CONNECTICUT

I am an American. I was born and reared in Hartford, in the State of Connecticut—anyway, just over the river, in the country. So I am a Yankee of the Yankees—and practical; yes, and nearly barren of sentiment, I suppose—or poetry, in other words.

—Mark Twain, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

“That was the worst day of my presidency”

—President Barack Obama,

on the Sandy Hook Elementary School

shooting, December 14, 2012

Insurance and Basketball

It is a word that can make one think of something as quaint as a New England style town square, or something as modern as college basketball, or something as mundane as the insurance industry. Connecticut , the name of the third smallest state in the U.S., seems packed with images. A perfect rectangle with imperfect borders, Connecticut is one hundred miles from east to west and 50 miles from north to south; even the slowest driver could tour the state in less than a day. It’s where affluent New Yorkers live; it’s Yale; and it’s the place from whence appeared Mark Twain’s Yankee in King Arthur’s court.

Connecticut is proudly known as the “Constitution State.” This title refers to The Fundamental Orders which were established in the colony in the late 1630s, ostensibly the first constitutional document in America.

Basketball fans add “The University of” to “Connecticut” to name arguably the best women’s basketball program in history and a pretty decent men’s hoops program to boot. But they like to shorten it. Rather than the eleven-syllable mouthful that officially names the institution, they speak of “UConn”, and pronounce it “Yukon”. To the uninitiated, this of course may produce images of Eskimos wearing fur parkas throwing a frozen basketball into a hoop as baby seals look on.

Interestingly, many places in Connecticut are well known as Connecticut places, even to complete outsiders. Names like New Haven , Hartford , Stamford , and Greenwich are instantly recognizable as Connecticut towns, even though none of them have populations greater than such lesser known places as Garland, Texas or Naperville, Illinois. It is no doubt their history, and the history of their state, that makes them famous. Connecticut seems the epitome of rural New England, of quaint farmhouses, rolling green meadows, and puritan values spiced with a touch of revolutionary spirit.

And then there is one Connecticut town whose fame is more recent...and more tragic. At this writing the events of December 14, 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut are perhaps still too recent, too raw to be able to write about their historical impact on the state. But certainly the senseless murder of 26 innocents, 20 of them six years old or younger, will have an impact.

Could you spell that, please?

It has been called the “place with the unpronounceable name.” Un-spellable name is more like it. Seventeenth century Europeans, just like schoolchildren today, struggled mightily with how to represent in writing the word they heard uttered by the natives that described the Connecticut River Valley. But spell it they did, in lots of different ways—Connittetuck, Counitegou, Kwenihtekot, Quanehta-cut, Quenticutt, Quienetucquet, Quinatucquet, Quinnehtukguet, Quinnehtukqut, and Quonehtacut, just to name a few.

In 1665 the Duke and Duchess of Hamilton in England attempted to claim a land grant that had been conferred upon an ancestor of the duke. In the petition, however, the name of the valley—which everyone involved knew to be the Connecticut River valley—was spelled “Converticu.” The appeal was denied when the Connecticut Assembly rather cheekily “protested [their] ignorance of any ‘Converticu’ River.”1

But thirty years earlier the English were just learning of this river from the natives they traded with. The Puritans wrote and spoke of Connecticut with a covetous—if cautious—tone, for once Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) were established and settled, the great Puritan Migration of the 1630s began to pour into new towns and villages of New England, and more space was quickly needed.

However you spell it, Connecticut means “on the long tidal river” or “place of the long estuary.” It is Algonquian, and was used by several different tribes in the area south of Massachusetts—Narragansett and Nipmuck among others—all of whom spoke dialects of Algonquian. The Indians told the colonists about the Connecticut valley, about its rich, fertile land and bountiful river, which was used as a trade route into prime beaver hunting grounds. They also talked of the Dutch who were pushing into the area from New Amsterdam.

The Dutch, incidentally, solved the problem of the unspellable name by providing their own. In 1614 Adriaen Block (after whom Block Island would be named) sailed up the Connecticut River, the first European explorer to do so, and found its water to be clear and sweet, as opposed to the brackish water of the rivers to the south. He named it “Varshe” or “Fresh” River, and his countrymen quickly began to trade regularly with the Indians who lived on and near its banks.

The Puritans in Massachusetts were told of these Indians, which accounted for much of their caution in attempting to settle in the area. The neighboring tribes called them “Pequot,” which means “destroyers,” and they dominated the Connecticut River valley through force and intimidation. The Pequot were, by most accounts, contentious and belligerent and made enemies of nearly every other tribe in the region in their efforts to maintain a monopoly on trade with the Dutch. The Dutch initially invited the English to join them in settling the valley in order to strengthen the position of the “civilized” Europeans against the “savages.” Even some Indian tribes asked the English to move into the Connecticut region, hoping for a buffer between themselves and the hostile Pequot. But the English balked. They distrusted the Dutch and preferred not to act as “muscle” for one group of natives against another.

The Connecticut Towns

After a few years, however, the situation changed. The Puritans’ need for more space, and the philosophical divisions arising in the Massachusetts colonies, made them more willing to take on the risks of settling among the Pequot and the now openly hostile Dutch. By 1633 two Englishmen had led separate reconnaissance missions into Connecticut territory. The first was Edward Winslow, governor of the Plymouth colony and genuine Mayflower passenger, who rather quaintly proclaimed himself “discoverer” of the river and valley and who began to make arrangements for colonization. The other was John Oldham, a Puritan from Watertown, and an enthusiastic merchant and trader. He and three colleagues ventured to Connecticut by land along the Indian paths. Their report was glowing, even speaking kindly of the natives with whom they had lodged on their journey, and confirming the natives’ descriptions of lush farmland and plentiful fish and game.

These expeditions would spawn three townships in as many years. In September of 1633 Winslow sent William Holmes to set up a trading post on the Connecticut River. A few settlers followed and endured a brutal winter, calling their small village Dorchester after the English town in which many of them had lived before their pilgrimage to the New World. The town would later be named Windsor . In the spring of 1635 John Oldham and a group of settlers from Watertown, Massachusetts established a township at a place the natives called Piquag ; the English named it Wethersfield . And finally, in the spring of 1636 Hartford was founded by a group of Puritans from Newtown (Cambridge). They were led by Thomas Hooker, a fiery and energetic preacher who is commonly referred to as the “Father of Connecticut” because of his wide travels in the region and his efforts in helping to settle disputes among colonists and colonies, and because he was instrumental in the creation of the “Fundamental Orders of Connecticut,” which will be discussed later.

These three towns would gain legal status from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and while technically still under the jurisdiction of the ever-expanding MBC, they began to be referred to collectively as “the River Colony” or simply “Connecticut” with one of its various spellings.

The Warwick Patent

The legality of their towns and settlements under English law was of great importance to most of the English in the New World. With respect to the Indians, they generally satisfied their legal consciences by “buying” the land from them. A tribe would take payment, agreeing to allow the Europeans to settle land which that tribe controlled either by conquest or simple proximity to their own villages. In return, those natives would promise not to harass or hinder the Europeans. These transactions were often fraught with deceit, fraud, and sheer ignorance, but many, especially in the early days of the MBC, were made in good faith with relatively informed consent on both sides.

The procedures for obtaining legal rights to the land from their own government (i.e. the King) were better established, but the results were often just as confused. Generally, once a map of territory was charted, and claim was made to it—as John Smith had done in New England (see Massachusetts)—it was up to the King to decide which of his subjects would be allowed to colonize, improve, and collect rent for said land. In 1622 the Council of Plymouth, which according to its own records was the king’s agent in such matters, attempted to grant to its president, the Earl of Warwick, a charter for some land in southern New England. Unfortunately Warwick never produced the charter, and it has never been found.

Nevertheless in 1632 Warwick drew up a patent authorizing a group of men led by Lord Say and Seale (one person, Lord of both Say and Seale) and Lord Brooke to colonize for profit a section of land described in the patent as

“...All that part of New England in Americah...from a river there called Narrogancett River, the space of Forty leagues...neere the Sea Shore towards the Sowth west...”

The Connecticut River Valley was the obvious object of this patent, and two of the patentees quickly tried to claim land in Windsor, land being technically squatted on by other Englishmen. Their attempts failed miserably, the squatters claiming right to the land by possession (nine-tenths of the law and all that), and the agents of the patent holders went home empty-handed.

Another set of patent holders, however, successfully established a new colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River in 1636, naming it Saybrook after the two primary benefactors. Saybrook became the fourth major township in Connecticut and was governed initially by John Winthrop, Jr. (son of John Winthrop of the MBC, who is often referred to as the “Father of New England”). Winthrop, a restless soul in his youth, left Saybrook abruptly at the outbreak of hostilities with the Pequot but would return to a different Connecticut town a few years later and have an enormous impact on the colony’s future, in fact eventually saving it from being absorbed by New York. Saybrook muddled along without him and was eventually absorbed into the River Colony, maintaining control over the lower portion of the river.

War and Orders

The Pequot War, one of the first conflicts between Indians and English settlers, began to brew in earnest with the establishment of the River Colony. The Pequots still dominated the region with respect to other Indian tribes, but the encroachment of the English brought complications, most notably the division of the Pequots regarding which group of Europeans to trade with—Dutch or English. The flashpoint for the war was the Pequot involvement in the murder of John Oldham, aforementioned founder of Wethersfield, on July 20, 1636. When Oldham was killed by Narragansett Indians, a band of Pequot harbored the murderers, and their already hostile relationship with the English intensified to all-out brutal warfare. Almost a year later, at the height of hostilities, a brutal massacre was perpetrated by a group of colonists led by Captain John Mason . This proved the beginning of the end for the Pequot, and within a few months the whole tribe was virtually annihilated.

Partly because of the Pequot hostilities, the River Colony in 1637 set up a cursory legislature, which would provide for the defense of the three original communities. But for Thomas Hooker the need for a more formal government was of primary importance. On May 31, 1638 he delivered a famous sermon which outlined a civil government to complement the laws of the church. Later that year the River Colony adopted the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut , incorporating much of Hooker’s sermon into what would now be civil law. This document is often referred to as a precursor to the U.S. Constitution, thus conferring the nickname, “Constitution State” on what was now still a loyal English colony.

New Haven

While New Haven is now indelibly associated with Connecticut, it began as a completely separate colony. New Haven was founded in April of 1638 by a group of Puritans from Massachusetts led by John Davenport. Situated at the Indian village of Quinnipiack, New Haven from its founding maintained a separateness from the River Colony. Indeed as New Haven thrived and prospered, it added new towns—Milford, Stamford, Guilford, Branford, and Southold on Long Island—to what in 1643 was officially consolidated into New Haven Colony .

For almost two decades the Connecticut River Colony and New Haven Colony functioned independently, each a member of the short-lived New England Confederacy . The River Colony was governed by John Winthrop, Jr. who only a few years earlier had founded and then abandoned Saybrook, while New Haven thrived under the leadership of John Davenport.

The fortunes of these colonies changed with the restoration of Charles II to the English throne in 1660. Once again concerned about the legality of their colony Connecticut sent Winthrop to England to attempt to negotiate a new royal charter. Even though he was forced to admit the non-existence of the Warwick Patent, Winthrop was able to convince the King and his court of the value of Connecticut as a separate colony, especially as a foil to that thorn in the Royal side, Massachusetts, and Winthrop was granted all he asked for and more.

The “more” was a set of boundaries so generous and so non-specific that it created border disputes on virtually every edge of the colony. It also created a major disturbance in New Haven, because the charter empowered Connecticut to absorb New Haven completely. New Haven, especially the aging Davenport, fought bitterly to maintain its independence, but Connecticut made generous offers and slowly enticed most of the towns in New Haven into annexation. New Haven itself held out for several years, but in 1664 found itself faced with the choice of rule by Connecticut or rule by the Duke of York (James Stuart, brother of Charles II and heir to the English throne). The duke had just been granted the territory south of Connecticut, land which the Dutch had called New Amsterdam but which had been seized by the English and renamed New York. New Haven chose Connecticut on January 5, 1665, the day the Colony of New Haven ceased to exist.

Except for the two notable exceptions below, Connecticut would do very little morphing of shape from this point on. On January 9, 1788 Connecticut, the “Constitution State,” ratified the fledgling U.S. Constitution. In doing so, it became the fifth colony to join the United States.

Connecticut’s Boundaries

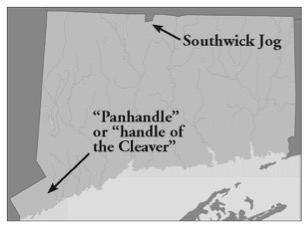

Connecticut’s borders contain two interesting anomalies. One is known as the Southwick Jog. It is a tiny notch of land which is set into the otherwise straight line that marks the border between Massachusetts and Connecticut. The jog (near Southwick, Massachusetts) has its origins in a survey performed in 1642 by Nathaniel Woodward and Solomon Saffery which was supposed to determine the border between the two colonies. The story goes that the two men surveyed about half the line, but then turned back to Boston for fear of a confrontation with Indians. They took a boat from Boston around Cape Cod and up the Connecticut River to complete their survey. When it was completed, the eastern half of the line was eight miles south of the western half, and the location of the “correct” border was now even more in dispute. The disagreement raged on for a hundred and fifty years until finally, in 1804, Connecticut agreed to a compromise that gave a tiny portion of the Congomond Lakes area to Massachusetts.

The other anomaly in Connecticut’s borders is sometimes called “the handle of the cleaver,” or more commonly “the panhandle.” It is the result of conflicting Royal charters (go figure) for Connecticut and New York. This conflict was resolved relatively quickly in 1683, with New York conceding the panhandle to Connecticut, taking for itself a strip of land to the north, which is sometimes called “The Oblong.”

End Notes

1. Robert C. Black III, The Younger John Winthrop (New York, 1966) p. 288.