ARKANSAS

An old man sat in his little cabin door,

And fiddled at a tune that he liked to hear,

A jolly old tune that he played by ear…

—

Arkansas Traveler

, folk song that has inspired plays, paintings,

and musical renditions performed by, among others, Jerry Garcia

You can tell your Ma

I moved to Arkansas

You can tell your dog to bite my leg

Or tell your brother Cliff

whose fist can tell my lip

He never really liked me anyway

—Billy Ray Cyrus, Achy Breaky Heart

The other man was a stalwart ruffian called “Arkansas,” who carried two revolvers in his belt and a bowie knife projecting from his boot, and who was always drunk and always suffering for a fight.

—Mark Twain, in Roughing It

Stack of States

Several mid-continent states are neatly stacked on top of each other and, with heavy shoulders Arkansas sits near the bottom. Its two most famous cities, Hot Springs and Little Rock are memorable for the imagery they convey. Names like this tend to imply the culture of Native Americans, and indeed this state’s history is rich with that of many tribes of Indians. But the name “Little Rock” was actually applied by French explorers to designate a landmark, la petit roche , along the Arkansas River. And the thermal waters at Hot Springs, while no secret to native Americans, came to be known by the English description of them, a name which came also to be used for the city that was built up around them.

On a map, it appears as if Arkansas may have been embroiled in a few border wars—and lost them all. Sandwiched in between Missouri and Louisiana, the northern border of Arkansas is shoved down a bit as compared to that of Oklahoma, disrupting the straight line that otherwise runs almost undisturbed from the Atlantic Ocean toUtah, until it dead-ends into southern Nevada. This line also gives way to the Jackson Purchase region of Kentucky, and then to a rather illogical looking appendage to Missouri (the “bootheel”—see Missouri) that takes a notch out of Arkansas’s northeast corner. In the southwest corner of Arkansas there is a notch matching the one in the northeast, this one cut by an imposing corner of East Texas. All of these border intrusions make for a rather small, squarish state that historically has been pushed along with the tides of nation building, mostly being managed, formed, and molded by outsiders while its residents struggled to create an identity for themselves.

In the past, the reputation of Arkansas has been mingled with that of its neighbors to create the image of a “southern state,” albeit one on the fringes of the western frontier. It isn’t Creole, but the French influence is apparent (even in the name). It isn’t the deep south of Alabama, but it has a sort of homey, southern flavor. And it doesn’t have the clan-warfare of Tennessee and Kentucky, but its history is spiced with some mountain-boys nuances (bootlegging, bar-fights, etc.) built up within its own Ozark Mountains. The result has historically been a somewhat derogatory reputation as backward and hillbillyish. James R. Masterson, in his 1943 compilation Tall Tales of Arkansaw , opens the book with the chapter “A Dog with a Bad Name,” and describes the state’s reputation this way:

“From Territorial times to the present the reputation of Arkansas has been notorious. Her ill fame has marked her, more than any other State of the Union, as a target for reproach and ridicule. Even today the legend of her absurdity continues to flourish, and she remains a favorite victim of humorists.”1

Another dubious distinction is Arkansas’ notable leadership in the swine industry. The state, which since the 20th century has also had thriving poultry and beef industries, may actually have been no more prolific at pork production than, say, North Carolina. But Arkansas embraced hogs when, in 1909, its largest university, The University of Arkansas, took as its mascot the Razorback hog (or “hawg,” as any good Arkansan will tell you), forever linking the state with swine.

In the twenty-first century, though, mention of the word Arkansas conjures up some notable political memories. Love him or hate him, Arkansas claims as a native son Bill Clinton. The “hate him” may stem more from the scandals surrounding his tabloidesque personal life, than from his policies or administration. The memories will no doubt fade in time, but one must wonder if people in Arkansas long for the good old days when their state’s name was more commonly connected with hogs than with Monica Lewinsky.

Down-Stream People

The first written record of anything approaching the word “Arkansas” was in a journal by Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet in 1673. These two Frenchmen traveled down the Mississippi River farther than any European had yet gone. When they reached the mouth of the Arkansas River, they encountered natives who possessed Spanish trade goods and decided to go no further for fear of a confrontation with their Spanish enemies. These natives were Quapaw, a name morphed by French and English speakers from the tribe’s own word “Ugakhpa,” meaning “down stream people.” The Quapaw are one of the five Dhegiha Sioux people (the others are the Ponca, Kansa, Omaha, and Osage) who once inhabited the Ohio Valley. Some time before European contact these tribes split and moved apart. The Quapaw moved south along the Mississippi River, settling near the mouth of the Arkansas.

Marquette wrote of a village that his Illini guides called “Arkancea,” which, in their own language, meant roughly “land of the down-stream people.” In later years the word would be used by the French to describe the people as well as the region. But even though the French would maintain a friendly alliance with this tribe, the name they would continue to use in describing them was the Illini word Arkansas, and not their own word for themselves, “Quapaw.” The French spoke of the Arkansas Indians as handsome and generous, and indeed the French continued to have a peaceful relationship with the tribe.

In time the southern section of the Mississippi River was referred to as Arkansas Country , which was just south of Illinois Country. These were vague regions, named for the friendly natives living in them, where the French would sometimes set up missions or trading posts, but “settlement,” per se, was not a priority.

Like many aboriginal names, Arkansas was spelled and pronounced many different ways for at least two centuries, mostly by the French who controlled the Mississippi River until 1803. They wrote “Arkansoa,” “Akamsea,” “Arkancas,” and “Akanscas,” among others. Many of these forms lead people to infer a connection between the words Arkansas and Kansas, sometimes even claiming that the two tribes are the same and that the words are interchangeable. The fact that both tribes descended from the Dhegiha Sioux makes it even more tempting to simply declare them identical. But most researchers argue against this connection, noting that the word Arkansas in all of its early forms already contained the ark- prefix, and that early explorers, including Marquette himself, distinguished between the Kansa or Kansas Indians and the Arkansas or Quapaw Indians.2 They also point out that Arkansas is the Algonquian word for a Sioux tribe who called themselves Ugakhpa , while Kansas was a Siouxan word for a tribe who called themselves by the name Kansas .

De Tonti

The person probably most responsible for making the name Arkansas stick is the one-handed explorer, Henri de Tonti, a good friend of the explorer Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (see Louisiana). De Tonti was born to Sicilian parents (his father invented the form of life insurance known as the “tontine”) but spent most of his life in France and joined the French army as a young man. He wore a hook on one arm after having lost his hand in battle and eventually, after transferring to the French Navy, he became a close colleague of La Salle. In 1682, when La Salle became the first European to navigate the Mississippi to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico, de Tonti was by his side.

When in 1685, La Salle attempted to plant a settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi River, de Tonti was stationed at Fort St. Louis on the Illinois River. He left that post and sailed south in an attempt to meet up with his old friend. On the way he left a small group of men at the mouth of the Arkansas River to build a trading house which he called Arkansas Post , and to cultivate a relationship with the Quapaw Indians. After establishing the post, de Tonti learned that La Salle’s attempt at colonization had been a disastrous failure, and that his old friend was murdered by others in his party. De Tonti went on to search for survivors, and continue his military career. He would never return to the trading post he founded.

The Tenacious Arkansas Post

This tiny outpost, built in a flood plain near the Quapaw village of Osotuoy, seemed doomed to failure. The fur trade proved weak, and the post was abandoned by the soldiers around the beginning of the 18th century. It was rebuilt, however, twenty years later by a group of settlers organized by John Law, a Scottish financier who had, for a brief time, a French monopoly on colonizing theLouisiana Territory. Still, though, the colony did not thrive.

The settlers had difficulty clearing the rocky soil for farming, and in 1749 Arkansas Post was attacked by a band of Chickasaw Indians who killed six men and kidnapped eight women and children. To avoid vulnerability to this kind of attack and to the constant flooding, the post was moved to a place called “Ecores Rouges” (Red Bluffs) a few miles upstream. But when the new site proved too inconvenient to river traffic on the Mississippi, it was moved again, this time closer to the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers.

Always tenacious, Arkansas Post survived as a small but strategic French outpost. It served as a military station as well as a hunting village but was still vulnerable to flooding. And so, after the Spanish took control of Louisiana in 1763 with the end of the French and Indian War, they moved it back to Ecores Rouges, thirty-six miles from the mouth of the Arkansas.3 After the American Revolution, settlers began to slowly cross the Mississippi into French Louisiana. Arkansas Post saw very few of these Americans, but it was still the only settled village in the region. Even the Indian population had been drastically reduced due mainly to disease, alcoholism, and tribal warfare. So by the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 this tiny colony, now numbering about 150 people, was the only one available as a foothold—and a name—for the land between Illinois Country and New Orleans.

Post-Purchase

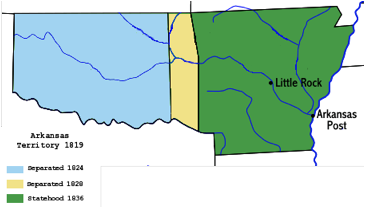

After the United States paid France for their claim to a vast and mostly borderless region in the middle of the continent, the areas west of and adjacent to the Mississippi River were the first to be settled, organized and named. In 1804 the vast region was divided at the 33rd parallel, creating what would become Arkansas’ southern border. South of the line was the Territory of Orleans; north was the District of Louisiana. The following year, the District became the Territory of Louisiana, and itssouthernmost district was named New Madrid and included the settlement of Arkansas Post.

All this time settlers were beginning to file in to northern Arkansas, migrating south from St. Louis, the capital of Louisiana Territory. In 1806 a “District of Arkansas” was created; then in 1807 it was eliminated, and in 1808, re-created4 in order to govern the growing population. In 1812 the Territory of Louisiana became Missouri Territory, and Arkansas was quickly made a southern county.

In February of 1819 it was proposed in Congress that “the Arkansas country” be officially divided from Missouri and made a separate territory. The ensuing debate was a continuation of the heated arguments surrounding slavery and its future in any new territories, and so almost no attention was paid to the name proposed. In fact, during the arguments “Arkansas” was referred to (with its modern spelling) as if it already existed as a territory in order to further the conversation regarding slavery. The following month, without yet acting on the Missouri statehood question, Arkansas was indeed separated and made a U.S. Territory, albeit with wider boundaries than it has today.

Statehood and the Name

The first newspaper of the region was the Arkansas Gazette , which did much to standardize the spelling of the state’s name, both by adopting it as its title and by appealing fervently for statehood between 1819 and 1836. Statehood was granted to Arkansas on June 15, 1836, with the signature of President Andrew Jackson, but the most famous deliberation concerning the name of the 25th state was yet to come.

No doubt, the spelling and pronunciation of Arkansas are firmly embedded in the linguistic history of the region, with its Indian and French origins. One Arkansas historian, Judge U. M. Rose, noted that the final “s” was added in the earliest French writings to make plural the name of the river and the natives—in order to create such phrases as “les pays des Arkansas” and “la riviere des Arkansas.” He claims that even in 1803, when the region was ceded to the U.S., the issue of the final “s” was still unsettled.5 Rose’s research indicates that the current pronunciation of the word, as if it were spelled “Arkansaw,” is consistent with that of its Indian heritage and that any pronunciation with the accent on the second syllable (as if pronouncing “Kansas” with an “Ark-” prefix) was considered an innovation around 1836 when the territory achieved statehood.

Legendary, however, is the story of two Congressmen, shortly after statehood, who could not agree between these two pronunciations, one insisting on being introduced as a representative of “AR-kan-SAW,” and the other just as adamant that he was from “Ar-KAN-sas.” Legendary too, and just as difficult to trace historically, is the account of Cassius M. Johnson, a fictitious Arkansas congressman who was said to have delivered a fiery, and according to most versions, vulgar speech entitled “Change the Name of Arkansas?! Hell No!” The Johnson story is said to have been related orally as early as the 1880’s but has been published with varying degrees of profanity several times since. Here’s an excerpt from one of the more sanitized versions:

And now comes this pusillanimous, blue-bellied Yankee who wants to change the name of Arkansas. Why, Mr. Speaker, he compares the great state of Arkansas to KANSAS! You might as well liken the noonday sun in all its glory to the feeble glow of a lightning-bug’s ass, or the fragrance of an American Beauty rose to the foul quintessence of a Mexican burro’s fart!6

This version of the speech has been reproduced several times on the Internet, once with an excellent history of the legend written by Michael Simmons, who asserts that the original was likely written by Mark Twain.

What is verifiable is that in 1881 the Arkansas State General Assembly passed a resolution determining the official pronunciation of the state’s name, as well as its correct spelling. Though there are those who claim whimsically that this law made it illegal to mispronounce Arkansas, the resolution was not exactly binding. As state-name historian George Shankle describes, the law rather “specifies that the first and last syllables of the word shall carry the accents, and that the pronunciation with the accent on the second syllable with the ain this syllable sounding short as it does in the word man, and sounding the final s, is to be discouraged.”

Clear enough? Well, consider this. The law does not specify what people from Arkansas are to be called. Those who resent any connection to Kansas refer to themselves as “Arkansawyers.” Others prefer “Arkansans,” which is more commonly used, but is difficult to pronounce in accordance with the aforementioned law.