ARIZONA

Arizona take off your rainbow shades

Arizona have another look at the world

…

Arizona cut off your Indian braids

Arizona hey won’tcha go my way

—Mark Lindsay, Arizona

“If you can find lower prices anywhere, my name ain’t Nathan Arizona.”

—From the film, Raising Arizona

Deserts

A desert, any dictionary worth its weight in sand will tell you, is a barren ecosystem that receives less than 250 millimeters of rainfall annually. The label is bestowed upon many places in the U.S., some more deserving than others. The central plains states, currently productive farmland, were referred to as “The Great American Desert” for much of the 1800s because of the lack of trees and hills. The appellation is still used today, albeit nostalgically. Perhaps the most famous deserts in the nation are the Mojave in southern California and the Great Basin of Utah and Nevada, both deserving of the designation, as they receive less than the defining amount of rainfall per year. Some deserts are not as widely known, like the Red Desert of southwestern Wyoming and the Great Sandy Desert in southeastern Oregon. These smaller regions are often designated “deserts” to suit local purposes such as tourism or agricultural grants, but are actually parts of larger deserts.

The state name with which we tend to associate the word “desert” more than any other must be “Arizona.” In this diverse land we see petrified rocks, the Grand Canyon, Navajo and Apache Indians, towering saguaro cacti, and lots of heat and sun. We find the appropriately named city of Phoenix, rising from the sweltering ruins of the mysterious Hohokam Indians. We think of Wyatt Earp and his brothers dueling it out with the Clanton gang in another colorfully named town, Tombstone. We remember Holly Hunter and Nicholas Cage fumbling their way through crimes and misdemeanors in Tempe to care for a stolen child named Nathan Arizona. The Arizona deserts seem to be the number one choice for Hollywood’s desert-based film locales.

Yet deserts aren’t the only natural wonders of The Grand Canyon State. For starters, you can find, well, the Grand Canyon there, one of the world’s top tourist attractions and grandest natural marvels. The Kartchner Caverns were discovered in 1974 and developed into an Arizona state park in 1988—the birthing site for hundreds of myotis bats each year. And even with the minimal precipitation measurements found throughout most of the state, cities like Flagstaff boast winter attractions with an annual snowfall of 100 inches and terrain ideal for alpine and Nordic skiing. Despite the blistering arid summer temperatures contradicted by the thundering torrential downpours of the monsoon season, Arizona just might have something for everyone.

Arid Zone?

There are various strange theories about the origin of the word “Arizona,” and one of the strangest is found in Henry Gannett’s State Names, Seals, Flags, and Symbols, which claims that the word is Spanish for “arid zone.” The phrase “árida zona” is often used as a quaint, comical reference to the state, and at least one author in the early 1900s fiercely defended it as the correct origin for the name: “…others reject the obvious árida zona of the Spanish in favor of some strained etymologies from the Indian dialects, about which no two of them agree. Why should the name not have come from the Spanish, and why should it not mean just simply arid zone or belt?”1 Even though the correct Spanish would be “zona árida,” this fanciful theory of etymology hangs around to this day.

Another oft-quoted theory about the name Arizona is that it comes from an Aztec word, Arizuma, meaning “silver-bearing.” Writing in 1889 preeminent American historian Hubert Howe Bancroft dismissed this theory as “extant, founded on the native tongues, offer[ing] only the barest possibility of partial and accidental accuracy.”2

Bancroft rejects other possible derivations for the same reason:

ari , ‘maiden,’ and zon , ‘valley,’ from the Pima; ara and sunea , or urnia , ‘the sun’s beloved,’ from the Mojave; ari , ‘few,’ and zoni ‘fountains’; ari , ‘beautiful,’ and the Spanish zona ;… Arezuma , an Aztec queen; Arizunna , ‘the beautiful;’ Arizonia , the maiden queen or goddess who by immaculate conception gave being to the Zuñi Indians3

Indeed the story of the naming of Arizona must reach back into the history of what is now the region of the international border between Arizona and Mexico’s state of Sonora.

The Real de Arizonac (or just Arizonac) was a ranchería (village) in the area south of modern Tucson, and is the undisputed source of the name Arizona. But how did a tiny mining village that existed for less than two decades, and was then cleanly wiped from the map, come to be elevated to the rank of U.S. state name? The events were indeed circuitous, winding through San Francisco and Washington D.C., and the outcome was never certain.

The Silver of Arizonac

It is believed that Arizonac was founded in 1730 by a Spanish Captain named Gabriel de Prudhon who served as Alcalde Mayor of Sonora from 1727 until 1733. In 1733 he published a map of northern Sonora, which included “Arizonac”, one of several mining towns in the area.

In 1736 a Yaqui Indian named Antonio Sirumea discovered some large chunks of silver in a small arroyo just north of Real de Arizonac. Word of the find spread, and prospectors flocked to the region. While mineral strikes in Sonora were not uncommon, this one became legendary, in part because of the nature of the ore. The silver appeared very pure, almost refined, and was found in large nuggets that averaged twenty-five to fifty pounds. Also found were slabs, or planchas , of silver, some weighing hundreds and even thousands of pounds, which could only be moved with great difficulty, usually by breaking them into smaller pieces. Some of the miners dug the ground in search of a vein, but in every case the silver went no further than about sixteen inches under the surface.

Historians speculate that what these miners found was horn silver (cerargyrite, or chloride of silver) which can form when hot water containing a type of silver in solution meets a shallow pool of salt water. When subjected to volcanic heat, it can harden into slabs or plates.

When Spanish officials learned of the find, they sent Juan Bautista de Anza, commander of the presidio at nearby Santa Rosa de Corodéguachi (Fronteras), to investigate. The contentious issue was whether the remarkably pure silver nuggets constituted natural ore that had been “mined,” in which case the king would receive twenty percent—a quinto—or whether it was buried treasure which had been “found,” which would allot the king half. The finder would keep the other half, minus a quinto for weighing, assaying, and stamping.

When de Anza arrived at Arizonac and was shown the site of the silver find, no more ore was left, nor were any of the prospectors. The region was Apache territory, and once the silver was exhausted and the Indians began to gather, the miners fled with their riches into the nearby towns. De Anza ordered a thorough investigation and demanded that all of the silver be confiscated. Angry residents and merchants of the region began to petition for the return of their silver, but the legal battle would drag on for years. Finally, in 1741, King Philip V of Spain declared the silver his own and levied judgments against some of the Sonoran merchants for defrauding him of duties on his treasure.

The value of the silver found at Arizonac in 1736 was not historically significant. But the litigation and controversy surrounding it made it famous, and accounts of the events written in the decades following the king’s decree declared the silver “fabulous,” “incredible,” “a sight never before seen.” In at least two of these accounts, the name of the mining village is written “Real de Arizona,” dropping the final “c.”

Mining resumed in the region of Real de Arizonac in 1754 but only briefly. The remoteness of the region, the expense of bringing in equipment and provisions, as well as shipping the ore out, and the hostility of the Apaches proved the effort too expensive, and for the next century the region was virtually deserted.

Papago orBasque?

In the 1960 edition of Will C. Barnes’ Arizona Place Names, it is claimed that the word “Arizonac” derives from the Papago Indian words ali (“small”) and shonak (“place of the spring”). Barnes goes on to quote James H. McClintock, another state historian, who claims that the Spanish dropped the final “c” to adapt the word to Spanish phonetics. This “Papago theory” of derivation has been widely accepted as correct, but there is another possible etymology for the word.

In 1979 William A. Douglass published a paper in the periodical Names , which sets forth convincing evidence that the word Arizonais actually derived from the Basque dialect of Northern Spain. Douglass asserts that the aforementioned McClintock cut short the research on the history of the state’s name by declaring the Papago theory to be correct in 1916 and discouraging further research. Douglass’ own research does not discount the Papago theory but offers thorough arguments that suggest the word originated in the Basque (a region in northern Spain) language as either arritza-ona , “the good (or valuable) rocky place,” or aritza ona , “the good (or valuable) oak.”

He cites the map created in 1733 by Gabriel de Prudhon—who was of Basque descent—in which Prudhon labels “Real de Arizonac” and names himself founder of the tiny mining village. Douglass accounts for the final “c” by noting that it is a Basque pluralizer. Finally, Douglass justifies his proposed definitions by explaining the importance of oak in the Basque culture—and the prominence of oak trees in northern Sonora—as well as the prevalence of the Basque ethnicity among Spanish explorers of the region where the silver was found.4

The name “Arizona” was applied to the nearby mountains and to a small arroyo near the ranchería and would continue to appear on maps as such, even after the mines were abandoned. But the actual location of the ranchería once called “Real de Arizonac,” or of the site where the silver was found, is not known today. Researchers point to the fact that the operation was so brief, and the mines so shallow, that any infrastructure could easily have degraded to almost nothing over the decades of abandonment. Also, again because of the brevity of the town’s existence, no formal government was ever established, no surveying accomplished, and no detailed maps generated.

Gadsden and Santa Anna

From about 1750 until 1848, Nuevo Mexico (modern New Mexico and Arizona, as well as much of northern Mexico) reverted to a sparsely populated region of small pueblos, poor missions, and belligerent Indians generally ignored by the rest of the world, even by its own Spanish, and later Mexican, government. According to Arizona historian Rufus K. Wyllys,

“The reasons for this obscurity of Pimería Alta…largely centered around the Apache Indians, but the breakdown of the efforts to bind California to Sonora and New Mexico caused the viceroys to neglect the Pima country and leave it to look out for itself.”5

During this period “Arizona,” “Real de Arizona,” and “District of Arizona,” described a vague area of New Mexico surrounding the old ranchería in the vicinity of what would more famously become the territory of the Gadsden Purchase.

Then, in 1848 distinct borders for Arizona began to take shape with the signing of theTreaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War. The terms of Mexico’s surrender involved ceding to the U.S. any claims on Texas as well as the New Mexico Territory north of the Gila River and all of Alta California. The war and the treaty were controversial in Mexico and the U.S. Mexicans were angered at the loss of so much territory, and some Americans felt that the U.S. had taken unfair advantage of their southern neighbor at a time when Mexico was struggling to maintain its independence from Spain. Nevertheless, the deal was done, and many Mexicans—once Spaniards—now found themselves American citizens.

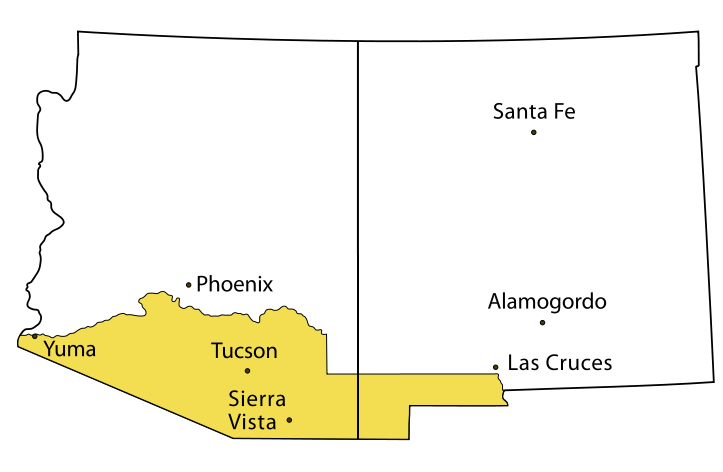

Shortly after the war, a group of railroad men, including one James Gadsden, determined that the most direct route for a southern railroad line to connect the southeastern U.S. to the Pacific Coast lay just south of the new border with Mexico. Conveniently, a survey of the area had been riddled with mistakes, and the actual border was still under dispute. In 1852 and 1853 Gadsden negotiated the Treaty of Mesilla with Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna and obtained almost thirty thousand acres for ten million dollars in order to obtain the needed land for the train route. Historically better known as the Gadsden Purchase, it too was unpopular in both countries and contributed to the downfall of Santa Anna’s dictatorship of Mexico. The region purchased was south of the Gila River and contained the fertile Mesilla valley and the city of Tucson but did not contain the region of the ranchería of Arizona, which still lay just south of the border. While today the specific location of the small village that lent its name to our 48th state is not known, it is generally agreed that “Arizona” is not in Arizona, but in Mexico.

The Father of Arizona

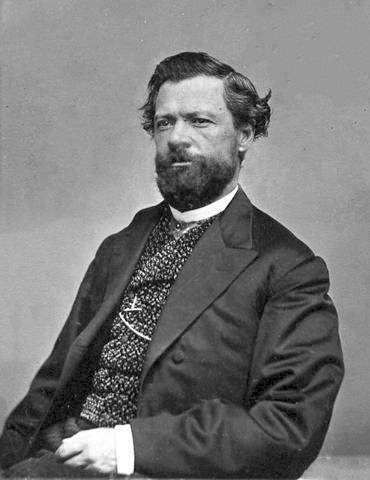

Enter Charles D. Poston, widely referred to as the “Father of Arizona,” though it is probable that he applied the nickname himself. Poston was a native of Kentucky who was working as a customs clerk in San Francisco during the gold rush of the early 1850s. He lived at the “government boarding house,” so called because of the large number of state and federal officials who also resided there, where he and his friends would sit and talk nightly over bottles of brandy of the possibilities for exploration in the newly acquired territory of New Mexico.

Poston and his fellow boarders were intrigued by the appearance in San Francisco of an attorney representing the family of the former Mexican emperor Don Augustin de Iturbide. Iturbide was declared “Emperor” of Mexico in 1822 after that nation had won its independence from Spain. His reign, however, lasted only eight months until he was overthrown and executed by revolutionaries led by Santa Anna. The attorney who arrived in San Francisco had with him a legal land grant from the Mexican government for millions of acres of land in northern Sonora which had been given to the Iturbide family as an indemnity after the emperor’s death. As the heirs’ representative, he was offering incentives for land speculators to go and find the grant in Sonora and begin colonization.

According to Poston, “Old Spanish history was ransacked for information, from the voyages of Cortés in the Gulf of California to the latest dates, and maps of the country were in great demand.” One book that was probably consulted was Noticias Estadisticas del Estado de Sonora , etc.,by José Francisco Velasco. Published a few years earlier in 1850 in Mexico, it contained exciting reports of the mineral wealth to be had with ease in the northern Sonora region, and it refers specifically to “Arizona,” describing the pure silver found there a century earlier and the controversy that it sparked.

From Velasco as well as other sources, the prospectors in San Francisco learned that

“ ...the State of Sonora was one of the richest of Mexico in silver, copper, gold, coal, and other minerals, with highly productive agricultural valleys in the temperate zone. That the country north of Sonora, called in the Spanish history “Arizunea,” (rocky country) was full of minerals, with fertile valleys washed by numerous rivers, and covered by forests primeval.”6

Poston quoted these sources in this excerpt from a magazine article in 1894, well after his years in Arizona and after its formation into a territory, but no explanation is given for the unique spelling of the name, “Arizunea” or of his brief definition, “rocky country.”

What is clear is that Poston’s life would be forever changed by the information he gleaned while in San Francisco. In 1854 he made his first reconnaissance mission to the area and founded the township of Colorado City which would later become “Arizona City” and still later “Yuma.”7 During this first trip Poston became enchanted with the region, writing later, “The country...is the most marvelous in the United States.” He was also impressed with the Pima Indians who lived there, gushing that they had “...many features worthy of imitation by more civilized people.”

The following year he went to New York and gathered support and funding for a new company which he called the “Sonora Exploring and Mining Company,” of which he was manager and commandant. In 1856 he returned to New Mexico and set up his mining operations at the old Spanish presidio of Tubac, just a few miles south of the relatively large village of Tucson.

For the next four years, Poston oversaw the operations of the silver mines in Arizona and acted as a de facto governor for the region, referring to himself as Alcalde (Spanish for “mayor”) of Tubac. Under his stewardship, this community of mostly Mexicans and Pima and Papago Indians enjoyed relative peace with the Apaches. They formed their own currency and saw the beginning of the first local newspaper, the Arizonian. It was common knowledge that the actual territorial government located in Santa Fe was too remote and too disinterested in the affairs of Arizona to be of any consequence to its inhabitants, and Poston’s mines were easily the largest legitimate employer for miles. So while he enjoyed some power, he seems to have ruled with a judicious hand. He even performed marriage ceremonies and wrote with pride of his many godchildren named “Carlos” or “Carlotta.”8

Virtually everyone involved in New Mexico, which at that time consisted roughly of the current states of New Mexico and Arizona, wished to amputate the western section of the territory. As early as 1854 authorities in Santa Fe who were reluctant to take on the problem of the Apaches in the far west, petitioned Congress to create a separate territory out of the western half of New Mexico. They even proposed names: Pimeria, one of the region’s historic names, Gadsonia, derived from Gadsden of purchase fame, and Arizona, which was becoming widely used to refer not only to the southern part of the region, but the entire western half of New Mexico. The bill was defeated in 1854, and would be resubmitted several times, always unsuccessfully.

The Confederate Arizona

The Civil War forced further change in Arizona, albeit temporarily. In June of 1861 the U.S. Army abandoned the area completely, and Poston was forced to flee as well. Without the presence of any military, it was clear that the Apaches would soon attack the mining camp, and in fact before Poston could leave, Apache marauders stole all of the company’s horses, making his departure not only necessary but difficult.

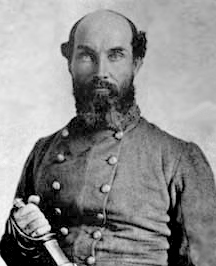

On July 23, 1861, Confederate troops led by Lieutenant Colonel John R. Baylor seized Fort Fillmore in the southern Mesilla Valley of New Mexico. This area was populated mostly by farmers who had moved there from Texas and therefore tended to ally themselves with the southern cause. On August 1, Baylor declared the southern half of New Mexico, all that land below the 34th parallel to the Mexican border and stretching all the way to California, to be the new Confederate Territory of Arizona with himself as governor.

After the Union victory at Glorieta near Santa Fe—a grisly two-day battle that has been given the poetic label “Gettysburg of the West”—the Confederate troops retreated to Texas, and the borders of New Mexico territory reverted to their original positions. The short-lived Confederate Territory of Arizona was of little consequence, except to point out to Congress that the region, far from being a barren wasteland, contained vast mineral wealth that could help the Union cause.

But the area needed some attention. Charles Poston had gone to Washington and was engaged in an effort to divide the territory. It was during his talks with Senator Ben Wade of Ohio, Chairman of the Committee on Territories, that Wade expressed his oft-repeated description of Arizona, “O, yes, I have heard of that country—it is just like hell—all it lacks is water and good society.” Finally, Congress passed the bill creating Arizona out of the region of New Mexico west of the 111th degree of longitude west and in February, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed it. Poston was named Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the new territory and later would be its first elected delegate to Congress.

Like New Mexico, with which its fortunes were perpetually linked, statehood was elusive for Arizona. Congress was rife with prejudice against the Mexican and Indian populations of the area and rejected proposals for statehood for almost fifty years. In 1902, the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, Albert Beveridge of Indiana, a particularly outspoken bigot toward the indigenous populations of the southwest, proposed recombining the two territories with the name “Arizona the Great.” His motive was to dilute the Indian and Mexican populations of New Mexico with the now Anglo majority in Arizona.9 Arizona’s Anglo population had grown substantially during the half-century of territorial status. White prospectors came to mine, and white railroad men and ranchers flocked to the area, once the Apache threat was mitigated by the presence of new federal forts and troops. The jointure project, however, was defeated, and the struggle for statehood continued.

Finally on February 14, 1912, only weeks after New Mexico achieved statehood, Arizona was proclaimed the 48th state of the U.S., completing the puzzle of the continental United States of America. One Arizona historian notes, “There was rejoicing by flagmakers.”10

End Notes

1. Van Dyke , John C., The Desert: Further Studies in Natural Appearances (New York, 1903), p. 208n.

2. Bancroft , Hubert Howe, The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. Vol. 17: History of Arizona and New Mexico , 1530-1888 (San Francisco, 1889), pp. 520-521.

3. Ibid., p. 521[fn].

4. Douglass, William A., “On the Naming of Arizona,” Names , December, 1979, pp. 217-234.

5. Wyllys, Rufus Kay, Arizona: The History of a Frontier State (Phoenix, 1950), p. 60.

6. Poston, Charles D., “Building a State in Apache Land”, Overland Monthly , July, 1894, p. 88.

7. Gressinger, A.W., Charles D. Poston: Sunland Seer , (Globe, Arizona, 1961), p. 18.

8. Overland Monthly , Aug., 1994, p. 208.

9. Powell, Lawrence Clark, Arizona: A Bicentennial History (New York, 1976), pp. 60-61.

10. Powell, p. 62.