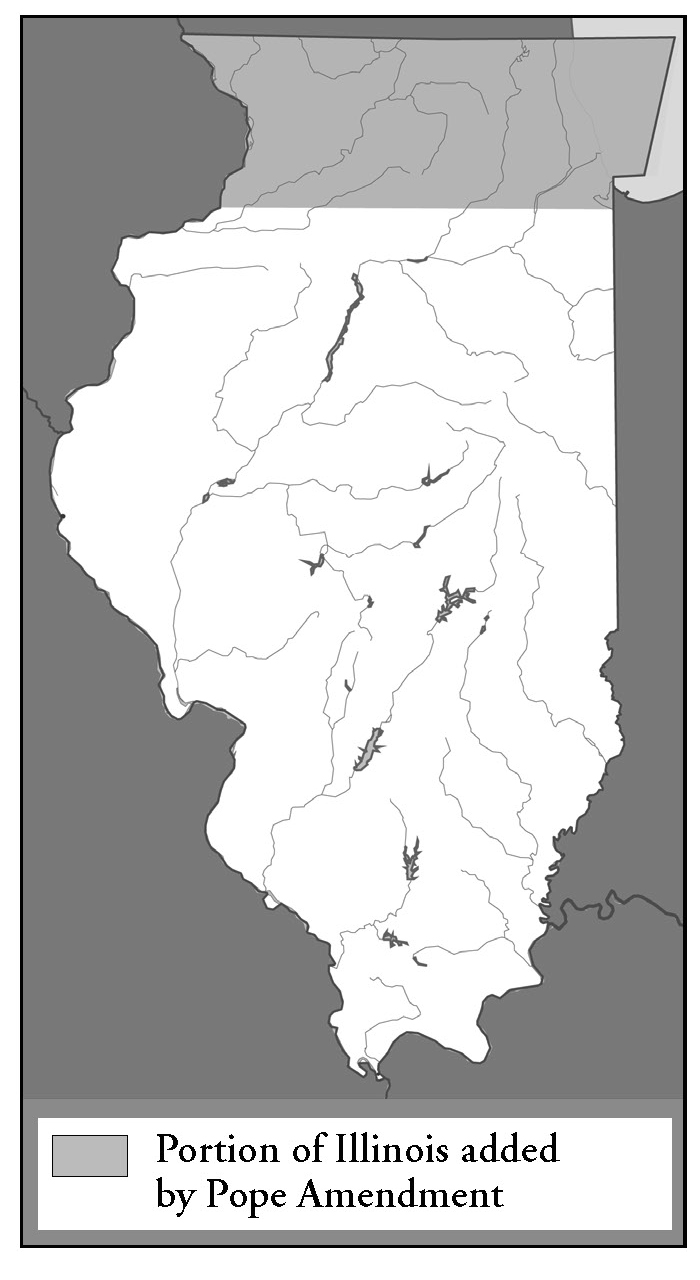

The Northwest Ordinance did not contain a name for the territories it proposed, but it did suggest borders, and those borders were largely adopted when Illinois became a territory. But in 1817, when the residents began to petition for statehood, the territorial representative, Nathaniel Pope, noticed a problem. Pope was the nephew of Daniel Pope Cook (after whom Cook County is named), and he had for two years been lobbying hard to make Illinois a state. Nathaniel Pope proposed an amendment to the enabling act for Illinois that would move its northern border north by about forty miles. The amendment was accepted. Had he not made this proposal, Illinois would have no shoreline on Lake Michigan and would have no clear water route to the East Coast via the Great Lakes. Eight thousand square miles of what is today Illinois, and which currently contains about sixty percent of the state’s population—including Chicago and all its suburbs—would have become part of Wisconsin.

Very shortly after the acceptance of the enabling act, Illinois drew up its constitution which was quickly passed by the U.S. Congress. On December 3, 1818, President James Monroe signed the act that created the twenty-first state of the Union: Illinois.

End Notes

1. Carrier, Lois A., Illinois: Crossroads of a Continent (Chicago, 1993) p.33.

2. Read, Allen Walker, “The Pronunciation of Illinois,” Place Names in the Midwestern United States, Edward Callary, ed., Studies in Onomastics, No. 1. , (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2000), pp. 81-96.

3. Alden, George Henry, “New Governments West of the Alleghanies Before 1780,” Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin, Historical Series , Vol. 2, No. 1, p. 12.