ALABAMA

I have a dream that one day the state of Alabama, whose governor’s lips are presently dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, will be transformed into a situation where little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers.

—Martin LutherKing, Jr.

Big wheels keep on turnin’

Carry me home to see my kin

Singin’ songs about the southland

I miss ole’ Bamy once again, and I think it’s a sin…

—Lynyrd Skynyrd, Sweet Home Alabama

Southern Comfort

The word Alabama is gentle and lyrical, like a sweet, southern belle. It’s a word that lends itself easily to the notions of southern hospitality and down-home southern comfort that characterize the southeastern states. Collectively, they call themselves “ Dixie ,” and Alabama is their self-proclaimed heart.

Alabama is a symbol of “the South,” with all its various images, those of comfort as well as those of rebellion, and the state has found a niche in popular music culture. A country music group of the 1980s named themselves for Alabama and recorded a hit song that professed their loyalty to it: “My home’s in Alabama / No matter where I lay my head / My home’s in Alabama / Southern born, and Southern bred.” Perhaps more popular, if a little less gentle, was Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama,” a song that has survived the decades and has been recorded by the likes of Mötley Crūe and Peter Gabriel.

In actuality Alabama’s heritage is anything but gentle and comfortable. If the character of a place is defined by the important events of its past, then Alabama owes its character to a legacy of racial turbulence and cultural conflict. The state could be called the nation’s conscience, serving as it has as the stage for the Civil Rights movement, that enormous struggle to wash away the stain of slavery and the years of oppression suffered by African-Americans. The 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, the 1963 murder of four young girls at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, and the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery are icons of the Civil Rights movement, and icons of Alabama.

There are, of course, other images strongly associated with Alabama, some flattering, others painful. The “Crimson Tide” of the state’s University of Alabama, and the powerful football legacy of U of A’s Paul “Bear” Bryant and his trademark hounds-tooth hat, might top the list. Non-sports fans might remember the creative genius of childhood-friends-cum-novelists Truman Capote and Harper Lee, growing up together in Monroeville in the 1930s. Some may go further back into history and call to mind massive cotton plantations worked by armies of black slaves and lorded over by genteel white families. Those who have visited Alabama might at once envision the tiny, but accessible coastline with sugar-white beaches and bird sanctuaries, or the historical covered bridges, lush state parks, and winding rivers.

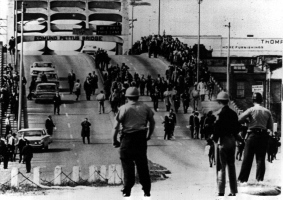

Alabama struggles not to escape but to live with its past; indeed, the sites of conflict are now tourist attractions. Not only are many of the Civil War battlefields open to tourists, so are the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and the Edmund Pettus Bridge—scene of Bloody Sunday, where the 1965 Civil Rights march to Montgomery was twice turned back.

Among the states that condoned, even embraced slavery, Alabama was one of the youngest, having inherited the practice from her parent territory Mississippi. Alabama did not invent slavery, but Alabama, with the nation looking uncomfortably on, seems to have done the most penance for it.

Culture Clashing

In 1540 Spanish conquistador Hernandode Soto led an expedition to explore La Florida. Members of his party were the first to record in writing the word “Alibamu,” “Alibamo,” or “Limamu,” among other spellings of the local tribe’s name. One of these conquistadors, known to history only as the Gentleman from Elvas, wrote of their first meeting with this native tribe:

“A few days afterward they came with him (a chief of a local tribe) accompanied by their Indians, one being named Limamu…”

Ironically de Soto, the Gentleman from Elvas, and all of the other conquistadors would later be instrumental in the annihilation of that same tribe.

The Spanish conquistadors, not generally known for their ethnic sensitivity, must have startled the Native Americans. Historian Marquis Childs describes the impression that the Spaniards must have made:

“For all their fearful suffering, one cannot help but be a little amused at the spectacle they made. They were like angry children in a rage at the sun or the moon, these gentlemen adventurers stumbling through swamp and forest with their futile armies...They were beset by fever, hunger, and the constant hostility of the Indians, whom they slaughtered and enslaved with casual cruelty.”1

By the time Hernando de Soto arrived, the natives of what are now the southeast United States knew of the cruelty that had been ministered by his predecessor, Panfilo de Narváez. Narváez proved a particularly brutal conquistador, “incompetent to the point of stupidity,”2 who ravaged tribes of the southeast coast in his brief expedition of 1528. Narváez’ expedition never traveled beyond what is now Florida, but word of his cruelty spread among the tribes of modern Georgia and Alabama. As de Soto penetrated into northern Alabama, it became apparent that the natives of the region were braced for Narváez-type cruelty.

A year and a half into his exploration of “La Florida” de Soto encountered the Indian chief Tuscaluza at his home village in modern northern Georgia or northern Alabama. Tuscaluza’s domain was large and dominated the region. His people were the Alabama Indians, a division of the Creeks who spoke a Muskhogean dialect. De Soto greeted Tuscaluza with a demand for natives to be used as slaves and concubines. Tuscaluza replied that he was unaccustomed to serving others and was in fact accustomed to being served by others; however, the chief told de Soto that a village under his domain was available with the items de Soto was requesting. It was called “Mabila”, and it was located at the southern edge of his kingdom, a few days march south along the Coosa and Alabama Rivers.

De Soto took Tuscaluza with him—part guide and part prisoner—and marched his army of 600 men to Mabila. The village was well fortified and, forewarned of the approaching Spaniards, occupied by thousands of Tuscaluza’s warriors who were bracing for a fight. When de Soto’s army arrived Tuscaluza slipped into a dwelling where he was sheltered by his people. Realizing the defiance of the natives, de Soto and his men became enraged and perhaps a bit nervous. One of the Indians was attacked with a sword, his arm severed. At that point the warriors emerged from homes with bows and arrows and began attacking the Spaniards. De Soto called for a retreat, and it appeared that Tuscaluza had turned back the powerful Spaniards, but only briefly.

De Soto would not be humiliated in this way and quickly returned to Mabila ready to defend his Christian honor against the "heathens." Spanish soldiers attacked the village with an intense fury, killing every Indian they encountered and burning every structure to the ground. The battle lasted nine hours and resulted in the near complete destruction of the tribe. A first-hand report of the battle by one of de Soto’s men declared that 11,000 natives had been killed, but modern estimates put the number nearer to 2,500. Casualties on the Spanish side were fewer: only about 20 men killed, but over 200 injured including de Soto himself.

The victory at Mabila was a hollow one for the Spaniards. The Europeans were forced to recognize that the natives of this land would not always acquiesce to their demands, no matter how much brute force was shown them—a precursor, perhaps, for the coming centuries of ethnic struggle in the region.

The Indians did not recover from their first encounter with Europeans. But while the battle with de Soto was brutal, and casualties heavy, the continued demise of the tribe, just like the destruction of tribes all over the Americas, resulted more from the diseases that Europeans brought with them. Epidemic after epidemic of smallpox, measles, and other scourges destroyed the civilization at Mabila as well as countless others. The battle, however, stood out prominently in chronicles of de Soto’s travels, and the name of the village would long be remembered. Today the exact location of Mabila is not known, but the name lives on in one of the largest and oldest port cities on the Gulf. “Mabila,” or “Mobile” as the French had it, came to refer to the place where the remnants of the tribe settled almost two centuries later.

The French

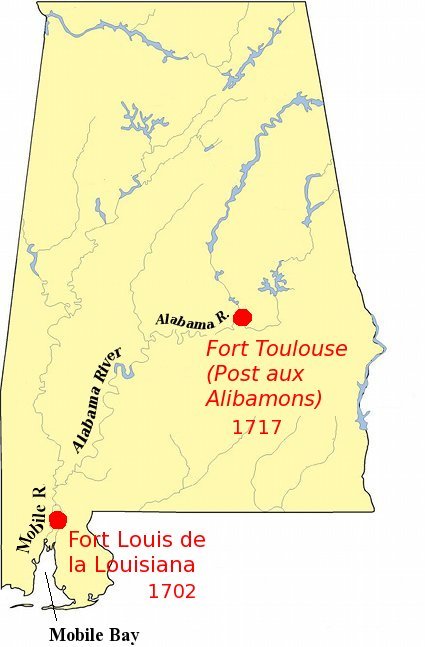

When the French explored Mobile Bay in 1702 with the hope of establishing a fort and a new French stronghold in what they now called “Louisiana,” they encountered the remaining Mobile Indians about five miles upriver from the Bay. The natives befriended them and invited them to settle in their region, hoping to gain protection from the more powerful tribes to the north. In return the natives taught the French how to farm the land, and survive in the wilderness and introduced them to tribes of the interior with whom the French wished to trade. The French called their new palisade “Fort Louis de la Louisiana” or simply “Fort St. Louis” but continued to refer to the river and the bay it empties into as “Mobile.”

Fifteen years later the natives of the interior invited the French to build another fort further north on a different river. When it was finished it was called Post aux Alibamons, or sometimes Fort des Alibamons, although on official occasions it was referred to as Fort Toulouse. The river upon which this fort was built was, naturally enough, named for the tribe who had invited the French to build it—“Alabama”. When the English in South Carolina learned of the new construction they called it that “mischievous French garrison Alebamah.3”

The British

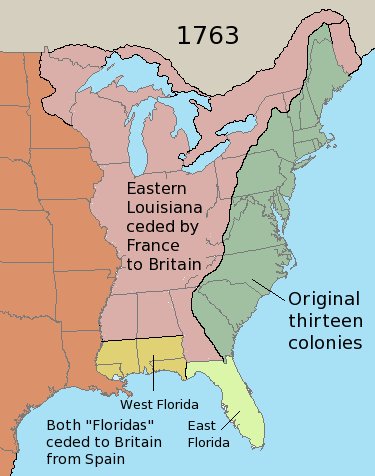

In southeastern North America the first half of the eighteenth century was marked by the struggles of the Spanish, French, and British over control of the region. Playing one against the other, the tribes of “Alabama Country” made alliances with whomever offered the most favorable trading possibilities, and they enjoyed the position of being courted for their friendship. Increasingly it was the British who won the Indians’ favor, and ultimately also won the war with France that produced the Paris Treaty of 1763. In return for peace, this treaty allowed Great Britain to receive La Florida from Spain, France’s ally, and eastern Louisiana—all the land south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi River—from France.

With the British now claiming all of North America east of the Mississippi as their own, the Indians no longer enjoyed the luxury of having two nations competing for their favor. No longer could they rely on help against enemy tribes, and no longer could they demand better trade goods from the British by comparing them with those of the French. More importantly, they began to see the prospect of their land being encroached upon and taken from them.

The native’s fears were allayed somewhat byKing George III. Almost immediately after the Paris Treaty was signed, the King forbade his subjects from moving west of the crest of the Appalachian mountain range, partly to reduce the risk of Indian wars. The colonists, who had just fought along side the British army to wrest control of that same land from the French, despised this proclamation. As colonial grumblings increased, King George’s proclamation proved to be a launching pad for revolution.

At Mobile the French handed over Fort St. Louis, and the English promptly renamed it “Fort Charlotte” in honor of the Queen, wife of George III. Fort Toulouse was handed over as well, and many of the French traders moved west to New Orleans rather than pledge their allegiance to Great Britain. Gradually their Indian friends followed them and eventually settled in what is now East Texas. By 1780 virtually the entire tribe of Alabama Indians had migrated west. And so it was that by the time the United States came into existence, the region that would become Alabama was no longer home to the Alabama Indians.

The Americans

In 1780, during the American Revolution, the Spanish, who fought on the side of the colonists, took the opportunity to regain their earlier loss. They laid siege to Mobile and won Fort Charlotte back from the British. When the 1783 Paris Treaty was signed signaling the end of the American Revolution, Spain was allowed to keep Mobile and the rest of Florida (all of present-day Florida and a thin strip of coastline to its west, all the way to and including New Orleans).

In 1803 the U.S. claimed that the Mobile District of what was then called West Florida was included in the Louisiana Purchase and in 1812 officially annexed it. Spain, however, had occupied the district for years and protested the annexation diplomatically. When the War of 1812 broke out between the U.S. and Britain, the U.S. accused the Spanish—somewhat speciously—of aiding the British, and in 1813 General James Wilkinson marched 600 troops into Mobile and demanded the surrender of the city from the Spanish Commandant Cayetano Perez. Because no declaration of war between the two countries was in place, Perez was surprised by the attack and unprepared to repel the American forces, so had no choice but to hand over the district to Wilkinson. While the surrender of Mobile was a mere footnote to the War of 1812—a war fought primarily between the U.S. and Great Britain over trade practices and maritime policies—it represented the only land acquired by the U.S., indeed the only land that changed hands at all, as a result of the conflict.

The U.S. had now succeeded in organizing Mississippi Territory—the modern states of Mississippi and Alabama—on maps and finally removed any Spanish or British claim on the land. Now the Americans had only to wrest control from the region’s inhabitants, the Creek Indians. This was accomplished primarily by Andrew Jackson in the Creek War of 1814. The decisive Battle of Horseshoe Bend saw the annihilation of hundreds of Creek braves. The Creeks’ devastating loss to Jackson forced the surrender of their homeland to the U.S. government.

The way now paved, “Alabama Fever” gripped many easterners who flooded into what was commonly called “Alabama Country” but was still technically part of Mississippi Territory. Upon arrival, these new settlers began farming in the lush river valleys. From 1810 to 1820 the white population of Alabama Country, and eventually the state of Alabama, increased ten-fold to over 127,000 people, and that population would double in the decade to follow.4

A Mystery

On December 23, 1816, a bill was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives to establish a separate territorial government for the eastern half of Mississippi Territory. After defining a set of borders roughly identical to those of modern-day Alabama, the bill proposed that the region “constitute a separate territory, and be called ‘Mobile.’” The next month, on January 17, 1817, a similar bill was introduced in the Senate again suggesting the name “Mobile” for the proposed territory. The person who proposed the latter bill was Charles Tait, a senator from Georgia who had family in the potential new state and who had plans to move there himself.

Tait’s bill was referred to committee, amended, read again on January 20, and a third time on January 30. It passed the Senate and by all rights should then have been sent to the House of Representatives. Instead, for reasons that have never been made clear, Tait requested that the bill be sent back to a select committee on which he served. On February 4 Tait’s committee introduced a new bill in place of the one that had already passed, this one proposing a territory with the same borders but with the name “Alabama.”

In the Territorial Papers for Alabama, editor Clarence Edwin Carter provides a footnote to these proceedings:

“There are certain aspects in the evolution of this legislation which cannot now be resolved. We do not know, for example, what amendments were proposed or adopted, nor why the substitute bill was introduced. Whatever debate the various bills may have evoked has not been reported, and no relevant papers in the form of amendments and reports have been discovered. For the same reason we do not know why the House of Representatives shelved its own bill of Dec. 23, 1816.”5

Indeed, one of the “aspects” which could not be “resolved” in 1952 when the territorial papers were assembled was why the name was changed from “Mobile” to “Alabama.” Both names had been used to describe the eastern portion of Mississippi Territory for many years, and either would have been appropriate. But the name change is completely ignored in history books, and so the change must remain a mystery. “Alabama” became the name of the new territory. Less than three years later, on December 14, 1819, President James Monroe signed the legislation admitting Alabama as the 22nd state of the Union.

The Alabamas

For a time it was generally (and erroneously) believed that the word Alabama meant “Here we rest.” According to the Alabama Department of History and Archives this translation was put forth in an unsigned newspaper article in 1842. A poet and Alabama statesman named Alexander Beauford Meek took that definition and proliferated it in his writings in the mid 1800s. Meek was popular within the state and traveled it extensively as a judge and state congressman, much of that travel by steamboat along Alabama’s meandering rivers. One of Meek’s most important works was a book entitled Romantic Passages in South Western History, published in 1857, which ends with the climactic words, “From such rude and troublous beginnings, the present prosperous population of Alabama, acquired the right to say, ‘Here we rest!’” Alabama historians have spent decades attempting to correct Meek’s mistake.

The word Alabama is actually derived from the Choctaw language, specifically the words alba —for “plants” or “weeds,”—and amo —for “to cut,” “to trim,” or “to gather.” Combined, the words translate to “those who clear the land,” or “thicket clearers.”6 The word Alibamons appeared on early French maps and labeled the river along which this tribe befriended the French in the early 1700s. The word remained on maps as the official appellation for the river, even after the tribe departed to Texas.

The Alabama Indians were known by neighboring tribes as those who cleared the dense thickets to establish their villages and farm the land. 6 In an interesting linguistic turn of events, when the Alabama Indians moved into eastern Texas, joined by their close allies the Koasati or Coushatta Indians, they settled in a region that is now commonly called the “Big Thicket.” This area near Nacogdoches, Texas on the Angelina and Neches rivers was perceived by the Spanish in the early 1800’s as too densely wooded to attempt to settle, or even to build a road through, and so they skirted its edges to the north and south. The Alabamas and Coushattas were accustomed to such dense woodlands, however, and were perfectly suited to build their new homes in it. There they settled, and there they have remained. Today the combined Alabama-Coushattas own 2,800 acres of land in the Big Thicket, which supports about half of their 1,100 tribe members.

While the Alabama Indians strive to maintain their cultural identity, their name lives on in a place where the clash and mixing of cultures is a defining theme.

End Notes

1. Childs, Marquis, Mighty Mississippi: Biography of a River (New York, 1982), pp. 3-4.

2. Severin, Timothy, Explorers of the Mississippi (New York, 1968), p. 12.

3. Jackson, Harvey H. III, Rivers of History: Life on the Coosa, Tallapoosa, Cahaba and Alabama (Tuscaloosa, 1995), p. 15.

4. Rogers, William Warren, et al, Alabama: The History of a Deep South State (Tuscaloosa, 1994), p. 54.

5. Carter, Clarence Edwin, ed., The Territorial Papers of the United States, Vol. XVIII, The Territory of Alabama 1817-1819 (Washington, 1952), p. 18t

6. William A. Read, Indian Place-Names in Alabama (Baton Rouge, 1937), p. 4.