FLORIDA

Because it is evident that any recount seeking to meet the December 12 date will be unconstitutional, we reverse the judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida ordering a recount to proceed.

—U.S. Supreme Court, December, 2000

I’m back to livin’ Floridays

Blue skies and ultra-violet rays

Lookin’ for better days, lookin’ for better days

Lookin’ for Floridays

—Jimmy Buffet, Floridays

The Debacle

Florida is the land of hanging chads and butterfly ballots. Since the election debacle of 2000 it is a name that strikes fear into the hearts of voters and candidates alike. The presidential election that wouldn’t end began the night of November 7, 2000, a night which heard news analysts from virtually every TV network conclude more and more confidently that “it all comes down to Florida.” And indeed it did.

And down to Florida went throngs of news crews and hordes of attorneys, filling up hotel rooms at a rate generally only seen there during Spring Break. Finally, on December 13, after a stunning 5-4 decision by the Supreme Court, Al Gore conceded defeat to George W. Bush, brother of then Florida Governor Jeb Bush, after weeks of election controversy. The experience tagged Florida with a whole new reputation and colored Bush’s presidency for the next four years.

Of course, before the state was saddled with this reputation, the name “Florida” conveyed many other diverse images—sun-drenched Miami Beach, Cape Canaveral and the space shuttle, the Everglades with its ferocious alligators and mosquitoes, the Keys (from the Spanish cayos meaning “small islands”), Dave Barry, Don Johnson, Janet Reno, Jimmy Buffet, Gloria Estefan, and of course, Walt Disney World.® It is college students on Spring Break, senior citizens in retirement communities, and names of cities that all seem to be followed by either “Bay” or “Beach.”

Florida is also famous for its population of Latin Americans. Dade County, which spans most of Miami, has the highest rate of immigration of any county in the United States; over half of its population are immigrants, according to the 2000 census. While the perception is that all of these immigrants come from Cuba, it turns out that people from many Central and South American countries immigrate to Miami every day. It was, in fact from Puerto Rico that Ponce de Leon set sail in 1513, eventually landing on the American mainland and bestowing on the area the name that has come to symbolize election mayhem.

Ponce de Leon

When Columbus “discovered” America, what he actually found were many of the islands in the Caribbean, as opposed to the side-of-a-barn that is the North American continent. And from 1492 to at least 1513 the exploration efforts of the Spanish and Portuguese were concentrated in these islands and on the search for a water route to the Orient. Coincidentally, in the same year (1513) two significant “discoveries” were made by Spanish explorers—Vasco Nuñez de Balboa crossed the isthmus of Panama and christened the “South Sea,” or Pacific Ocean, claiming all land adjacent to it for Spain; and Ponce de Leon made his famous discovery of Florida.

For more than twenty years after Christopher Columbus’ voyages there was uncertainty in Europe about the continental nature of his discoveries. Columbus himself went to his grave convinced, at least outwardly, that Cuba was a peninsula of Asia. This, of course, was disproved, as the Spanish continued to explore the islands of the West Indies. And so, when Juan Ponce de Leon went looking for the island of Bimini and the fabled “Fountain of Youth” in 1513, and instead found the continent of North America, he assumed that what he had found was another island.

Ponce de Leon was a Spanish nobleman who joined Columbus on the second of his four voyages to the New World. In 1502 he returned to Hispaniola (the island of Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and eventually was named adelanto , or governor of Puerto Rico. While at that post, he heard the natives talk of the island of Bimini, which reportedly contained a fountain with magical healing powers such that an old man who drank from it would regain his youth. Probably more enticing, and more believable, were the stories that the island also contained gold. Ponce obtained from King Charles V of Spain a charter to discover and settle Bimini, a charter that made him governor for life.

The most comprehensive description that survives Juan Ponce’s expedition is that of Antonio de Herrera, grand historiographer of America and Castile in the early 1600s. The work is entitled “Decription of the West Indies” and is one of eight sections of a larger work entitled “Historia General de los Hechos de los Castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Océano” ( General History of the Deeds of the Castilians on the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea ) originally printed in 1601. Though Herrera’s work was published ninety years after Ponce’s first voyage to North America, it is considered authoritative because he, unlike other historians of that time, had access to official government documents, presumably including first-hand accounts and journals of Ponce’s voyage, documents that today are lost to history.

Ponce departed Puerto Rico on March 3, 1513 with three ships. Three and a half weeks later, on March 27th—Easter Sunday in Spain, commonly called Pascua Florida (literally “Flowery Passover”)—they sighted land. It was not uncommon in that era for Spanish explorers who discovered new territory to name it for the feast day upon which it was found. In fact, according to George R. Stewart in Names on the Land , at least one Spaniard sailing in 1568 along the coast of California used no other means:

As he sailed still farther north, [Sebastian de] Viscaino showed himself wholly without imagination. He looked in the calendar, or else he asked one of his Carmelite friars, and then he named the place after the saint of that day. So, even without the log-book, a historian can trace that voyage by the names given.

And so on April 2, according to Herrera

they anchored near shore, in 8 brazas (fathoms) of water. And thinking that this land was an island, they called it La Florida, because it was very pretty to behold with many and refreshing trees, and it was flat, and even; and also because they discovered it in the time of Flowery Passover, Juan Ponce wanted to agree in the name, with these two reasons.1

In 1521 Ponce de Leon wrote Charles V of his intention to return to “that island” and create a settlement. “I also intend to explore the coast of said island further, and see whether it is an island, or whether it connects with the land where Diego Velazquez is [meaning New Spain, that part of Mexico which by that time had been occupied by Cortes, discovery of which was claimed by Velazquez] or any other...I shall set out in five or six days.”2 Ponce de Leon did indeed return to Bimini and, in a fight with the natives, received a wound in his leg. He left immediately for Cuba where he died of his injury.

The Line of Demarcation

In 1493 Pope Alexander VI issued a bull (or papal decree) dividing the non-Christian world into halves. The following year the Treaty of Tordesillas was signed by Spain and Portugal, the two benefactors of the papal bull, establishing the line of demarcation at 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Because Florida lies west of that line (i.e. in the Spanish half of the world), Spain laid claim to Ponce de Leon’s discoveries, no matter if they were islands or continental. On early maps of the sixteenth century, while mapmakers were unsure of what Florida was, it clearly was represented as a Spanish holding. Thus, the name “Florida” applied to the North American continent even before the name “ America ” did, and it is one of the few surviving names applied by those early conquistadors.

From the time of Ponce de Leon’s discovery until about 1560, several Spaniards made serious attempts at establishing colonies in Florida, which is to say anywhere in the southeastern portion of the continent. One of these attempts was made by a royal judge named Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, who received permission to settle the “land of Chicora” in the early 1520s. “Chicora” was the lyrical name taken from an Indian slave who sparked Ayllón’s interest by describing his homeland (actually in what is now South Carolina) as having fertile valleys with abundant gold. Due to disease, starvation, and conflicts with natives, Ayllón’s settlement was a fast failure, and “Chicora” turned out to be one in a long series of disappointments for the Spaniards in North America. The most famous of these disappointments was that of Hernando de Soto who, like others including Ayllón and Ponce de Leon, died in the attempt. Spain lost interest in settling Florida until it became clear that another country was trying to encroach on their claim.

In 1562 it was the French who finally got a foothold on the Florida coast. Jean Ribaut claimed the St. John’s River for France and built a fortress, which was abandoned a year later. In 1564 the French built Fort Caroline near what is now Jacksonville, a more successful effort, and this time got the attention of the Spanish. Pedro Menendez de Aviles moved into the area with the intention of attacking the French fort and ridding Spain of the French invaders. On September 8, 1565, he established his base of operations in a grand ceremony, christening his new settlement “St. Augustine” after the name they gave to the river upon which it was founded. The fortress would go down in history as the first permanent European settlement in what would become the United States of America. Menendez’ attack on Fort Caroline was gruesomely successful, and all of the inhabitants of the French settlement were murdered at a place that would take on a Spanish name commemorating the slaughter: Matanzas— massacre .

Florida Natives

Once the maps began to consistently reflect North America as a continent, the area of what is now Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi was just as consistently shown as “Florida” or “Spanish Florida,” and Spain kept a firm grip on it despite the encroachment of England, France, and later the United States. The effort came at the expense of the natives of the peninsula, who were early casualties of European exploration. During the seventeenth century the Spanish used the mission system to “pacify” the natives, but massive epidemics as well as constant conflict with the Creeks to the north contributed to the destruction of many of the missions and the decimation of the native Florida tribes—the Timucua, Ais, Calusa, Apalachee, and others who were notable for their distinct language stock.

The Seminole Indians, now so famous as the dominant Florida tribe, (not to mention namesake for the mascot of Florida State University) were actually not natives of what is now Florida. The Seminoles were actually Creeks who moved south from current Georgia and Alabama, filling the void left by the decimated Florida tribes. These Creeks migrated into Florida to avoid conflict with the increasingly difficult English settlers in South Carolina, and their numbers increased over the decades as they gave refuge to escaped slaves of African descent and to more and more Creek natives. The Indian Removal policies of the United States in the early 1800s, and the efforts by Andrew Jackson, among others, to enforce them, pushed even more Creeks into Florida. The name Seminole derives from the Spanish Cimarrón meaning “wild ones” or “free ones.” The Florida Seminoles would go on to engage in some of the bloodiest battles, indeed wars, fought by any native tribe in North America in an effort to keep their Florida land.

The Incredible Shrinking State

About twenty years after the founding of St. Augustine the English set up their colony at Jamestown in what is now Virginia and began to push southward. Almost eighty years later, La Salle would navigate the Mississippi River to its source and claim it for France. Once the French settlement of New Orleans was established, Spanish Florida was no longer physically connected to Spain’s dominion in Texas and the southwest.

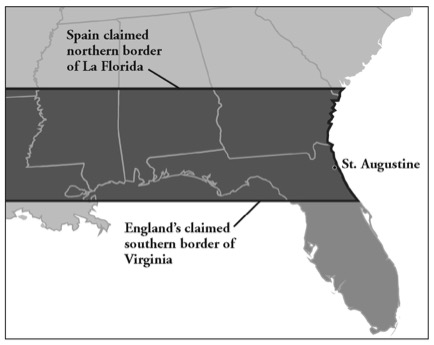

The first diplomatic border dispute between Spain and England in North America occurred in 1670 when Spain declared the northern border of Florida to be a line running west from a point in Port Royal Sound. This would have given Spain the entire state of Georgia and the southern tip of South Carolina. England countered with its own claim, placing the southern boundary of its Carolina grant at 29˚ North latitude, which would have consumed about a third of present day Florida, including the Spanish settlement at St. Augustine.

But if the northern boundary of Florida was fuzzy, the western boundary was even more so, in part because relations between Spain and France were friendly, based on a mutual desire to drive the English off of the North American continent. When La Salle made his attempt in 1685 at placing a French settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi, the Spanish attempted to intercept and stop him (they need not have bothered, as the effort was doomed to failure); but, when Pierre le Moyne Sieur d’Iberville planted a French settlement first at Biloxi, then at Mobile, the Spanish—rather than try to thwart the attempt—were simply relieved that they were so far west of Spain’s tenuous position at Pensacola and remained friendly with the French at Mobile for twenty years.3

Floridas

Borders were finally established when the British obtained Spanish Florida at the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which ended the Seven Years War in Europe. In one proclamation on October 7, 1763, the English established borders for its new territory and divided it in two. East Florida’s northern boundary began at the confluence of the Chattahoochee and the Flint Rivers, went due east to the headwaters of the St. Mary’s, and then followed that river to the Atlantic Ocean. West Florida was bordered on the north by the 31st parallel, on the west by the Mississippi River, and on the east by the Chattahoochee down to the Appalachicola, and down the Appalachicola to the Gulf of Mexico. The legacy of this division today is the jag in Florida’s northern border where it meets the Chattahoochee River, the same river that marks Georgia’s western border. Though these borders would change and be disputed, they closely reflect the current borders for the state of Florida.

One of the most hotly contested border disputes in U. S. history began when, in 1764, Great Britain rather innocently moved the northern border of West Florida from 31° to 32°28’ North latitude in order to include in the new territory the Natchez district, which was situated in what would become Mississippi. Making this change was a simple formality at the time, because Britain was the recognized “owner” (assuming, of course, that you weren’t asking the Creek Indians) of the land both north and south of the changed border. But when the Floridas were ceded back to Spain after the American Revolution in 1783, ambiguous references were made to the northern border in the Treaty of Paris, and so Spain and the United States disputed its placement. The West Florida controversy (see Mississippi) would continue until the signing of the Adams-Onis treaty in 1821, in which Spain ceded the Floridas to the United States.

It was while Florida still belonged to Spain, however, that its eventual borders were finally settled. According to Florida historian Charlton A. Tebeau:

“ ...When Louisiana became a state in 1812 the eastern boundary was fixed at the Iberville River. In that same year Governor Holmes organized the region between the Iberville and the Perdido as a county of the Mississippi Territory. Though still referred to as East and West Florida and having separate governments, the boundaries of the once extensive Spanish La Florida had now been reduced to the limits of present-day Florida.”4

Once the United States gained control of Florida one might think the boundaries of the new territory would be more easily settled. But in fact they became perhaps even more complicated with the creation of “Middle Florida” and contentions by some that the entirety of Florida should enter the Union as two or even three states. Some Floridians also maintained that parts of Florida should be annexed by Georgia and/or Alabama, and both of those states extended invitations for Florida to do just that. These disputes continued for some thirty years until the matter was eventually resolved on March 3, 1845, when Florida, borders intact and all the parts of the territory united, became the 27th state to join the United States of America. President John Tyler signed the statehood resolution on the last day of his presidency.

End Notes

1. Kelley, James E., Jr., “Juan Ponce de Leon’s Discovery of Florida: Herrera’s Narrative Revisited,” Revista de Historia de America [Mexico] 1991 (111): 31-65.

2. Weddle, Robert S., Spanish Sea: The Gulf of Mexico in North American Discover 1500-1685 , (College Station, 1985), p. 48.

3. Tebeau, Charlton W., A History of Florida . [Coral Gables, 1971] p. 62. Tebeau, p. 105.