IDAHO

You know, you’re gonna have to face it

You’re addicted to spuds.

—Weird Al Yankovic, Addicted to Spuds

You’re living in your own Private Idaho

—The B-52’s, Private Idaho

An Unusual State of Mind

“The name Idaho induces an unusual state of mind,” writes one state historian, who goes on to describe how the word “conjures up visions of openness and vastness, with continually recurring manifestations of nature’s versatility.”1 Okay, yeah, and POTATOES.

No matter how genuine the natural versatility and vast beauty of Idaho is, people hear the state’s name and think of a big, brown Russet Burbank potato or perhaps a long, hot MacDonald’s French fry.

Idaho’s association with potatoes is well deserved. The state accounts for over a third of all potatoes grown in the United States each year and lends its name to the most dominant frozen potato products company on the planet—Ore-Ida Foods, Inc. The state’s leading agricultural industry was begun by a community of Mormon settlers who moved north from Salt Lake City in 1860 and believed themselves to still be within the borders of Utah. By 1876 these industrious farmers, who by this time were clearly and unapologetically within Idaho Territory, were shipping millions of pounds of potatoes to mining camps all over the west. The region maintained its spud dominance, and to this day Idaho symbolizes the potato industry.

The other strong association with the name Idaho is perhaps an unfortunate one. Besides Boise, one of the most recognizable Idaho place names is Ruby Ridge, a tiny, secluded homestead in the northern mountains. The 1992 confrontation there between the FBI and the reclusive family of Randy Weaver—which led to the shooting deaths of one FBI agent as well as Weaver’s wife Vickie, and their 14-year-old son Sam—thrust into the national spotlight a relatively new aspect of Idaho’s reputation. It turns out that one of the last regions of the United States to be penetrated and settled by whites has become a haven for white-supremacist groups, often survivalist and paramilitaristic in nature. Idaho is now known worldwide as the U.S. state with a disproportionate population of reclusives ranging from those mildly skeptical of government to extremists who are often belligerently racist and paranoid.

Some people, when they think of Idaho, think first of its odd shape. One historian calls it a “geographical monstrosity,” while another quotes Idaho Statesman editor John Corlett: “When the great planners in Washington finally got through breaking things up, they left us with a crazy patchwork of a state.” While more than half the state is south of Montana, Idaho has a short (about forty-four mile) border with Canada, shorter even than that of Vermont. The state’s northeastern border follows the crest of the Bitterroot Mountains, which appear on the map to consume all but a southern sliver of Idaho. It sort of makes you wonder where they find enough farmland to grow all those potatoes.

Bitterroots

In 1805, Lewis and Clark named the Bitterroot Mountains after a small, pink flower, the bitter roots of which were boiled and eaten by local natives. After crossing those mountains into what is now Idaho, the Corps of Discovery passed from the region of the Louisiana Purchase into land which was not only nameless but mysterious. It was one of a dwindling number of areas on Earth that remained unexplored and unmapped by white men, though the U.S., Spain and England all laid claim to it.

Great Britain, who held perhaps the strongest international claim, labeled the land “Nova Albion” or “New Albion”— Albion being an ancient Roman name for England—based on maps and journals from Sir Francis Drake’s 1577 voyage. Lewis and Clark would soon learn that British explorers traded occasionally from their ships with the natives on the Pacific coast, but had not ventured inland. Spain considered the region part of California, but the Spanish missions on the Pacific Coast extended only as far north as San Francisco Bay, and the days of Spanish exploration and colonization were waning fast. One of the driving reasons for the Lewis and Clark expedition was to lay firm U.S. claim to the enigmatic land that today we casually refer to as the “Pacific Northwest.”

The Bitterroot Mountains, the most formidable obstacle faced by the Corps of Discovery, are the historical homeland of the Nez Percé Indians, so named by the French who erroneously believed that tribal members traditionally pierced their noses. Beginning with their contact with Lewis and Clark, the Nez Percé continued for several decades to have peaceful relations with the governments of the U.S. and Great Britain, those two nations having agreed in 1818 to joint occupation of what was becoming more commonly known as “Oregon Country.” Of course, “occupation” may be an overstatement, as the craggy, towering mountains of the Idaho panhandle remained intimidating to most white travelers and settlers.

But that intimidation would not last. By the mid-1800s, trappers and loggers discovered the rich resources of those forbidding mountains and found ways to harvest them. While the white population remained sparse, it became clear to the natives as well as to the government that more and more settlers would begin to discover the natural wealth of the region.

In 1846 the Oregon Treaty officially divided the Oregon Country between Britain and the U.S., extending the U.S./Canada border along the 49th parallel all the way to the Pacific, the U.S. taking the southern section, and Britain the north. Almost immediately the U.S. government began pursuing treaties with the Nez Percé Indians and other tribes of the region to purchase most of the land. When Oregon Territory was created by Congress in 1848 it included the current states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. In 1855 the Nez Percé were encouraged to move with other regional tribes to the Umatilla reservation to the southwest, but the tribe indicated that they wished to remain in their ancestral homeland. The Territorial governor agreed to “let” them stay in return for their surrender of about 13 million acres.

By this time in 1860, Mormon settlers began to build communities in what is now southeastern Idaho. Still, the northern, mountainous section of the territory remained the domain of the Nez Percé.

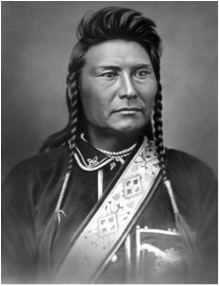

Chief Joseph

Gold was discovered in 1863 near the Wallowa Valley just across the Idaho border in Oregon. White miners began pouring into the region, sparking a dispute between the Nez Percé and the U.S. government. The valley, i.e. the gold, was undeniably within the limits of the Nez Percé reservation in a region considered among their most sacred. In 1870 the U.S. attempted to force the tribe to sign another treaty in which they would give up all but about a tenth of their reservation and leave them with a small fraction of their former homeland.

Tribal elders, who had for years worked amicably with the U.S. government, were outraged. One of these elders was Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, or Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain, who had changed his name to Joseph after converting to Christianity. He refused to sign the treaty ceding his homeland—his beloved valley of Wallowa—and he died in 1871, leaving his son, also named Joseph, to lead his people in the fight against the U.S. government. The 1877 war between the retreating Nez Percé and U.S. troops has gone down in history as a series of brilliant, yet ultimately unsuccessful, maneuvers by the Indians who were avoiding being herded onto their assigned Idaho lands. The defining moment in the saga came in Chief Joseph’s famous speech of surrender:

“Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever .”

Creating Idaho

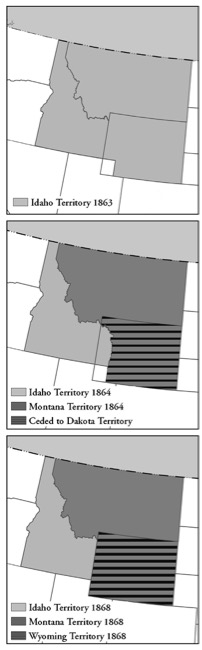

Idaho Territory was created in 1863 and initially included modern Idaho, Wyoming and Montana. Abraham Lincoln signed the Idaho Organic Act on March 4th of that year, but the story of the name for the new territory goes back even further, originating in what is now Colorado.

In 1859 the Pike’s Peak mining camps in the mountains of what would become Colorado held an election to name a delegate to press for their own territory status in Washington D.C. Initially the results indicated that a miner named George M. Willing had been chosen as representative, but after massive fraud was discovered in the balloting, Willing was replaced with B. D. Williams.

Even though he had lost the election, Willing—sometimes called “Doc” Willing due to his training as a physician—proceeded to Washington anyway. It is unclear what his relationship was with Williams, though some adversarial tensions must have existed between them, as Willing continued to represent himself as the “legally elected delegate to Congress from the territory of Jefferson,”2 Jefferson being the name the miners had chosen.

Nevertheless both men, along with a small contingent of supporters, began working for territorial organization, and in April of 1860, a bill was submitted to theHouse of Representatives for what would be called “Idaho” Territory. It was Williams who pressed for the name, but as will be shown, the suggestion for it came most likely from Willing. On January 30, 1861, the name was discussed in the Senate. Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon objected to “Idaho,” but the name was defended by James S. Green of Missouri.

“Idaho is a very good name,” said Green, “In the Indian language it signifies ‘Gem of the mountains’.”

Lane argued “I do not believe it is an Indian word. It is a corruption. No Indian tribe in this nation has that word, in my opinion...It is a corruption certainly, a counterfeit, and ought not to be adopted.”3

But the name was adopted. After Lane’s strenuous objections, however, Williams became suspicious and decided to investigate.

A few days later a presumably sheepish Williams asked Henry Wilson, a senator from Massachusetts and future U.S. Vice President, to have the senate bill amended—quickly—substituting “Colorado” for “Idaho.” Williams told him that he had discovered that “Idaho” was, in fact, a fraud, a made up word, that it did not mean “gem of the mountains,” nor did it mean anything at all. It was a complete fabrication perpetrated by Willing, the backstory to which would not come to light until 20 years later. Wilson was able to get the amendment passed, and the name was dutifully changed to “Colorado.”

The explanation for the frantic name change came to light in a letter written to the New York Daily Tribune on December 8, 1875. William O. Stoddard, a former aide to Abraham Lincoln and himself no stranger to practical jokes, “explained how his ‘eccentric friend,’ the late George M. Willing, had coined the name early in 1860. Willing (said Stoddard) often had told the story ‘with the most gleeful appreciation of the humor of the thing.’”4

So then why...?

So if everyone now knew that “Idaho” was a fabrication, why then was it used to name any state at all? The answer may lie in the all-important euphony of the name. Whether it was Willing or someone else who created the word, it was one that people immediately found pleasing. Even its fabricated definition was agreeable enough that it continued to be used even after its origins were discovered. In June of 1860, a steamboat which would provide service on the Columbia River was christened the “Idaho.” A small mining town in Colorado also took the name “Idaho Springs,” and to this day, that town’s Chamber of Commerce propagates the old “gem of the mountains” definition to explain the name.

By 1863 the new territory east of Washington and Oregon needed a name. It was a huge region, and a name that indicated its mountainous terrain would be appropriate. James M. Ashley, head of the Committee on Territories, proposed the name Montana, and the bill passed through the House of Representatives with that name. Ashley was bitterly disappointed when the Senate then amended the bill and replaced “Montana” with “Idaho.”

The source of the change is a bit surprising—it was proposed by Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson. Now, while there were no doubt members of Congress who had forgotten, or never knew of, the quick name change for Colorado after the name “Idaho” was found to be a fraud, Wilson was most assuredly not one of them. It was Wilson, as noted earlier, whom B. D. Williams had approached in order to change the name of his territory to “Colorado.” (Wilson, in an interesting side note, was intimately familiar with the concept of changing names. He had been born Jeremiah Jones Colbath, named for a wealthy neighbor whom his parents hoped would become the boy’s benefactor. He changed his name to Henry Wilson shortly after his twenty-first birthday.)

Clearly the name Idaho had survived and prospered in the three years since it was rejected in favor of Colorado. After Wilson proposed it for the new territory in the northwest, another senator, Benjamin Franklin Harding of Oregon, asserted the original “meaning” of the word, “gem of the mountains,” and insisted it was appropriate for this new territory. With very little debate, the name “Idaho” was agreed to, and this time no eleventh-hour reprieve was requested. The bill passed Congress, and Idaho became a huge northwestern territory on March 4, 1863. The next year Montana was separated from it, and Ashley got to use his favorite name after all. President Benjamin Harrison approved Idaho as the forty-third state of the Union on July 3, 1890.

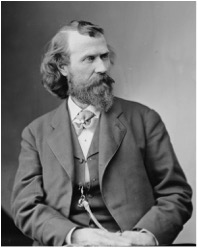

Joaquin Miller

The name Idaho, even after statehood was achieved, did not cease to arouse curiosity and study. By this time William O. Stoddard had given his account of George M. Willing’s fabrication of the name, but that story was looked upon skeptically by many.

One of the most famous defenders of the word and its supposed meaning was a California writer/poet named Joaquin Miller. A colorful character, Miller has been called the “Poet of the Sierras” as well as the “greatest liar this country has ever produced.” In 1883, writing for a Philadelphia magazine, Miller wrote of his own experience when he first heard the word (or words) “E Dah Ho!” spoken by Indians while he was traveling to the gold fields of the northwest around 1861. Miller tells of a pioneer named Colonel Craig with whom he was traveling and the Indian guide with them who exclaimed “Idahho (sic)!” when gazing at the sun dawning over the mountains. Writes Miller, “‘That shall be the name of the new mines,’ said Colonel Craig quietly, as he rode by his side.”5

Miller’s account, while dramatic, has gradually come to be seen as the product of a very active imagination, though for years his stories were believed and reproduced as fact. There are some glaring inconsistencies with Miller’s version of events, however, the most obvious being his attribution of the name to a northwestern tribe of Indians instead of one in the Pike’s Peak area where the name was originally proposed. The other conspicuous problem with Miller’s, and Willing’s for that matter, definition of the word has to do with the concept of a “gem.” The idea of an earthen mineral to be mined and used as a valuable trade item is, as one author puts it, “a white man’s notion, quite foreign to the thought of...American Indian peoples.”6

The timing of Miller’s story is also suspect. He claims to have heard the word for the first time in 1861, and even proposes that in September of that year he may have been the first to use its current spelling. But the bill to create Idaho Territory was proposed in Congress in April of 1860, over a year before Miller’s supposed contribution. Still, scholars familiar with Indian languages have attempted to find a suitable aboriginal derivation, just in case one exists. Even the languages of the Arapahoe and Ute Indians who lived in the Colorado Rockies have been studied, but no such word or phrase has ever been found that might approximate “Idaho” with its alleged definition.

And so it appears that Idaho is what it has become—a northwestern state with such awesome beauty that the moniker “gem of the mountains” could and does certainly apply. Perhaps, though, the real “gem” is the starchy, brown vegetable that has brought to the state such a prosperous agricultural industry. It seems that no matter its true derivation, the word Idaho now has real meaning.

End Notes

1. Peterson, F. Ross, Idaho: A Bicentennial History (New York, 1976), p. 3.

2. “Letters of George M. Willing, ‘Delegate of Jefferson Territory,’ With an Introduction by LeRoy R. Hafen,” The Colorado Magazine , Vol. XVII, No. 5, p. 186.

3. “Footnotes to History,” Idaho Yesterdays , v. 8, no. 1, p. 33.

4. Idaho Yesterdays , vol. 8, no. 1, 1964, p. 35.

5. Miller, Joaqin, “Idahho!,” The Continent , Vol 111, no. 22, May 30, 1883, p. 689.

6. Idaho Yesterdays , vol. 8, no. 1, 1964, p. 36.