ALASKA

Baked Alaska

1 8-inch round cake

1/2 gallon of ice cream

5 egg whites

1/2 tsp. cream of tartar

2/3 cup of sugar

Place cake on cookie sheet. Form softened ice cream into an igloo shape on top of cake. Trim cake to within 3/4” of the ice cream. Refreeze cake and ice cream. Preheat oven to 450º. Whip egg whites until they form stiff peaks. Gradually add cream of tartar and sugar. Spread meringue over “igloo” till ice cream is completely covered. Bake for 3 minutes. Serve immediately.

North to Alaska! Go North, the rush is on…

— Johnny Horton, North to Alaska

Frozen but Fascinating

Alaska is the only U.S. state with which words like “Arctic” and “frozen tundra” can be readily associated. And since the 2008 presidential election, some new words are now associated with Alaska—words like “Sarah,” “Palin,” “Wasila,” and the crowd favorite, “I can see Russia from my house.” The name Alaska conveys images not only of ice and snow but of a wild frontier, unspoiled by humans, the last of its kind in the nation.

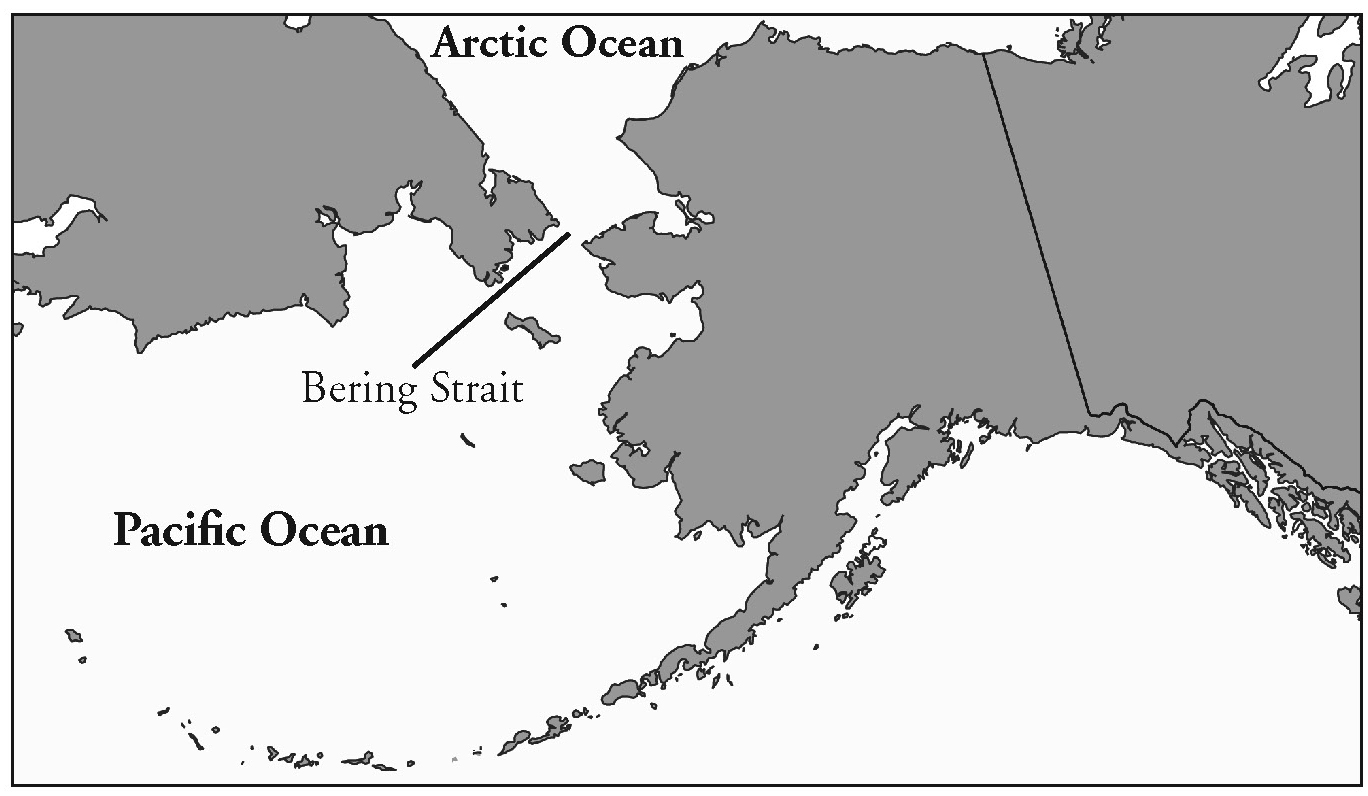

More and more, Americans have learned to embrace the diversity, not to mention the shear breadth, of our largest state. Its hundreds of islands stretch into the eastern hemisphere and southward to the same latitude as London, and its northern boundary reaches deep into the Arctic Circle. Alaska contains twice the landmass of the state of Texas. On a map of the lower forty-eight states overlaid with a map of Alaska, the edges of the state reach from Atlanta to San Francisco, from Green Bay to Tucson. It’s big.

Controversy over drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge has introduced many Americans to this pristine land. The debate, which has raged for decades, has polarized the nation over concern for a land that the vast majority have never seen, never been anywhere near, nor are likely to be. Indeed, the closest many of us have gotten to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is watching “Ice Road Truckers” on the History Channel. But then, that is the point. To many Americans, Alaska is our last chance to leave nature alone on a scale that is no longer possible in the lower forty-eight.

But that doesn’t stop us from fantasizing about, even glamorizing, an existence in the United States’ own chunk of the Great White North. Movies like John Wayne’s North to Alaska and the wildly successful TV show Northern Exposure exposed (pardon the pun) the love affair Americans have with Alaska, while at the same time demystifying what, to most people, is a rather mysterious place. Intellectually we know that in Alaska the sun hardly sets in the middle of summer, and barely rises in the dead of winter. We know that Alaska is the coldest place (and, incidentally, the least warm place, which is to say its average high temperature is lower than that of any other state) in the nation. We understand that it is separated from the rest of the country by a boat ride, a plane ride, or a very long road trip through Canada. Still, we ask ourselves…wouldn’t it be cool to live in Alaska?

Bering vs. Columbus

A comparison of the North American explorers Christopher Columbus and Vitus Bering is striking not only for the similarities it reveals but also for the extreme differences. Columbus was not a Spaniard but an Italian sailing for the Spanish monarchs in 1492. Vitus Bering was not a Russian but a Dane in the employ of Czar Peter I of Russia. In 1725 Peter instructed Bering to go to Kamchatka, a peninsula in eastern Siberia and from there to sail “along the land which goes to the north, and according to expectations (because its end is not known) that land, it appears, is part of America.” He further ordered Bering…

“to search for that [place] where it is joined with America, and to go to any city of European possession, or if you see any European vessel, to find out from it what the coast is called and to write it down, and to go ashore yourself and obtain first-hand information, and, placing it on a map, to return here.1”

Clearly the name of the land, according to those who inhabited it, was of great importance to Czar Peter. Columbus had no such instructions from his benefactors and, just as clearly, cared not at all how the natives referred to their own land.

Unlike Christopher Columbus, who was looking for—and expected to find—a water passage to the Orient but found instead land in his path, Bering expected to see land always to the north, but instead found the strait that now bears his name. But like Columbus’ accomplishment it turns out that Bering’s discovery had already been made. Few doubt Lief Ericson’s journey to North America five hundred years before Columbus; likewise, it is now commonly held that a Cossack sailor named Semen Dezhnev sailed through the Bering Strait in 1648, almost eighty years before Bering. By the time of the Czar’s order to Bering, however, Dezhnev’s report had either not been received in St. Petersburg or had been altered dramatically so as not to be believed. A port city along the strait now bears Dezhnev’s name, at least in a small way acknowledging his feat.

Like those of Columbus, Bering’s “discoveries,” while not considered entirely successful in their day (neither, for example, has the honor of having a U.S. state named for them), were important because of the new exploration they spawned. Among their contemporaries they had indeed made great discoveries. Columbus returned to Portugal with gold for his benefactors; Bering returned to St. Petersburg with furs for his. Columbus and his successors brutally enslaved the natives of the Caribbean Islands in their unquenchable search for treasure; Bering’s successors—mostly Siberian hunters called promyshleniki —brutally enslaved the Aleutian natives in their quest for furs, almost totally destroying the population of sea otters, not to mention Aleutian natives, in the process.

The Islands

The promyshleniki were not settlers. They sailed their primitive boats to the Aleutian Islands during hunting season, lived among the natives whom they forced to do the hunting, and returned to Siberia to sell their pelts. This cycle continued for decades.

Many Alaskan history books make no mention of Stephan Glotov, one of the promyshleniki, but he is widely credited among those that do include him with determining the name by which the Aleutians referred to the mainland. Venturing further than his colleagues in the mid 1700s, Glotov explored several of the larger Aleutian Islands, including Kodiak and Unimak. While on Unimak Island in 1759, Glotov heard the natives use a specific word to describe the mainland. That word is today often written “alaxsxaq,” or something similar, but its contemporary pronunciation is subject to debate. The Russians pronounced it something like “alyashka.”

The Russians, in the person of Mikhail Gvozdev, had actually reached the mainland fifteen years earlier than Glotov, but since their focus was on the fur trade, and the fur trade existed in the islands, the “discovery” of the Alaska mainland was considered a relatively minor accomplishment. The word Alaska (which the spelling eventually evolved to) would later be translated as “object toward which the sea flows,” and once reported by Glotov, would be used continually by the Russian hunters and traders to refer to the mainland.

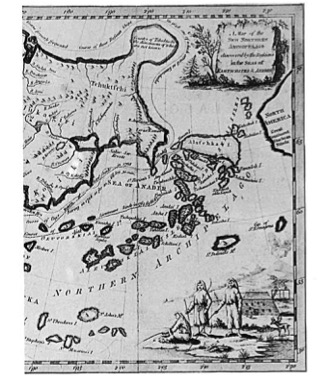

Maps of the region were typically inaccurate, drawn in St. Petersburg by cartographers using second- or third-hand information. When Captain James Cook made his third and final voyage beginning in 1776, attempting to determine once and for all the existence—or absence—of a northwest passage, he used as one of his most trusted guides what he called a “very accurate little map,” drawn by Jacob von Stählin, secretary of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The map, as Cook would learn, was not so accurate after all. As one historian asserts, it “looks as if some large fist has come down on the fragile surface of [former Russian historiographer Gerhard Friedrich] Müller’s north-west American peninsula, shattered it into displaced fragments and sent some of it into thin air.” Stählin drew “Alaschka” not as the mainland but as the largest island in what is labeled the “Northern Archipelago.”

The mainland, which appears as a mere nub on the western coast of Canada, is labeled three different ways: “North America,” “Great Continent,” and “Stachtan Nitada.” Cook was immensely frustrated when he determined that “Alaschka” was, in fact, the mainland and that “the Indians and the Russians call the whole by that name…” In his journal he railed against Stählin for publishing “so erroneous a Map2.”Cook’s second in command, Captain Clerke, also wrote of the mistakes by Stählin: “…both Russians and Indians call the Continent of America, Alaschka, and are altogether Strangers to the Appellation of Stachtan Nitada which it is called by Mr. Stählin.3” J.C. Beaglehole, editor of a 1967 compilation of Cook’s journals, concludes that the phrase Stachtan Nitada “seems to be quite meaningless.”4

Russia finally got around to settling parts of the Aleutian Islands in 1784, when a businessman named Gregor Shelikov started a colony at Three Saints Bay on Kodiak Island. Despite Spain’s half-hearted challenges to the Russian claim for what they called “Florida Blanca,” or “Land of White Blossoms,” the world soon, and peacefully, began to acknowledge the land as Russian, and Alaska started appearing on maps as “Russian America.”

The name “Alaska” was used to refer to the region also, but it usually appeared in the form “Alaskan peninsula” to describe the land that juts out from the continent without any distinct borders or any political connotations. The Russians called it “the colonies” or “our holdings in America,” and managed it poorly. The natives continued to be brutalized, and the wildlife continued to be hunted and fished to near-extinction.

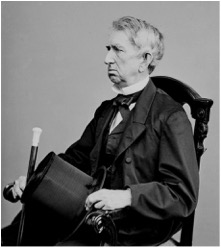

Seward and Sumner

In 1867 President Andrew Johnson, along with the Secretary of State William Seward, finalized a deal with Baron de Stoeckl of Russia for the purchase of Russian America for $7,200,000. Although the region came to be known by such comical epithets as “Seward’s Folly,” “Seward’s Icebox,” “Icebergia,” and “Walrussia” in newspapers of the day, the purchase of Russian America was not as unpopular as some history books maintain. Even while some newspapers were lampooning the purchase on their cartoon page, they were applauding it in their editorials. Still, while Americans were not acrimonious concerning the purchase of a northern wilderness, they had little notion of why it was acquired or what to do with it.

Charles Sumner, Senator from Massachusetts, proposed the purchase in Congress. His speech to the Senate lasted three hours and takes up eighty dense pages in the Congressional Record. He described in detail Alaska’s history, natives, natural resources, geography, and any other information he had gleaned on the territory. Near the end of the speech, Sumner had this to say about what to call the new acquisition:

“As these extensive possessions, constituting a corner of the continent, pass from the imperial government of Russia they will naturally receive a new name. They will be no longer Russian America. How shall they be called? Clearly any name borrowed from classical history or from individual invention will be little better than a misnomer or a nickname unworthy of such an occasion. Even if taken from our own history it will be of doubtful taste. The name should come from the country itself. It should be indigenous, aboriginal, one of the autochthons [earliest known inhabitants] of the soil...”

Sumner did not think of this notion on his own. The 1850s and 60s were big decades for territory- and state-making, and the use of aboriginal names was quite in fashion. Sumner would have known of the recent proposals of names such as Kansas, Nebraska, Dakota, Wyoming, and Utah. He continued…

“…Happily such a name exists, which is as proper in sound as in origin. It appears from the report of Cook, the illustrious navigator, to whom I have so often referred, that the euphonious name now applied to the peninsula which is the continental link of the Aleutian chain was the sole word used originally by the native islanders, ‘when speaking of the American continent in general, which they knew perfectly well to be a great land.’ It only remains that, following these natives, whose places are now ours, we, too, should call this ‘great land’ Alaska5.”

Eloquent as Sumner’s speech was, it perpetuated a myth that had developed surrounding the name “Alaska.” The meaning of the word had been widely reported as “great land” which was, in fact, a phrase lifted directly from Cook’s journal. But the evolution of the definition of “Alaska” probably skewed this translation to some extent. “Great” had most likely meant “big” or “large” when originally translated but took on the connotations of “wonderful” and “magnificent” for those English speakers who found it convenient or useful.

geography and common sense.”

The U.S. established a military government in Alaska for the first seventeen years following the purchase, during which time the U.S. Navy was in charge. Finally, in 1884, the Organic Act of Alaska organized the region as a District and provided for the installation of government agencies including courts and schools. Unfortunately many of the first government appointees in Alaska were incompetent and/or unethical, and the situation of most residents was made worse instead of better. Alaskans, becoming increasingly frustrated, actually offered in 1890 to repurchase their homeland for twice the sum that the U.S. had paid to Russia.7 The proposition, while rejected, got the attention of the U.S. government who now knew that Alaskans were serious about official organization. Congress began, albeit slowly, to pay more attention to the process of bringing Alaska into the statehood fold.

A National Treasure

Even before it became a territory, the valuable natural resources of Alaska caused endless political disputes, both domestic and international. The discovery of gold near Fairbanks in 1902 touched off one of many boundary disputes, this one between the U.S. and Canada. A compromise between the two countries determined the current position of the line that meanders from the 141st parallel at Mount St. Elias (named by Vitus Bering for the holy day on which he first saw the peak) to the Dixon Entrance, or southeastern tip of the state.

The investments in mining also increased the opportunities for other industries in Alaska, such as railroads and the timber and fishing industries, many of them controlled by an “Alaskan Syndicate” which included the Guggenheim family and J. P. Morgan. The rapid development of all of these industries increased the possibilities for fraud and corruption.

A famous dispute was touched off in the Taft administration in 1909 involving Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger and Gifford Pinchot, who served in the Department of Agriculture as head of the Forestry Service. Pinchot had been appointed by Taft’s predecessor, Teddy Roosevelt, and agreed strongly with Roosevelt’s policy of land conservation and wilderness preservation. Ballinger was more sympathetic to the mining and business interests in Alaska and used his power to return to the public domain and make available for sale several million acres of Alaskan land that Pinchot had previously set aside as ranger stations. Perhaps in retaliation, Pinchot strongly supported a colleague who publicly accused Ballinger of improperly issuing some Alaska coal mining claims. Ballinger was cleared of any wrongdoing in a congressional investigation, but the public debate had far-reaching effects. Taft and Roosevelt, formerly allies, became political rivals and split the Republican Party, allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the next presidential election.

In 1912, after several Supreme Court decisions and constitutional challenges, and with the passage of the Second Organic Act, Alaska was transformed from a District to a Territory with a guarantee of eventual statehood, and yet that status was still more than half a century away. The Depression and World War II delayed many domestic matters, including the statehood issue for Alaska and Hawaii.

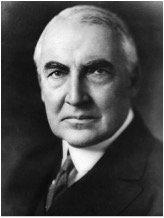

While Alaska waited for statehood to be conferred, there existed separatist movements in the Alaska Territory, some of which would have divided the state into as many as five separate states. Among these was a strong push by the population of the panhandle region—the finger of coastline that runs from the 141st meridian to the Dixon Entrance—to separate from the rest of the territory. Their plan was to break off this most populated portion, that which included the largest city, Juneau (also to have been the name for the new territory/state) and try to achieve statehood sooner for that section. This proposal was given favorable attention by then President Warren G. Harding in 1923 when he visited Alaska for a gold spike ceremony to celebrate the opening of the Alaska Railroad. Had he not died in San Francisco on his way home from the territory, the shape of Alaska could look very different today.

On January 3, 1959, President Dwight Eisenhower finally signed the proclamation admitting Alaska to the Union as the 49th state. The fight for statehood involved many political issues, but chief among them was the concept of self-determination, or the desire by the people of Alaska to determine the fate of their state’s resources as well as their own political destiny. But even that goal would prove to be elusive. To this day, the national image of Alaska is that of a mysterious gem being fought over by millions of people who…don’t live there.

End Notes

1. Fisher, Raymond H., Bering’s Voyages: Whither and Why (Seattle, 1977), p. 23.

2. Beaglehole, J.C. ed., The Journals of Captain James Cook on his Voyages of Discovery (Cambridge, 1967), p. 456.

3. Beaglehole, ed., p. 1337.

4. Beaglehole, ed., p. lxiv.

5. “Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts, on the Cession of Russian America to the United States,” in U.S., Congress, House, House Executive Document No. 177, 40 Congress , 2 Session, p. 188.

6. Tompkins, Stuart R., “Drawing the Alaska Boundary,” Sherwood, Morgan B. (ed) Alaska and its History , (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1967), p. 83.

7. Frederick, Robert A., Alaska’s Quest for Statehood 1867-1959 , (Municipality of Anchorage, 1985), p. 7.