COLORADO

I’ve seen it rainin’ fire in the sky

The shadow from the starlight is softer than a lullaby

Rocky Mountain high, Colorado

—John Denver,

Rocky Mountain High

To my friends in New York, I say hello

My friends in L.A. they don’t know

Where I’ve been for the past few years or so

Paris to China to Colorado

—One Republic,

The Good Life

Mountains

Colorado invites us into the rugged Rocky Mountains of the American West. It calls us to climb its snow-capped peaks, its forbidding ridges, its engaging summits, and then encourages us to careen down them at unnatural speeds with only a couple of waxed boards strapped to our feet for some perceived measure of control. Aspen, Vail, Telluride—the ski resorts of the mountains are just as easily associated with Colorado as the big cities of the eastern slope—Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs. Colorado’s four ninety-degree angles and two pairs of parallel sides contradict its name and its reputation. Not only does the boxy shape of the state defy the curves, crags, and crests of the mountains for which it is so famous, it also ignores the winding river from which it took its name.

Colorado, like many states, has its own Hollywood stereotype. Unlike her northern neighbors with whom the state shares the largest mountain range in North America, Colorado’s mountains seem less conducive to solemnity and peace than to recreation and challenge. Hollywood uses these mountains as a backdrop for films about human endurance and adventure—films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid , City Slickers , How the West Was Won , and True Grit .

Colorado’s mountains are its very essence, even though fully a third of the state is comprised of flat plains and farmland that looks more like its next-door neighbor, Kansas. The state cultivates an image of rugged, western culture—Denver hosts a major stock-show and rodeo each year, and Colorado Springs is home to the Rodeo Hall-of-Fame. But it was the miners of the mountains, not the ranchers of the plains, who truly created Colorado.

Finding the River

Colorado takes its name from the most dominant river in the American Southwest. One source of the Colorado River is in the state of Colorado, but the river is fed by a system of tributaries that reach northward into Wyoming and westward to California. The bulk of the river’s basin is the eastern half of Utah and virtually all of Arizona, while the lowest section divides the Mexican states of Baja California and Sonora, then the river empties into the Sea of Cortés. Providing water to what is otherwise a massive desert, the river boasts some of the most wondrous landmarks in North America.

Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1959, creating Lake Powell--a prime vacation spot for house boaters--along the Arizona-Utah border. Lake Powell was named for John Wesley Powell, the first white man known to have navigated the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. This he did in 1869 with a small crew after having lost his right arm in the Civil War.

Further down the river sits another impressive dam. Sometimes called “Boulder Dam” after the name of the canyon in which it was built, Hoover Dam was officially named for the 31st president, Herbert Hoover, who presided over its early development in the 1920s. Hoover Dam forms Lake Mead, named for a Commissioner of Reclamation Dr. Elwood Mead, who designed much of the Boulder Canyon Project.

Between these two dams the Colorado River flows through perhaps the most famous natural landmark in the country, possibly in the world—the Grand Canyon. One of the seven natural wonders of the world, the Grand Canyon, rises along the banks of the Colorado River for 277 miles. From there, what’s left of the water in the Colorado River winds south to form the border between California and Arizona, and then continues into Mexico where it empties into the Sea of Cortéz.

Naming the River

Native tribes of the Southwest had their own names for the Colorado River, but they all meant “red river.” The A’a’tam a’kimult, or Pima Indians, called it “Buqui Aquimuri.” The Kwitcyana, or Yuma, Indians who lived along its banks near its mouth called the river “Haweal.” The redness of the water is—and was—caused by iron in the abundant silt washed along the river through the southwestern desert.

While vital to the arid Southwest for the water it supplies, the Colorado River was considered useless to Europeans when they found it in the 1500s because it was impossible to navigate. Its quick current and many rapids forbade even the smaller vessels of the world’s sailors from traveling very far. Perhaps for this reason, credit for “discovering” the river usually goes to “the Spaniards” and not to one Spaniard in particular, as if the accomplishment of finding it was simply too unimportant for anyone to claim for himself. When a name is mentioned in connection with the feat, it is generally one of three.

The first of these is Francisco de Ulloa who sailed to the north end of the Gulf of California in 1539 hoping to explore the Pacific Coast, the Spaniards still believing the Baja peninsula to be an island. Ulloa, it is said, did not so much find the Colorado River as sense it, which is to say he noted the current flowing from the north, and the silt being deposited by it. At any rate, he turned south to head back to New Spain and died shortly thereafter, either lost at sea or stabbed by a fellow sailor, according to conflicting reports.

The next Spaniard to discover the Colorado was Hernando de Alarcón whose small fleet sailed north from Mexico to support the massive overland expedition of Coronado in 1540. Alarcón would be the first European to sail into the Colorado River, though the current against him was so strong that he needed one of his smaller ships to do so, and even then he was unable to get very far. It is unclear how far north Alarcón traveled, but some researchers maintain he got no further than the current international border. Oddly, he named the river Rio de Buena Guia or “River of Good Guidance.”

The third Spaniard to occasionally get credit for the discovery is Juan de Oñate who explored the American Southwest in 1605 looking for a water route to the South Sea (Pacific Ocean). By the time of Oñate, the Spaniards had given the river other names including Rio de Cosninas (a Spanish version of the name of a local Indian tribe), Rio de San Rafael, and Rio de Tizon (“Firebrand River”). Oñate’s contribution to the discovery is that he added the name Rio Colorado to the list. Technically speaking, it was a padre/historian named Zarate Salmeron who studied the records of Oñate’s 1605 voyage in 1626 and wrote “Rio Colorado” as the river’s name, noting Oñate’s description of the nearly red water.

Around the beginning of the 18th century, the name Rio Colorado began to appear on maps, though it would be almost two more centuries before the name would apply to a section of river in the state that bears its name. Not until 1921, at the request of the state of Colorado, was the section of the river then known as the “Grand River” renamed “Colorado River.” Now, at long last, there was a Colorado River in Colorado.

There was, however, and still is a Colorado River in Texas, and a Red River to boot (not to be confused with the Red River of the northern plains that forms part of the border between North Dakota and Minnesota). None of these is at all connected to the Colorado River that gave the state its name, except that all are, or were—one must assume—red. And to seriously belabor the subject of color, while there is no Red River in Colorado, there is a White River, which winds down from the Rocky Mountains and into the Green River, which delivers water to…the Colorado.

Barrier Land

The European powers of the 16th and 17th centuries recognized Spain’s claim to the American Southwest as far north as New Albion, or what is currently Oregon and Idaho. But when Rene Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle claimed Louisiana for France in 1682, a boundary seemed in order to separate the claims of the two countries. That boundary was determined to be the Continental Divide, though where that line lay was more theoretical than physical. In fact, the region that is now the state of Colorado is referred to in history books as a “buffer land,” “barrier land,” and “no man’s land” because of its sparse settlement until the 1800s and because it contained the boundary line between Spanish California and French Louisiana.

The Spanish did not settle the region, but a few Spanish explorers wandered through what they named the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) mountains in the southern part of the state. The first of these was explorer Juan de Uribarri who in 1706 left Santa Fe and explored the region of what are now called the “Spanish Peaks” just west of Walsenburg, Colorado. The native Indians called these twin mountains “Wahatoya” or “Breasts of the Earth” for what must be obvious reasons. Uribarri declared the region to be the province of “San Luis,” but then went back to New Mexico never to return, allowing his appellation to fade. Today “San Luis” refers to the highest desert in the United States, the San Luis Valley of south central Colorado.

International politics concerning the parallelogram we call Colorado changed slightly when France transferred the western half of Louisiana to Spain in 1762, making a boundary no longer necessary. But a border became critical around 1803 when, through the machinations of Napoleon Bonaparte, Louisiana passed back from Spain to France (see Louisiana) and then quickly to the United States. Once the Americans began aggressively settling and exploring their new western frontier, the limits of that frontier needed firm definition.

In 1806, Zebulon Pike made his famous journey westward under the authority of General James Wilkinson. Ostensibly looking for the headwaters of the Arkansas and Red Rivers, what Pike discovered was the mountain that now bears his name. He made a now famous, yet unsuccessful attempt to climb to the summit of what he called “Grand Peak,” then continued his explorations until he was arrested by the Spanish for trespassing. Pike and his men were released a few months later, but his journals and maps were confiscated by the Spanish, and not returned to the United States for over a hundred years. Even so, Pike published an account of his journey that quickly became a bestseller and influenced all future exploration of the Southwest.

Pike also influenced the names of scores of places in the United States. Ten states (though not Colorado) contain a “Pike County,” and several towns, an island, a national forest, and even a Navy ship were named for him. And while he gave the name “Grand Peak” to the mountain he attempted to climb, the name “Pike’s Peak” would become popular fifty years later through the writings of another famous American explorer, John C. Fremont.

In 1819 the U.S. and Spain agreed on a border with the Adams-Onis Treaty. The boundary stair-stepped up over Texas and divided what is now Colorado between the two countries. Thirty years later, with the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, that border was erased by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Now the American frontier was unobstructed all the way to the Pacific Ocean, and the almost instantaneous discovery of gold in California gave rise to the migration of a new breed of Americans.

Miners

In the 1850s prospectors and other opportunists filed over and around the Rocky Mountains on their way to the California gold fields. In May of 1854 the territory of Kansas was created out of land that spread from the western border of Missouri all the way to the Continental Divide, including a large chunk of what is now southeastern Colorado. Then in 1857 a devastating market collapse and subsequent economic depression launched thousands more men into the adventurous trade of mining. Men who could no longer find work as carpenters, storekeepers, even doctors, and who had lost fortunes yet still had families to support, decided to follow rumors of gold and silver into the mountains of the west. Some historians assert that the panic of 1857 spurred the onset of the Civil War. What is much more certain is that it spurred the creation of Colorado.

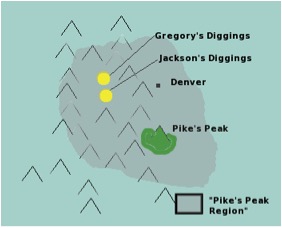

Rumors of gold in the Rocky Mountains had been swirling for years by the time some small deposits of gold were found in streams near what is now Denver in 1858. News of the find along Cherry Creek, so named for the chokecherries that grow along its banks, spread quickly, and miners from the Midwest and points further east began to move into the inhospitable plains and foothills just east of the mountains in what was then western Kansas Territory. Then in 1859, George Jackson found a small deposit of placer gold near what would become Idaho Springs, and a few months later, and not far away, John Gregory found an even larger vein of gold in Clear Creek. While not exceedingly large finds, “Jackson’s Diggings” and “Gregory’s Diggings” meant the hope of wealth to the economically depressed communities in the East and Midwest. Storekeepers closed their shops, farmers left their fields, and whole families moved to western Kansas, eastern Utah, and northern New Mexico Territories to try their luck at mining.

While these gold finds were situated about eighty-five miles north of Pike’s Peak, the whole region, including Denver City, became known informally as the Pike’s Peak region, as that mountain was the most famous landmark anywhere near the mines. The historical exclamation “Pike’s Peak or Bust!” scrawled on the side of covered wagons, referred not to what we now know as Pike’s Peak, but to land slightly north of the I-70 corridor that winds through the Rocky Mountains. So many miners, tens of thousands, had flooded into these mining communities in 1858 that the clamor for local government, which is to say statehood, came before the year’s end.

Jefferson

The first attempt to organize a new territory out of the Pike’s Peak region was instigated in the U.S. House of Representatives early in January of 1859. The name proposed was “Colona,” but the measure failed quickly. The feeling was that just because a bunch of men had moved into the area to dig for gold didn’t oblige the U.S. Congress to grant them statehood.

Meanwhile, the miners in the camps needed and wanted local government. They took matters into their own hands and created the “Territory of Jefferson,” then began electing officials and passing laws. The miners also sent a delegation to Washington to press for territory status. When they began levying taxes, however, the rogue government fell apart, and the miners waited for Congress to act on their request. When the petition was brought before the House of Representatives on January 31, 1859, it was quickly referred to committee but not before one amendment could be proposed. Galusha Grow, a powerful senator from Pennsylvania who had recently switched political parties from Democrat to Republican, objected to the name “Jefferson” (Thomas Jefferson being historically associated with the Democratic Party) and suggested the substitution of “Osage,” a regional native tribe. He was told the matter would be discussed in committee and he relented, but it was clear that the name of the state was a politically sensitive matter.

Back home, the miners, much more interested in gaining territory status than in retaining the name “Jefferson” tried out several other potential names:

Yampa, Idahoe, Nemara, San Juan, Lula, Weapollao, Arapahoe, Colorado, Tahosa, Lafayette, Columbus, Franklin—so many in fact, that as late as February 1861, a miner informed his correspondent to direct his letters “to Denver City with the name of this Territory, whatever Congress is pleased to call it.”1

Gradually “Colorado” won acceptance, and the efforts to create a new territory now assumed its new name.

The creation of new territories in Congress was stalled, however, because of the sectional slavery issues that were dividing the country in half. When Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860, and the southern states seceded, the way was cleared for what was left of Congress to begin creating new territories again. In January of 1861 a previously tabled bill to create Colorado Territory was dusted off and voted on. After some machinations that almost renamed the territory “Idaho” (see Idaho), it passed, and Colorado Territory came into existence on February 28, 1861. “Jefferson,” having lost out as the Territorial name, became the name of the most populated county in the new territory, the county which contained the city of Golden, the first capital of the new territory.

For the next fifteen years the miners and other settlers would make several attempts at statehood. The Civil War, political contention, and resentment by easterners of so laudable a status to be granted to “a few handfuls of miners and reckless bushwhackers”2 delayed the process. But finally, with no further attempts to change the name, a constitution was passed, officials were elected, and President Ulysses S. Grant signed the declaration conferring statehood on August 1, 1876. Colorado became the 38th state in the Union in the year of the nation’s 100th birthday, conferring upon the state its nickname, the Centennial State.

End Notes

1. Carl Ubbelohde, Maxine Benson, Duane A. Smith, A Colorado History (Boulder, 1995) p. 95

2. Ubbelohde, et al., A Colorado History , p. 149